As Amanda and Chance Richie were getting ready to spend a seven-figure sum on a flailing but historic fast-food chain based in Flint, Michigan, news reports around the world were highlighting the horrifying spectacle of an entire U.S. city’s water supply poisoned by both lead and government mismanagement. The couple thought they knew what they were getting into, but after they closed on Halo Burger in January 2016, they quickly realized that reading about Flint’s water disaster couldn’t begin to prepare them for the reality of a community in crisis.

Listening in as kitchen workers talked about their sick children and struggles to deal with a lack of usable water, the Richies started to get a sense of the challenge ahead of them. “It’s not that we weren’t aware of what was happening, but it’s different when you become part of a community that’s in so much trouble,” says Amanda, 41, as she and her husband sit in a booth one morning at Halo’s flagship location in downtown Flint. “This was scary. We realized we had taken on a responsibility that was more than serving hamburgers.”

This is tricky territory for any business to navigate: how to be a good corporate citizen without coming off as self-serving or exploitative. But given the severity of Flint’s situation and the extent to which it touched everyone in the community, finding that balance was going to be even more difficult. The Richies wanted to help because it was the right thing to do. But they also knew they’d need to do it in an effective and authentic way, or else it could seriously damage their new business. As Amanda puts it, “The water crisis was either going to be an opportunity or the death of the Halo Burger brand.”

Halo Burger is almost as old as fast food itself. Launched in Flint in 1923—just two years after White Castle, America’s first hamburger chain—the restaurant was originally called Kewpee Hotel Hamburgs. By World War II, there were more than 400 Kewpees across the Midwest, but the business slowly unraveled after its founder died in 1945. William V. Thomas, a counter clerk-turned-franchisee, took over the original Flint location in 1942, and by the 1960s he was the last Kewpee operator paying the franchise fees. Thomas and his son, Terry, renamed the business Halo Burger in 1967, expanding to a peak of 13 locations around Flint by the 1990s. Despite the name change, the Thomases kept the Kewpee Burger on the menu, tweaking it to “QP” to avoid trademark conflicts. “We just said that was for ‘quarter pounder,'” chuckles Terry Thomas, now 76 and living part-time in Cocoa Beach, Florida (William died in 1973). Halo still boasts other Kewpee originals, including a hamburger smothered in olives and a vanilla ice cream float made with classic Detroit ginger ale Vernors.

Terry sold Halo, then down to nine locations, in 2010 to Dortch Enterprises, “and I regretted it ever since,” he says. Dortch, which owns dozens of Subways shops in Michigan, hoped to turn Halo into a national brand that would compete with growing fast-casual burger chains such as Five Guys and Smashburger. The company added six locations in the Detroit suburbs and in Lansing, Michigan, but ultimately that ambitious vision didn’t pan out, and in the spring of 2015, Dortch put Halo on the market.

Around the same time, Chance Richie—a self-made multimillionaire who founded and then sold a business that developed an environmentally conscious process for recycling fracking wastewater—was looking for a new challenge. At first, he and his wife (who also runs a Michigan-based specialty chemical company she inherited from her father) contacted Sonic about opening franchises in southeast Michigan. Sonic executives suggested they buy the Halo restaurants and convert them into Sonics, but the Richies had a better idea. They and their five children already liked Halo’s food, having stopped in many times on the way to their vacation home in northern Michigan, and they became enamored of the possibility of reviving such a historic local brand.

In October 2015, they began to negotiate with Dortch. The water crisis was just starting to break. Weeks earlier, a local pediatrician and a scientist at Virginia Tech had proven that Flint’s water supply was tainted by toxic, illegally high levels of lead—something locals had been insisting for months, despite efforts by the city and state government to dismiss their concerns. Thousands of residents of this poor, mostly black city of 100,000 faced the prospect that their children’s physical and mental health had been seriously harmed.

Many entrepreneurs would have run away from a community confronted with a crippling long-term health crisis, but the Richies instead accelerated the purchase. Though they won’t reveal what they paid, they say they didn’t ask for a price reduction. In January 2016, they closed the deal on Halo’s 15 outlets. They were now the proud new owners of a distressed brand in a traumatized city.

