Picasso paintings have sold for hundreds of millions of dollars in recent decades, but that wasn’t always so. In fact, one of the jewels of New York’s Museum of Modern Art—his 1907 cubist masterpiece Les Demoiselles d’Avignon sat in storage for years after it was originally derided as immoral.

By the 1920s, however, the genius of what Pablo Picasso was doing on canvas started winning fans. A French collector paid $1,300 in 1924. Months later, he sold Les Demoiselles for 10 times that. And then, in the late 1930s, in preparation for a major exhibit of the artist’s work, MOMA plunked down $24,000 (the equivalent of about $340,000 in 2017 dollars).

Today, the work is thought to be worth untold millions—it’s not for sale. But if it is any comparison, Picasso’s Women of Algiers sold at auction for $179 million two years ago.

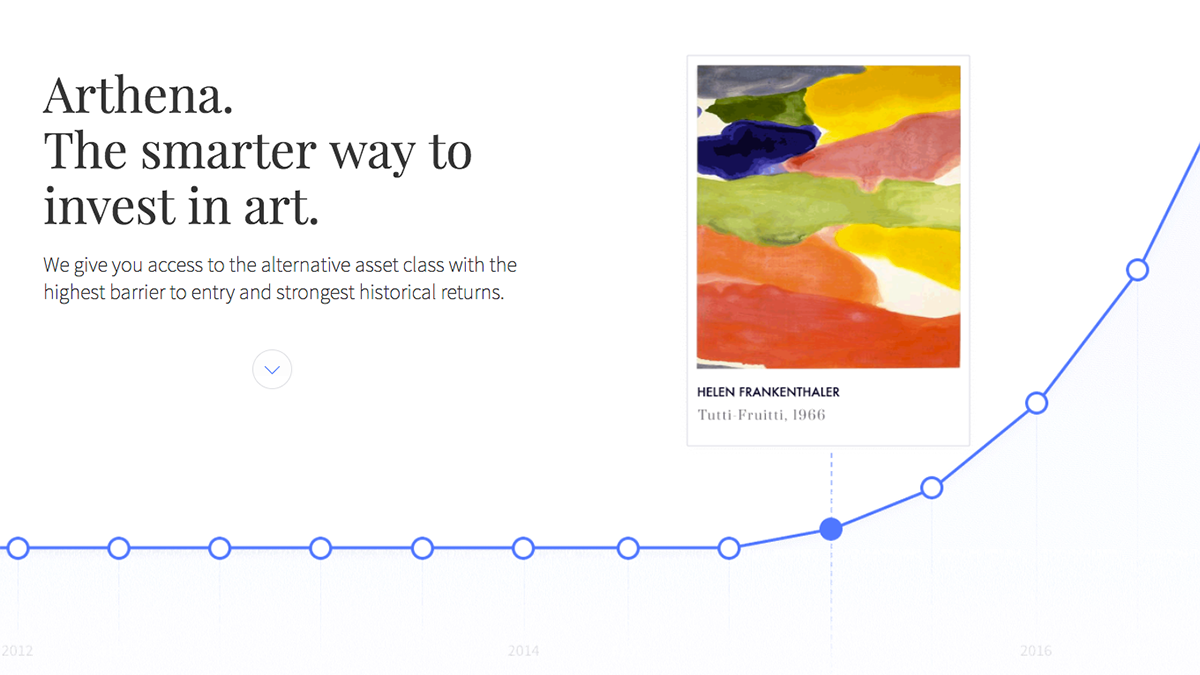

What if there was a way to get a piece of that action without owning any artwork? To know in advance that your investment will bring you handsome returns? An innovative startup called Arthena is striving to do just that—to “democratize,” in its words, the buying and selling of fine art, which has long been the playground for the super rich.

Most investors put their money in quantitatively driven funds that buy stocks and other securities based largely on mathematical formulas. Think your 401k. Fund managers use historical data and information about company performance to pick stocks that seem like bargains, betting prices will rise and their investors will profit.

