Walking into Artsy’s New York headquarters, 26 floors above Chinatown, feels like encountering a monumental blank canvas in a light-drenched artist’s studio. The walls are white. The furniture is white. On a bright spring morning, shadows slide across the desks of 140 employees as the sun traces Canal Street from east to west.

And then, in an all-white conference room, a tall figure appears: CEO Carter Cleveland, a Franz Kline-esque vertical stroke dressed in head-to-toe black, with sharply angled dirty-blond hair and a silver bracelet on his wrist. Cleveland started building Artsy in 2009, while he was a Princeton senior studying computer science. Today, he’s announcing $50 million in Series D financing, bringing Artsy’s total dollars raised to over $100 million. The funding is a clear sign of validation for a startup whose list of investors reads like the seating chart for a society-pages dinner party: Wendi Murdoch, famed gallerist Larry Gagosian, and members of the Rockefeller family, to name just a few. Avenir Growth Capital, a New York-based firm, led the round.

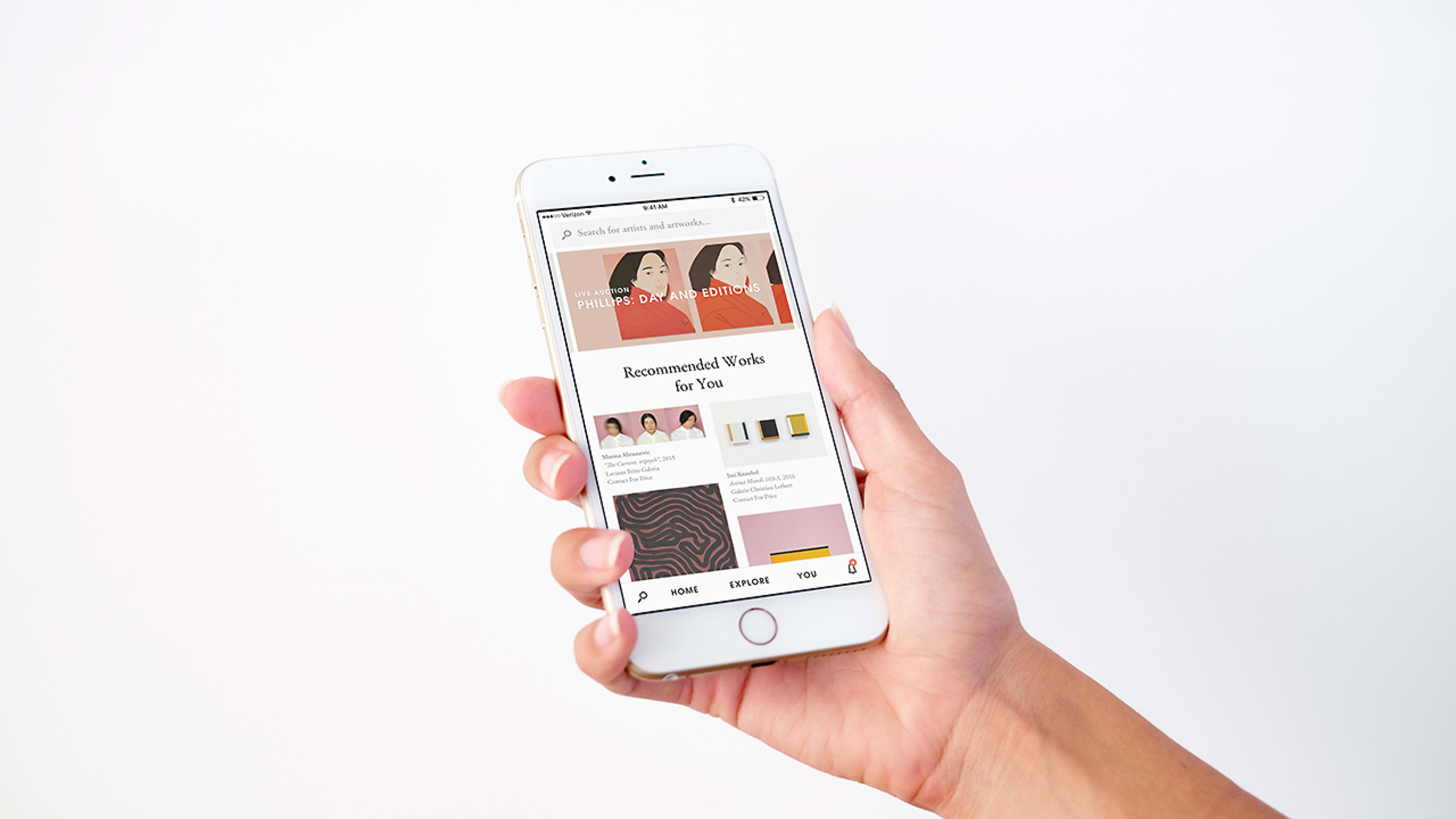

“People don’t want to download one app for every gallery, one app for every art fair, one app for every museum, one app for every auction house,” Cleveland says. Instead, they can use Artsy, a central platform that contains works from 1,800 galleries and 25 auction houses. From the buyer’s perspective, Artsy combines those primary and secondary markets into one digital experience as intuitive as Instagram. The galleries pay a subscription fee for access to Artsy leads; the auction houses, on the secondary side, use Artsy as a bidding channel for online sales. Over 2 million unique visitors explore the site and its 800,000 artworks each month.

“Traffic is what allows us to scale,” Cleveland says. “You expand the market by making all this inventory accessible to a much broader audience—make it easy to discover, to learn about, and ultimately to buy.”

