When Edward Snowden blew the lid off of the NSA’s mass surveillance program, he also revealed the extent of the government’s smartphone location tracking records. As the Washington Post reported in 2013, the NSA is gathering 5 billion records a day on people’s cell-phone locations across the globe in order to track terrorists and identify their associates. While the U.S. must often take the data surreptitiously, however, advertisers are already getting many of our locations legally, through our smartphone apps; mining that and other data fuels the billion-dollar businesses of some of the world’s largest companies.

And as a number of studies have shown, even when it’s “anonymous,” stripped of so-called personally identifiable information, geographic data can help create a detailed portrait of a person and, with enough ancillary data, identify them by name.

Curious to see this kind of data mining in action, I emailed Gilad Lotan, now vice president of BuzzFeed’s data science team. He agreed to look at a month’s worth of two different users’ anonymized location data, and to come up with individual profiles that were as accurate as possible.

The results, produced in just a few days’ time, range from the expected to the surprisingly revealing, and demonstrate just how “anonymous” data can identify individuals.

(To gather the data, two people, whose real-world identities were known only to me, logged into Google Maps’ Timeline web application and downloaded a copy of their location data in JSON format, which I then sent to Lotan. Their settings permitted Google Maps on their Android phones to collect geo-data at all times.)

“Companies often claim to have ‘anonymized’ your location history by taking your name off it,” says Peter Eckersley, the chief computer scientist of the Electronic Frontier Foundation. “But that is totally inadequate because you’re probably the only person who lives in your house and who works in your office, and it’s easy for any researcher or data scientist to look at a location trace and figure out who it belonged to.”

Mapped sequentially, a person’s location history, as he puts it, looks like a spaghetti line that folds itself through space: It moves backwards and forwards from home to office, occasionally stopping at a friend’s house or at a grocery store.

“Any time you go to a medical clinic, or a church, or a political meeting, or spend the night at someone else’s house, those facts are eloquently revealed by your location,” says Eckersley.

While much of Lotan’s work was technical, some of it involved a combination of keyword searches and guesswork. He began exploring the data by asking himself about the “shape” of the data and and whether it was clean or if he had to remove outliers.

Once the noise is out, “then you ask, ‘Well, how do I understand patterns where I have many millions of rows in this massive spreadsheet, like this time and this location, this time and this location?'” he says.

The location data is granular–latitude and longitude to within five, six, or seven spaces after the decimal place, so a few feet or meters in terms of accuracy of location. But “if we want to understand a place a person is in we don’t actually need such accuracy–what we want to do is group locations by proximity.”

When de-anonymizing data isn’t easy: “No Clear Work Pattern”

