After voting to officially legalize marijuana nationwide starting in July 2018, Canada has the next year to figure out exactly how the drug will be sold and regulated. Canadian health experts face some concerns about how to create more availability of the drug, but also do it responsibly. To them, the danger isn’t legalization, but the commercialization that accompanies it. What happens when profit-minded suppliers compete? Business 101, of course: In order to thrive, most companies generally try to attract more customers and/or convince existing ones to use their products more often.

When it comes to controlled substances, though, strategies like that might cause some trouble. There’s a fine line between popularizing use and enabling abuse, the fallout of which can already be seen both in some newly legal weed markets and, historically, with other products associated with unhealthy behaviors like tobacco, alcohol, and, more recently, opiate-based medications.

The group would be able to ensure a proper standard for testing to affirm the safety, strength, and uniformity of the product, as well as place limits on packaging promises and marketing messages, in addition to tracking what’s being sold. “If people want to use, that’s their own thing,” says Gagnon. “[But] we tend to see more harm from these products, so we want [people] to stay healthy and alive.”

In Canada, cannabis use is at its lowest in a decade: Just 15% of the population reports getting high within the last 12 months. Gagnon is lobbying for a rollout with practices that continue to stress “harm reduction”—curbing things like accidents while driving or operating heavy machinery, addiction (yes, it can happen), and future respiratory disease.

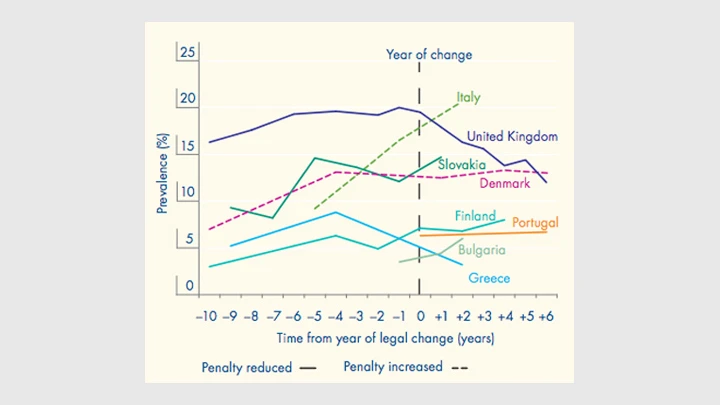

Based on a report from the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Addiction, it seems as if relaxed laws alone don’t necessarily correlate with increased consumption. In fact, a study tracking countries over a 10-year period found that in some places where the penalties have decreased over time, notably the U.K. and Greece, there were actually similar drops in use rates. In Italy, when the consequences went up, so did the number of people toking, while in Slovakia, the risk of greater repercussions simply had no effect.

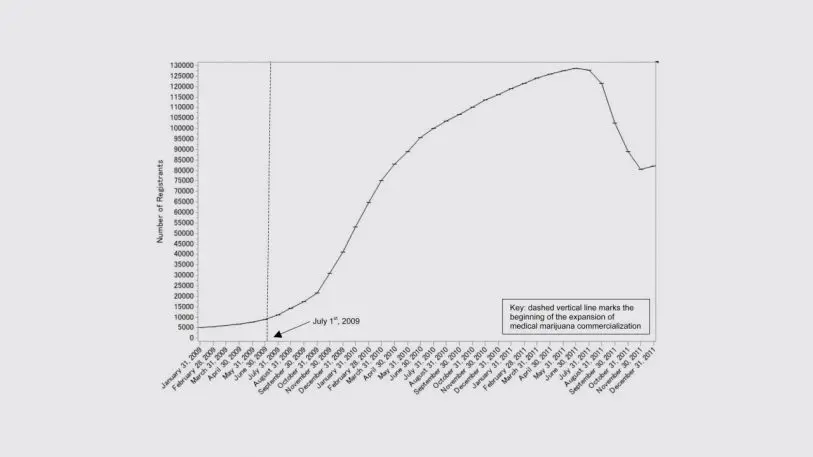

Two more charts, which Gagnon often trots out in his webinars, show something completely different happening in the U.S. First, once medical marijuana was legalized for medical purposes in Colorado in July 2009, the number or program registrants jumped nearly tenfold in one year, from about 11,000 in July 2009 to nearly 100,000 12 months later.