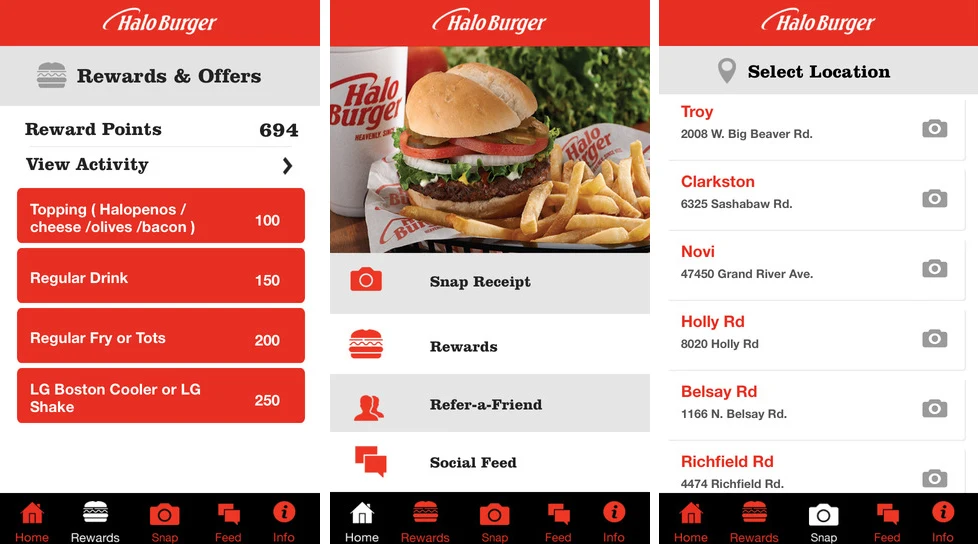

The Richies quickly started to implement their turnaround plan, which involved improving ingredient quality, lowering prices, and raising pay for employees. They closed five underperforming restaurants and plowed $2.5 million into store renovations, upgraded computer systems, and compensation. The couple also started supporting the local community by tapping in-state vendors for their beef, buns, pickles, cookies, and packaging. “We’re going to simplify operations to lower our food costs, reduce waste, and improve food quality and speed of service,” says Chance, a muscular 45-year-old who favors tight-fitted T-shirts and skinny jeans.

But given the water disaster, which by that point was a big national story, the Richies knew those steps weren’t enough. They soon convinced Coca-Cola—which supplies soda to the chain—to offer free cases of bottled water for the public to take home at all of Halo’s Flint locations. They collected $48,000 through counter jars and store fundraisers for food trucks that delivered fresh produce to low-income areas, an effort to improve nutrition in ways known to help avoid or alleviate lead absorption in the blood. And they began to offer health insurance to employees working at least 20 hours a week because improved access to medical care seemed necessary to cope with the problems caused by lead exposure. “We firmly believed that Flint was very resilient,” says Chance. “If you put something into [the community], you’re going to get it back in return. Does the RoI work out? By dollars and cents, no. But from a brand-perception [perspective] and what we want to do with the overall company, it absolutely makes sense.”

Flint seems to have responded to their efforts. Revenue rose 14% in 2016 and is up more than 10% year-over-year so far in 2017, the owners say. That suggests a significant uptick in customer traffic, especially considering that they closed one-third of the locations, increased starting pay from $7.90 to $9 an hour, put 37 of about 250 employees on a health plan, and saw a 4.4% drop in the average check. “Did we see people be really positive towards us because we invested right away? Yeah, absolutely,” Amanda says. “We got a ton of great press, we got a ton of customers coming in thanking us for being part of the community. We had people reach out to Chance and me. But that’s not why we did it.” University of Michigan business professor Rajeev Batra describes this kind of approach to community outreach as “enlightened opportunism. It can be cynical if it’s inauthentic, or it can be sincere,” he says. “People can tell the difference.”

Today, the Flint crisis has quieted down somewhat as the city, using tens of millions of dollars from the state and federal government, is replacing lead pipes, and water-treatment changes have improved its quality. That has allowed the Richies to focus more on expanding Halo Burger. They plan to open five new sites by next year, with a goal of hitting 60 across the state by 2022. They’ve also revved up a new marketing campaign centered on Detroit Pistons star Andre Drummond, and they are currently negotiating to lease space at the new Little Caesars Arena in downtown Detroit when the Pistons move there this fall.

But no matter how big Halo might grow, the Richies intend to keep the business’s home community at the center of its identity. “We plan to be clear to everyone that this started in Flint, that this is a Flint business,” Chance says. “It’s something we’re proud of and the people of Flint are proud of. We can represent something good coming out of a place where people only hear the bad. We rode out the storm together.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.