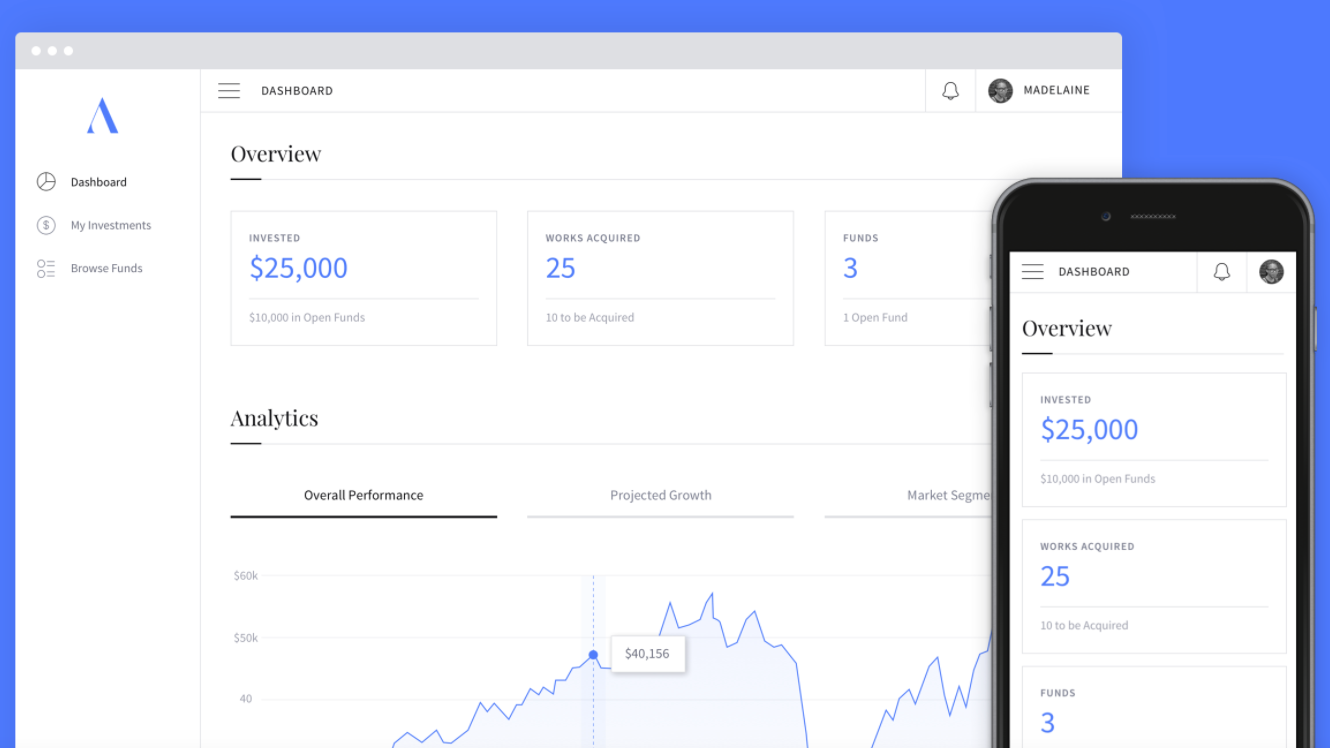

Arthena, founded in 2014 and with offices in New York and the Bay Area, is applying those same quantitative investing principles, using an algorithmic approach to build funds that let investors add art to their portfolios.

“We believe we are building the next big asset class,” says cofounder and CEO Madelaine D’Angelo.

Arthena mines a dataset of millions of historical sale prices and dozens of other attributes to locate art likely to gain in value at a rate of about 20% per year. It then lets investors contribute to funds that buy and sell that art that is then safely ensconced in an art storage facility—and potentially made available to museums for loan and, if all goes well, ultimately sold to return a healthy profit to investors.

While investors don’t get the intangible benefits of directly owning art, like being able to show a beloved collection off at a cocktail party or lend pieces to a favorite museum, they also don’t have to deal with the hassle of storing and preserving individual pieces, and insuring them in case they’re stolen or damaged by a clumsy houseguest.

Arthena raised $20 million in investments for a new fund investing in a mix of art from the modern and postwar eras and the present day while participating in startup incubator Y Combinator’s recent winter round, and is attracting interest from people who haven’t previously collected or invested in art, says D’Angelo.

“Most of the people investing are completely new entrants to the market,” she says.

The company also offers a variety of funds emphasizing different eras of recent art history, but for investors the choice is as at least much about taste for risk as it is artistic taste. Funds focusing on established masters of the Modern era—illustrated on Arthena’s website by Picasso’s Girl before a Mirror from the 1930s—are advertised as a stable store of wealth; and funds buying familiar artists from the postwar period are dubbed “blue chip artists” for those with a “moderate risk tolerance.” For more aggressive investors, Arthena offers funds investing in “rising emerging” artists of recent years, perhaps the art equivalent of investing in a rising tech stock.