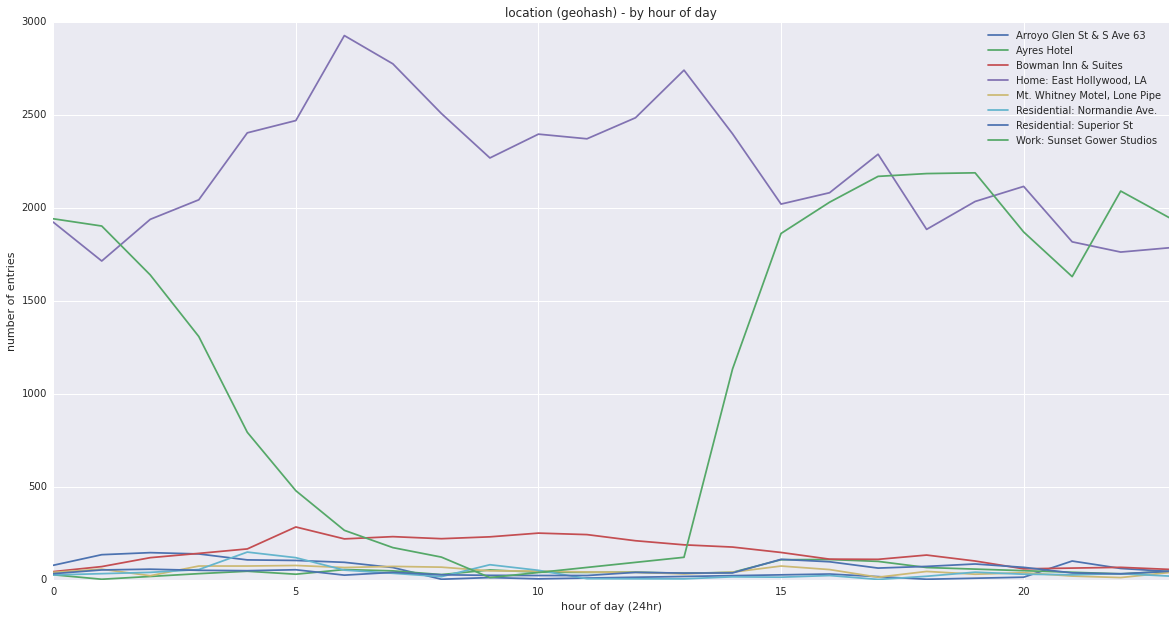

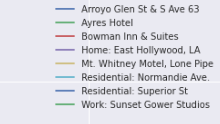

For the first anonymous person, “what struck me is that there was no clear work pattern.” He deduced that this individual worked at Sunset Gower Studios in Hollywood, “and I knew which studio this person was at–I mean, even which number. I could have even figured out which production they were working on if I called the studio up. I did try to look at Instagram to determine this, but it didn’t really work out, but I had the times they worked there.”

Lotan tracked the person to Greystone Mansion in Beverly Hills, and noticed that they visited various lighting stores, other sound stages around Los Angeles, as well as some restaurants. “They were also in North Dakota in these crazy rural locations, possibly filming something,” says Lotan.

The target’s movements made it hard to determine where they lived. There was a residential address, but the person also visited many hotels and traveled frequently. “There were even hotel stays in Los Angeles, and this threw me off. I did notice through Google Street View that there was construction next door, so I thought maybe the landlord put this person up in hotels,” says Lotan.

Of their apparent residence in East Hollywood, “it was probably a rental, which is probably why there wasn’t a lot of information about it [online]. The person spent a lot of time in the park next door, so a dog or kids maybe?”

The granular information provided by GPS data can also show where in their house a person tends to spend their time, says Lotan. In this case, they lingered in the backyard.

How’d Lotan do? The target, a 35-year-old male with a girlfriend but no kids, does indeed work in the film industry as a gaffer. The job takes him all over Los Angeles and other parts of California, and he also travels quite a lot on his own.

The second anonymous user was far easier to profile because, as Lotan points out, when a person takes out a mortgage on a house, that data becomes publicly available. And determining a person’s home location can open up a window into their entire identity.

When De-anonymizing Data Is “Super Easy”

