“Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food.”

Hippocrates may not have actually put it in quite those words, but that slogan summarizes his brand of doctoring. Just eat healthy food, right?

Not so fast. It turns out that the connection between food and health is complicated by two facts discovered in recent decades.

First fact: Diet affects the health of different individuals in different ways. There’s no such thing as a one-size-fits-all diet. Our genetics and other factors such as age and gender determine whether specific foods are good or bad for us. For example, kale is supposed to be good for you. But if you’re genetically predisposed to forming kidney stones, kale is bad for you.

Second fact: A majority of the cells in our bodies are non-human microbes, most of which live in our digestive tract. These microbes affect our immune systems and overall health. The populations and functioning of this microbiota are determined in part by our lifestyles, including diet, pharmaceutical drugs, and other factors.

In other words, the link between diet and health is definitive but massively intricate. While science has made dramatic progress in generally understanding human DNA, human health, and the effects of food on diet, all this knowledge can be hard to turn into healthy actions. What matters is the matching of a specific person’s DNA with specific foods–something called nutrigenomics.

With machine learning and detailed data, it should be possible to combine DNA testing and quantified self-tracking to understand dietary needs and apply this to the “Internet of Food” to satisfy those needs. (I define the Internet of Food as a large-scale effort to enable all known information about every food ingredient and product to be accessible by machines, consumers, and companies.)

This sounds like a new frontier in technology. And in fact, already Silicon Valley and the tech industry are churning out startups that appear to leverage advances in DNA sequencing and other technologies to provide highly personalized diet and lifestyle advice.

The Internet Of Food: Still Incomplete

A startup called Habit is in the news, in part because the company’s sole investor is the Campbell Soup Company. Habit plans to start offering in January kits that test DNA and blood, resulting in personalized nutrition advice–“nutrition recommendations based on an individual’s unique biology, metabolism, and personal goals.” Likewise, companies like LifeNome, Nutrigenomix, PlainSmart, and DNAFit run DNA test results through proprietary algorithms to offer personalized diet and lifestyle advice.