It’s a remarkably democratic mission for a company that got its break by winning over the likes of Murdoch, who sits on the board, and her Art Basel-set friends. But after years of gradually building out the Artsy platform and its massive art database, piece by piece, Cleveland appears poised to achieve it. Not coincidentally, many of his competitors have recently gone bust. In the last year, there have been mass layoffs at Artlist, Artspace, and Paddle8, which merged with Berlin-based Auctionata only to find itself embroiled in the German equivalent of bankruptcy proceedings. Paddle8 further “gutted” its staff in February. Artsy, in contrast, is hiring for over a dozen roles.

The difference in outcomes boils down to a fundamental difference in strategy. While rivals tried to challenge the art-world establishment head on, Artsy chose to partner. “We always intuitively thought those other vertical models weren’t going to be as scalable, but it’s scary at the time to see another competitor going up really fast in revenue when you’re not,” Cleveland says. “To be a partnership model, to aggregate everything into one place, means we had to wait a little bit longer until we started seeing those transactions. Now the roles have switched.”

Painting The Town

Online art sales represent a small but growing segment of the market overall, rising 15% to hit $3.75 billion in 2016, according to a report published by insurance broker Hiscox. Critically for Artsy, four of the top 10 online art platforms last year, in terms of sales, were traditional players with digital offerings—suggesting “that the power balance might be shifting back to the incumbent art market players,” Hiscox wrote. Artsy stands to benefit from that dynamic if the company can continue to deliver customers that incumbents would otherwise fail to capture.

Sebastian Cwilich, Artsy’s president and chief operating officer, likens the company’s role to “bringing more people to the party.” A former Christie’s executive, he has successfully pitched Artsy to his former peers at Phillips and Sotheby’s. “You are putting all this work into acquiring this incredible inventory and you’re marketing it and you’re writing about it and you’re pricing it and you’re authenticating it—and then what we can do, for a third of those works, we are going to raise the prices at which they sell,” he says. “You ask any auction executive, even one more bidder in the room can be the difference, a giant difference in how much money they make.”