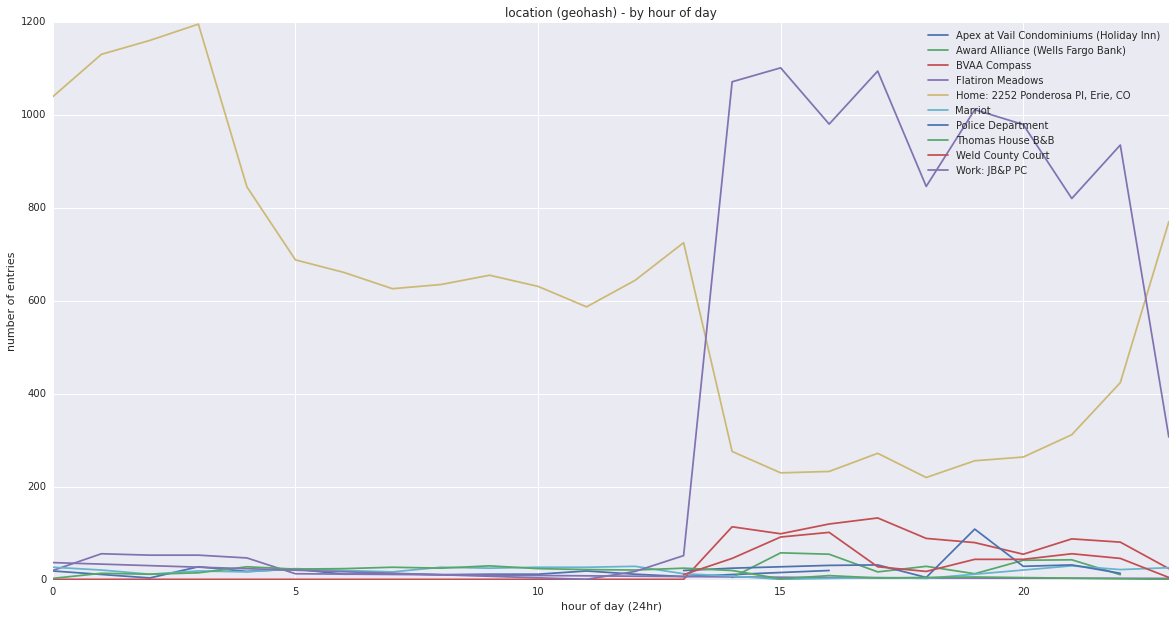

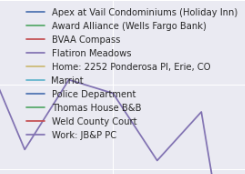

“It was very easy to figure out the home address,” he says, of a location in Erie, Colorado, just outside of Boulder. “The granularity of the geo-hash was a little challenging because the house is residential, but it’s very clear what that address is.”

“There is a very clear handoff between the work line, which is the purple line, and home, which is the yellow-orange. Work was a little harder, because there was a number of different offices there, but because there is height [data] it makes it pretty easy to figure out that he is likely in this law firm, JB&P.” He also determined that the person often visited the court or police department in a way that fit the profile of an attorney.

Lotan determined that the person definitely had a car, which they would leave for extended periods of time in a parking lot. The person also visited Wells Fargo frequently, suggesting that they had a bank account there.

It wasn’t hard to determine that the person had kids, too: They spent a lot of time at Chuck ‘E Cheese, waited at a school drop-off, and visited places like Kids Academy.

“And because this person owns this house, there is more information there,” says Lotan. Using a simple Google search, “with the address you can get a very clear residential listing, which is published by Dun and Bradstreet, a business services company dealing with credit reporting.” An address yields “the full name of the owner with the middle initial, and just with this name you can get his Facebook and get to his place.”

“I don’t know why they have this data, but they do,” he says. “I didn’t expect to find this so easily because I didn’t pay for any data, I just used Google. Once you have the link and name, you can get a lot more social profiles.”

“It’s super easy. You can get to LinkedIn, and confirm that they worked at the law firm in Denver.”

The web gives up more valuable data. Using Google Street View, Lotan was able to study the person’s house–a single-family home near a golfing community–and even the car parked outside.

“They blur the license plate [on Google Street View], but you can see what car they drive,” says Lotan.

With more digging online, Lotan filled out the rest of his profile, which included an enthusiasm for hiking, cafes, and the Vista Ridge Community Center in Erie. “On Facebook, you can see everything else, like their kids and a puppy.”

By now, Lotan wasn’t just keeping track of the places this person frequently visited using anonymous smartphone location data: He had managed to crack their entire identity.

If a malicious actor were to obtain this GPS data–collected by any number of smartphone apps, and collected by big companies and startups, advertisers, and law enforcement, with little oversight–they could use it to manipulate or harass that person, or worse.