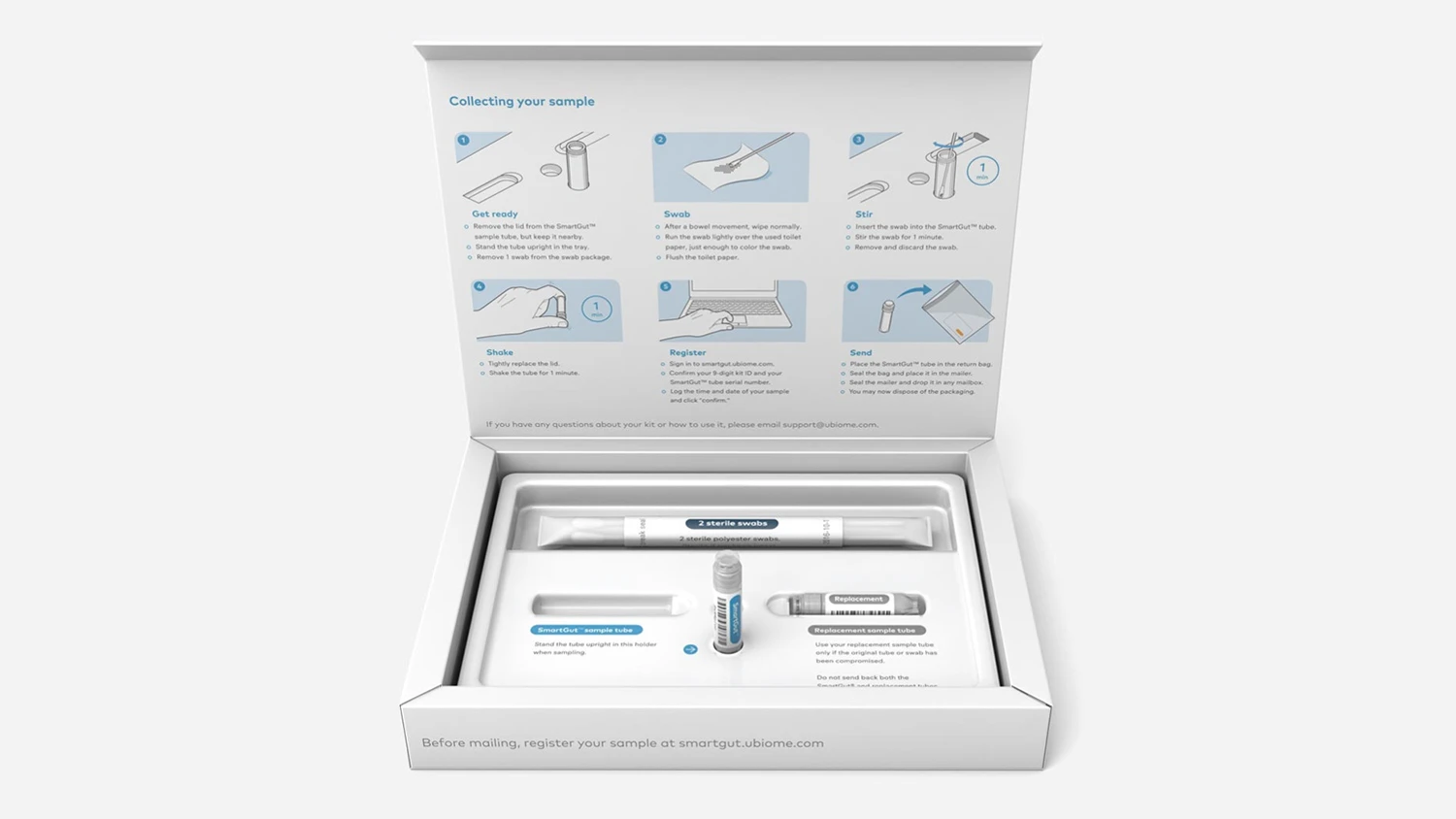

Other companies offer variations on the theme. Vitagene uses DNA and other testing to discover nutritional deficiencies, which are corrected through personalized vitamin and mineral supplements. DayTwo and uBiome test not your DNA, but the DNA of your gut microbes and offer advice based on the results.

DNA tests, as well as more conventional tests like blood tests, can produce data about individual people. But what can we discover about food that we don’t already know?