This year the company is on track to quadruple the number of auctions it hosts. For Megan Newcome, director of digital strategy for Phillips, it was a compelling offer. Her team started experimenting with Artsy’s online auction integration earlier this year, with promising results. For example in May, at Phillips’s 20th Century & Contemporary Art & Design evening sale, a George Condo painting sold to an Artsy bidder for HK$2,480,000 ($317,841), beating the estimate.

“Artsy built a sophisticated infrastructure to better support what auction houses and galleries and art fairs are already doing, and widen the communities that they engage,” Newcome says. “Using data to be able to predict and recommend what people would be interested in—that’s really the future. The short game is to reinvent the auction house online. The long game is where Artsy is at, and it’s around this data-driven approach to something that’s a very passionate and emotional thing.”

Data Has Its Limits

Cleveland founded the company with a thesis around the importance of data, and a complementary appreciation of art’s intangibles. He had grown up in a home filled with art (his father is an art writer) and set out to build the art equivalent of Netflix or Pandora, companies that live and die by their inventory and recommendations. Early press hailed his “Art Genome Project,” a reference to Pandora’s approach. But as Pandora similarly realized, data science alone is not a selling point. Users simply want to find music and art that they enjoy. Over time, the Art Genome Project has shifted to the background, where it still generates suggestions but with less fanfare. Now Artsy’s search engine-friendly editorial content serves as a user hook, with blockbuster posts like an analysis of Italian sculptor Bernini’s erotic works helping to attract newsletter subscribers and social media fans. On Instagram, Artsy has over 500,000 followers.

That is not to say that Cleveland has given up on data. Earlier this year he and Cwilich, an applied mathematician by training, acquired ArtAdvisor, an analytics startup focused on the art market, and installed its cofounder, Hugo Liu, as chief scientist.

“He brings a whole new level of sophistication where it’s not just about recommending other artworks that you might like based on your interests, it’s actually now understanding more the context of why is this art valuable,” Cleveland says of Liu. “We think that’s a really important part of expanding the art market—creating a broader awareness and education that art is something, like a home, that can be a hold of value.”

Pricing intelligence could be equally valuable for Artsy’s partners. “Even though a gallery might understand an artist very well, what we have a really good sense for is that whole, broader context,” Cleveland says. “Being able to provide the gallery with guidance on the best price ranges for their artwork we think will be very helpful.”

In the early days of online art, sellers were focused on proving out that buyers would pay for original works, sight unseen. As recently as 2015, Cwilich told the New York Times that buyers were most comfortable with price points under $5,000. Today, he says, the average price point is more than double that, and rising. And the bigger the ticket, the higher the stakes.

It will take some convincing to get galleries on board with the idea of setting estimates with help from an algorithm. They take pride in their knowledge of the market, and continue to see value in a high-touch sales process. “With a lot of the art-sale sites, the common pitfall is this idea that you can just throw a bunch of art online with a ‘buy it now’ button and expect something to happen. That’s not how art is sold in galleries,” says Austin Kennedy, design director at Pace Prints, which represents artists including Chuck Close and Sol LeWitt. “The way that galleries show and sell art is a touchy-feely process, it’s a very personal process. Quality over quantity is always key.”

Kennedy credits Artsy with helping expand the audience for Pace Prints, and gives high marks to the inquiry system that the company developed for managing leads. But he is hesitant regarding Artsy’s data ambitions. “Art is not a consumer product. It’s a very individual thing. It only takes one person to have an interest or a passion for something.”

That is certainly true of Cleveland’s own preferences. One of his most beloved pieces is a work by ’60s-era sculptor Wendell Dayton, purchased on Artsy. “I love his style and feel a strong personal connection to the artist through his son, Sky Dayton, who’s been an Artsy board member for several years,” Cleveland says. “I love discovering art with a strong personal connection and am inspired when artists, like Wendell, who’ve been developing their practice for decades, experience a renaissance later in their careers.”

For Cleveland, that love had a price. For Artsy, the future depends on being able to quantify exactly how much.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.