The Promised Stuff Of The Future

Last fall Lotan taught a class at New York University on surveillance that kicked off with an assignment like the one I’d given him: link anonymous location data with other data sets–from LinkedIn, Facebook, home registration and mortgage records, and other online data.

“It’s not hard to figure out who this [unnamed] person is,” says Lotan. In class, students found that tracking location data around holidays proved to be the easiest way to determine who, exactly, the data belonged to. “Basically,” he says, “visits to private homes that are owned and publicly registered.”

In 2013, researchers at MIT and the Université Catholique de Louvain in Belgium published a paper reporting on 15 months of study of human mobility data for over 1.5 million individuals. What they found is that only four spatio-temporal points are required to “uniquely identify 95% of the individuals.” The researchers concluded that there was very little privacy even in raw location data. Four years later, their calls for policies rectifying concerns about location tracking have fallen largely on deaf ears.

Lotan worries about the availability of the data. “I think something that is important to tell in this story is how many services have access to this information.”

“There are so many apps on an iPhone that run in the background and persistently track your location. They tell you that, but most people don’t know.”

Some apps do it even when you’ve specifically denied them access (see Accuweather); some have stopped tracking you when you’re not using them but only after user protest (see, recently, Uber). (And see the bottom of the story for tips on how to protect yourself.)

For instance, says Lotan, even a company like Foursquare–which is premised on users declaring their real-world locations–is tracking locations in ways the average user doesn’t realize. In the latest of its marketing partnerships–its cash cow–the New York company has teamed up with Pandora to see if the music streaming service’s advertisers, like Subway and Mohegan Sun casino, are getting patronage by tracking the store visits and foot traffic of 2.5 million users who have left their location-sharing feature on at all times.

“[Foursquare] gets that information and actually uses it in a really interesting way, like making predictions of sales of new iPhones when it launches based on foot traffic,” says Lotan.

Facebook, which has been doing location-based advertising for years, recently took this one step further, letting brands target people with ads if they set foot in one of the brands’ real-world stores, and even if they weren’t using Facebook at the time of their visit. The technique mixes Facebook, web, and location data with transaction data from the brands themselves and other third parties.

“A juice shop, for example, could target Facebook users who came in for a smoothie the week before with a coupon code for the next time they visit, while a bookstore could automatically display an ad with the latest titles to people who made a purchase within the last month,” according to AdExchanger, an ad industry site.

Google has also been fortifying its location data arsenal, determining, for instance, whether its ads lead to real-world visits and purchases. (To do so it relies on databases said to cover 70% of all U.S. credit and debit card transactions.) Snapchat is also making a play for better location tracking: In June it purchased Placed, a “location analytics” startup that they hope will prove ads lead to both foot traffic and purchases. This kind of location data could effectively involve the digital companies in many of our real-world purchases.

Data brokers like Axciom–which are unknown, invisible forces to most of the people they profile (i.e., everyone they can)–work with sites like Facebook to collect and deal all sorts of personal offline data. They and others aspire to collect data about your education level, estimated net worth, recent purchases, religious and political views, and habits, among other things. The gold mine is connecting this to real-time location information, so that advertisers can grab your attention almost exactly when they need to.

“I’ve talked to a lot of ad tech and marketing people, [and] for them location data is the promised stuff of the future,” says Lotan. “The promise of personalization, segmentation, figuring out how to sell to people based on a better understanding of them. Much more of this is coming, and it’s crazy how much you can understand by looking at this data.”

At South by Southwest, the London Bullion Market Association–a wholesale over-the-counter market for the trading of gold and silver–released a report noting that geo-targeted ad sales, through both location data and Bluetooth-based beacon technology, are expected to rise from $12.4 billion in 2016 to $32.4 billion in 2021.

This July, Apple, which sees itself as a beacon of user privacy, threw a spanner into the location tracking works when it announced that iOS 11 would notify users how and when apps were tracking location in the background with a blue bar overlay at the top of the screen. Apple now demands that developers offer a “While Using the App” option for location tracking control instead of either “Always” (which runs at all times) or “Never,” with Uber being the most notable company to loosen its location tracking as a result.