For now, the ability to put money in an Arthena fund is limited to SEC accredited investors—generally individuals with annual incomes of $200,000 (or $300,000 for a couple), or $1 million in assets, who are considered to have the resources and sophistication to invest in less-regulated securities.

If Arthena’s approach can continue to attract new funds to the art market—and D’Angelo says she’d like to one day see the company’s funds open to a less restricted set of investors—that can ultimately mean more money to support working artists and the galleries that exhibit their works.

“Adding volume is something the art world has talked about for decades,” D’Angelo says.

Still, Arthena’s approach may not be for an investor looking for a purely data-driven investment, because there’s still a level of subjectivity inherent that is not usually part of the equation for quantitative investments in purely financial markets—like input from experts on trends, buzz, and their gut instincts.

Arthena has been able to run analyses like computing which artists’ works best correlate with each other in terms of sale price, something that’s more complicated than just seeing which participated in the same movements or worked in the same era, she says. And since art investments are ultimately in individual works, not artists—investors and collectors can only buy individual pieces, not 50 shares of Pablo Picasso or five ounces of Georgia O’Keeffe—the company also tracks how aesthetic factors, like the size and color of individual works, can influence prices.

“Things like certain colors from certain artists do better than others,” says D’Angelo.

The company has made clear that it won’t robotically rely on data and algorithms to make investment decisions and that “traditional appraisal” is also a part of its methods. Human analysts study art that’s up for auction and can adjust machine-generated price and growth estimates based on their findings and “knowledge of the art world,” as well as non-numeric data like formal reports of artworks’ condition, the company says.

D’Angelo emphasizes her own background in the art world, a certified appraiser with a master’s degree from Harvard and experience working at the Smithsonian Institution and Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. Her brother Michael D’Angelo, who studied applied math and machine learning at Stanford, is the company’s CTO.

