If you’re commuting home in Los Angeles on the bus, that means waiting an average 20 minutes or more at a stop. Uber, by contrast, has an average wait time of five minutes. While the growth of ride-hailing in the city probably isn’t entirely responsible for its steep drop in bus riders, it’s a factor. So L.A.’s transit agency is in the early stages of considering another option: public transit on demand, called up via an app.

It’s not the only city thinking about the possibility of Uber-like city shuttles. Some, like Kansas City, have run trials with private companies. Others have already switched to an on-demand service for paratransit (transit for those with disabilities or the elderly) which typically uses an old-fashioned scheduling system. For cities planning a shift in services, a new simulator could help them visualize how agency-owned “microtransit” would work in their locations.

“Cities know this is necessary,” says Rahul Kumar, VP of revenue at TransLoc. “They see the success Uber and Lyft are having, but they have so many things on their plate that it’s really difficult for them to solve this problem.”

The company has an existing product that some agencies are now using to run demand-response, flexible options for safe rides, and paratransit. But the new simulator could help other cities also decide to make the shift–and analyze whether on-demand service also makes sense to replace or supplement some regular city bus routes. Because agencies use the simulator in combination with a pilot, it doesn’t have a separate cost; the simulator and a year-long pilot can cost between $10,000 and $25,000.

Dayton RTA, like some other agencies, is already partnering with a ride-hailing company–in their case, Lyft–to connect people living in more rural parts of the county with areas where buses are more frequent (during the current pilot, this service is free; other areas, like sprawling, suburban Orange County, California, partially subsidize Lyft rides). But Dayton’s work with TransLoc will begin transforming existing services that use its own vehicles.

For an older paratransit rider with unpredictable health issues, on-demand service could make it possible to get to same-day appointments; for the transit agency, it makes it less likely that rides will be canceled, helping the service run more efficiently. “We definitely [expect to] see savings through productivity,” says Policicchio. Though some riders might not have smartphones, the service will use TransLoc’s web booking platform; the same operators that currently schedule paratransit rides can manually input ride requests for those who can’t use the app.

Microtransit might also help cities make better use of buses by replacing those buses with on-demand shuttles on little-used routes, and moving buses to increase service in areas where rides are crowded. “When we look at where we’re running fixed-route services where it’s extremely low productivity, low ridership, if we can invest those service hours somewhere else, providing microtransit can be a lower-cost option, but still provide service to those areas where we pulled our fixed route,” he says.

Cities could use the new simulator to see how microtransit might be used to increase access to work for poorer neighborhoods, or access to grocery stores for food deserts, or to solve the “first mile/last mile” problem for public transportation, where people end up driving to work because they can’t easily reach a train station or other transit hub.

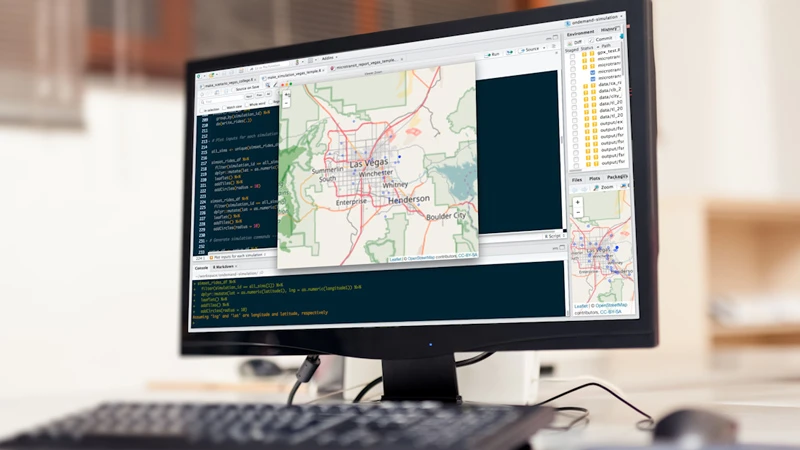

When TransLoc works with a transit agency on a simulation, it begins by asking cities what they hope to accomplish, and looks at vehicles that a city owns that could be used for the new service (while the technology could be used with full-size city buses, it often might make sense to repurpose smaller vans or even supervisor vehicles). Then it plugs in as much data as a city has available. In the past, the company used its algorithm to manually run simulations with the agencies it has worked with so far; the new simulator automates and streamlines the process, helping make it more accurate.

Just because people could use microtransit doesn’t mean they will. “Where it gets a little complicated isn’t really in the data, but it’s that intangible behavioral characteristic,” says Kumar. “How to shift the mind-set of a user, how to shift their behavior and travel patterns, is much tougher than what the data will show.”

When Kansas City ran an experiment with the microtransit company Bridj in 2016 (the startup shut down in April 2017)–offering on-demand rides in the downtown area for $1.50, with the first 10 rides free–only a tiny fraction of people in the area actually used it. In a survey halfway through the year-long test, 40% of people in the area said that they didn’t know it existed. In Finland, Helsinki’s experiment with an on-demand shuttle called Kutsuplus was more popular, but closed down because the city decided it was too expensive.

Still, TransLoc believes that its simulator can make testing a new microtransit service less risky for cities, and it’s talking with dozens of agencies. “I have never seen the market move as quickly as it has toward this demand-driven transportation mode,” says Kumar, who has worked in the public transportation space for 20 years. “I think part of it is that people have an expectation now that things should be on-demand.”

That doesn’t mean that traditional public transportation will disappear, but in the future it may be more seamlessly connected to microtransit, and later, self-driving cars. “There is still going to be a place for fixed-route transportation, high-capacity transit, whether it’s a subway, heavy commuter trains, or even buses,” says Kumar. “Things like microtransit, Uber, Lyft, and others will fill in the blanks, so a city will have fair and equitable transportation regardless of mode. We really believe that we have to blur the borders between modes and optimize everything together.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.