Browsing on the company’s Safari browser, whether on a smartphone, tablet, or even a laptop, can also lead to location tracking. But Safari’s Location Services allows users to adjust permissions for websites that want to “gather and use information based on the current location” of a user’s device. Meanwhile, Apple’s “Frequent Locations” feature, buried deep in iOS privacy settings, tracks and stores user’s movements and locations, which the company says is designed to improve its map app functionality.

Location data is also ripe for theft. Last year, BeautifulPeople.com, a controversial dating site for “elites,” suffered a massive leak of user profiles. Within this treasure trove of data (then reportedly being sold by data traders in the web’s more shadowy corridors) were the users’ location data. A recent report, published by Canadian nonprofit Open Effect, found that wearables like Fitbit Charge HR, Garmin’s VivoSmart, Jawbone Up 2, and others transmit location data in non-secure ways, leaving them open to man-in-the-middle attacks.

While tech companies–and, by extension, advertisers–have access to user location data because users have given their permission, law enforcement has another way to access it: They can obtain location data directly from the telecom companies through a court order. A case currently pending in the Supreme Court, Carpenter v. United States, will decide if this law needs to be changed, or if a search warrant is necessary to obtain that kind of data. (A number of large tech companies have filed amicus briefs arguing for more stringent controls.)

Anonymizing Is Possible

Despite the proliferation of personal geo data, Eckersley insists anonymization is possible. It would be as if the spaghetti lines are chopped up and reconfigured so as to make it at least impractical to follow any one trip for very long. Eckersley says very few companies are taking these steps or using subtle algorithms to achieve it.

EFF has been trying to raise awareness about this issue for years, but Eckersley says there really isn’t a consistent legal framework for location anonymity in the U.S.

Despite his familiarity with the subject, Lotan says he was surprised by how far he could go simply by spending a few hours on two raw data sets. The data is only going to get more granular, more specific, and more available, he says–good news for Silicon Valley and the advertising industry, but creepy news for a lot of other people.

Lotan’s advice for people who don’t want their location data being used against them? Make sure to truly understand the location sharing on your phone, but also across the various apps being used. “Many apps have location sharing turned on by default even if the app doesn’t really need to use location,” he says.

At the more extreme end, “not owning property and moving around in a dense city makes it much harder to figure out” who you are.

Related: How To Make A Secret Phone Call

Eckersley says maintaining location privacy is possible but extremely difficult with contemporary technologies. He recommends disabling location services on devices when possible and only enabling them for short periods of time for specific purposes, like directions.

More privacy-conscious users could also use a VPN or TOR to access the internet over Wi-Fi, because telecom companies and others can easily convert your computer’s IP address into a street address.

And if you need high location security, “for instance, if you’re going to a protest that’s likely to be heavily surveilled,” says Eckersley, “the only way to truly protect your location is to disable your phone.” Putting it into “airplane mode” is usually sufficient, but removing the battery is “really the only truly reliable option,” he says.

“Clearly, there’s a lot more that device makers would need to do if they wanted to offer real locational privacy options in their products.”

How to Disable Location Tracking

Android Users: To disable location tracking on an Android device, go to Settings. Scroll down and tap Location, then switch the slider to the off position. This, however, will turn off all location tracking so that apps like Google Maps or even Uber or Lyft won’t work. To control location tracking with more granularity, go into each app through the App Manager and turn off location tracking. Android Users can also delete their device’s location history.

iOS Users: Navigate to Settings, then scroll down and tap on Privacy, then tap on Location Services. At this point users can disable location tracking wholesale by toggling the slider to off. Alternatively, this Location Services lists all apps that use location tracking, allowing users to control which apps have access to location and when. Users can either select “Never” or “While Using the App.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.