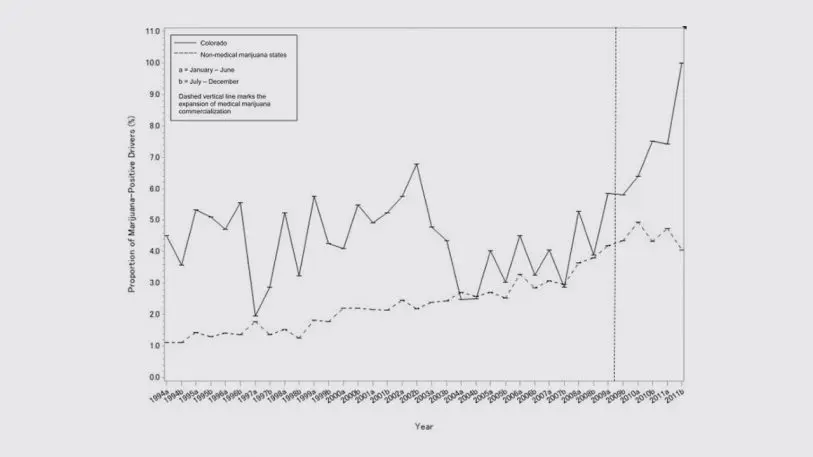

Second, there was a massive spike in reports of stoned driving, which causes drivers to be twice as likely to have fatal accidents.

Since cannabis became fully legalized, Colorado has recorded the highest use rate of all states: 17% of adults have used the drug within the last month, more than double the overall rate elsewhere. Post-legalization, cannabis-related poison control calls have spiked, as have hospitalizations.”I think part of the reason use has been going up in Colorado from before legalization is because [cannabis] has been aggressively promoted there,” says Gagnon.

Since cannabis became fully legalized, Colorado has recorded the highest use rate of all states: 17% of adults have used the drug within the last month, more than double the overall rate elsewhere. Post-legalization, cannabis-related poison control calls have spiked, as have hospitalizations.”I think part of the reason use has been going up in Colorado from before legalization is because [cannabis] has been aggressively promoted there,” says Gagnon.

For perspective, even Amsterdam isn’t really interested in living up to its tough-puffing reputation anymore. After realizing that spikes in both use and tourists being ridiculous correlated with the proliferation of federally sanctioned “coffee shops,” the Netherlands has actually reduced its number of available shop locations in recent years, leading to reduced use.

Gagnon thinks his model will work perfectly in Quebec, which already has state-controlled wine and spirits shops, and has created extensive nonprofit partnerships to improve everything from its kindergartens to affordable housing. “It is impossible to know what elected officials will decide,” he adds in an email. “Public statements made in Quebec are not always coherent, but overall indicate that everything is on the table right now.”

It’s less likely that other provinces would follow suit, simply because they have less experience with similar regulations. If all else fails, nonprofits would probably still be able to apply for retailing licenses, Gagnon adds, allowing groups to create an alternative point-of-sale network, with perhaps more trust and less profit motive.

Gagnon’s fully baked model has been successfully piloted elsewhere already. Since legalizing cannabis in December 2013, Uruguay has controlled sales (and health concerns) through the Institute for the Regulation and Control of Cannabis, which monopolizes purchasing and distributes through a network of pharmacies. Before going on sale, THC-contents are tested, ranked, and branded accordingly.

Across Canada, the door is still open for nonprofit growers, too, although they might have to compete with commercialized counterparts. In Quebec, particularly, Gagnon foresees the potential for people to eventually contract directly for shares of local farmers’ harvests, the cannabis equivalent of CSA farming. The province already supports a robust community-based, vegetable sourcing network. (Belgium does something similar for weed already.)

Long term, designing a system that increases liberty but limits health risks makes pretty good financial sense. Collecting tax revenues from a new industry is one thing, but when it comes to controlled substances in unrestricted markets, those fees don’t generally keep pace with the toll of related medical costs and lost work. The U.S. may collect $27 billion in smoking-related taxes, but it loses $170 billion in smoking-related health costs.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the final deadline, June 7.

Sign up for Brands That Matter notifications here.