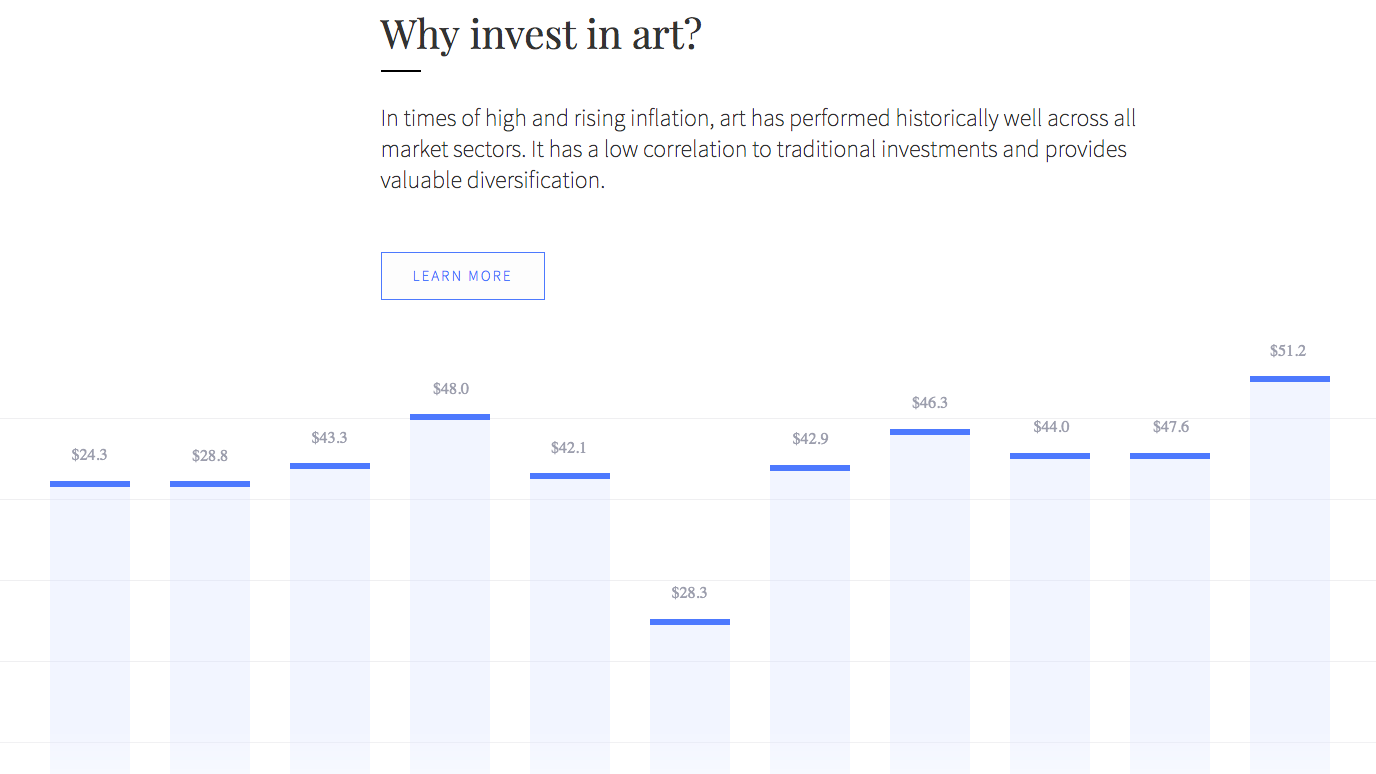

Arthena says it’s the first company to build a quantitative approach to building art investment funds. But it isn’t the first company to put together pools of investors to speculate in art: a report issued last year by Deloitte and the London art market research firm ArtTactic estimated the global art fund industry had about $1.2 billion under management in 2015, though the authors cautioned there are likely other, private pools of money investing in art as well.

“There’s a lot of a little more private, under-the-radar sort of vehicles,” says Anders Petterson, founder of ArtTactic. But in general, the report estimates that the art fund market is down from a peak of $2.1 billion under management in 2012, partially as a result of what Petterson says is limited investor demand.

Art funds are often too small to woo big institutional investors like pension plans. And the funds can rise or fall based on how easily their managers can find the right works to invest in at the right price in what can be a tricky art marketplace. Unlike stocks, or commodities like oil or gold, individual paintings or sculptures aren’t neatly interchangeable, and they can’t always be immediately bought or sold.

And private art dealers sometimes make sales and set prices based on considerations other than immediate profit. One consideration might be the boost to an artist’s reputation of having works in a particular private collection, Petterson says, perhaps not too different from the benefits to a tech startup of winning an investment from a prominent incubator or venture firm.

“This might change in the future, but [an art] fund doesn’t really add much to the artist’s reputation,” he says.

And some investors, particularly younger ones, have shied away from the market because of the lack of available data. Only about 40% of art sales take place through auctions, leaving many other transactions hidden from public view, says Andrea Danese, CEO and president of Athena Art Finance, a New York company offering loans using art as collateral.

As The New York Times reported last month, even expert estimates of the size of the art market in a can vary by billions of dollars from year to year. That uncertainty has repelled many wealthy millennials used to up-to-the-minute stock quotes and a web full of data on other investments, says Danese.

“They’re absent because they’re used to the complete transparency and access to information in the age of the internet,” he says. “They hate the art market because it’s not transparent.”

Longtime market participants still rely on their gut instincts when visiting art fairs or getting a sense of the buzz around an artist, as much as they have access to spreadsheets of historic prices and other data, says Suzanne Gyorgy, global head of art advisory and finance at Citi Private Bank.

“I think that there’s a frustration in the inefficiencies and people want to correct it, but because it’s part of what the market is and what people like about collecting art, I don’t see it necessarily being corrected,” she says. The art market may rely on private dealers and behind-closed-doors sales, inefficient or not, even after person-to-person securities trades on stock exchange floors are a distant memory.

Arthena has drawn some derision for its more-or-less purely financial approach to the art world.

“We were voted as the ‘best way to suck all the joy and humanity out of art’ by the Village Voice this past December,” says D’Angelo.

Many artists have long approached the more mercantile aspects of their profession with mixed feelings but that is changing, says Roderick Schrock, director of Eyebeam, a New York nonprofit supporting artists working with technology. particularly in recent decades as the market for trendy works has grown.

“I think that over the last ten years, as the art market in some ways become even hotter than we had thought was being possible ten years ago, as that happens it does tend to create a sense of necessity around self-commodification around artists,” he says. That is, artists have a natural tendency to tweak their work to cater to the demands of the art market and the buyers who ultimately pay the bills. And that’s a tendency that may well grow if art prices begin to be shaped by digital rules as much as shifting tastes.

“I think as more algorithmic and machine-learning processes are implemented in the market, that will probably intensify,” Schrock says.

Save

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.