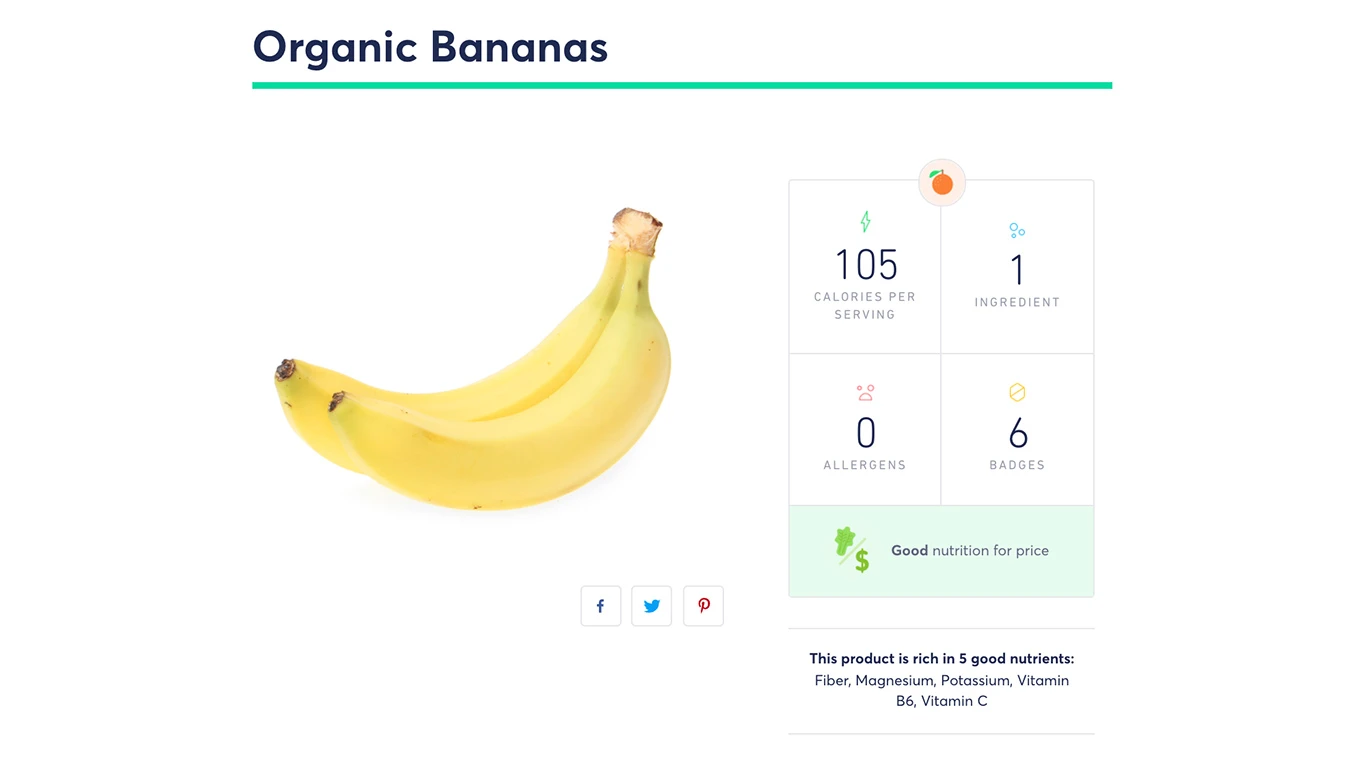

The Internet of Food is an enormous initiative still in its infancy. But we do have databases that talk about food types (apples generally, rather than the specific apple in your hand) and their nutritional content. These include the Sage Project, the Food Wiki, Open Food Facts, and the USDA’s Food Composition Databases.

These kinds of databases give information about food, mostly provided by the companies that produce them. It’s a kind of honor system that’s unable to account for variation in ingredients, sourcing, manufacturing, shipping, storing, and other factors.

Some companies offer detailed advice based on such databases. A company called ph360 makes a virtual assistant named “Shae” that guides you through your day on what to eat and when to exercise. Its advice is based on an extensive questionnaire to determine personal genetic information, plus “100% evidence-based science that’s behind the algorithms” that offer the diet and lifestyle advice, according to ph360 CEO Matt Riemann.

Riemann told me that Shae uses artificial intelligence to learn your preferences and habits. For example, Shae “cross-correlates what you like [to eat] vs. what’s good for you.”

Analyzing The Eats

Without a functioning Internet of Food to refer to, the only way to divine some of the vital data about what we eat is to test the food itself. One company, Clear Labs, performs DNA testing on various foods to figure out if they’re counterfeit or contaminated–or if they contain gluten, heavy metals, allergens, antibiotics, hormones, pesticides, or GMOs.

Other companies provide home testing kits. None of them test for everything; each tends to specialize. For example, a startup called Nima offers a portable device that tests food for gluten. Another company, Tellspec, sells a gadget that roughly estimates calories, carbohydrates, fats, protein, fiber, and glycemic load. MyDx (which stands for “My Diagnostic”) is working on a handheld product called MyDx which, along with a plug-in module sold separately called OrganaDx, tests your actual food for some pesticides and heavy metals. The device can also test water and cannabis.

The real question behind these startups, devices, and services is: Is it really possible to use DNA testing, databases, and sensors to figure out exactly what’s best to eat? Ahmed El-Sohemy, the founder of Nutrigenomix, says that “using the right type of genetic information enables us to provide more specific dietary advice now than what we provided just a few years ago.”

The MyDx analyzer lets you test your own food for pesticides

Nutrigenomics companies can “look at very specific locations in genes that have been studied for their association to nutrition response,” according to DNAFit CEO Avi Lasarow. For example, a so-called vitamin D receptor gene can “influence how well the receptor binds vitamin D, and therefore affect how much vitamin D a person will need for optimal health.”

Other well-defined areas include lactose intolerance, caffeine metabolism and, say, how efficiently an individual can extract calories from food.

Nutrigenomics startups typically examine thousands of “biomarkers” looking for data useful in the personalization of diet and lifestyle. But the result is less exact than you might think. LifeNome cofounder Ali Mostashari says that his company’s genomics analyses results in what he calls a “probabilistic assessment of the unique dietary needs of individuals.”

Today’s understanding of DNA is too limited to rely on DNA testing alone. For starters, geneticists confront something called the “missing heritability problem,” the fact that a big part of genetic effects can’t be explained by the gene mapping we’re able to do. A study published in the journal Nature three years ago suggested that the “missing heritability problem” is really due to inadequate technology.

DNAFit uses a patented algorithm to rank or weight the relative effect of various genetic data points. Such algorithms, which crucially include data from sources like questionnaires, are the main business secret of DNA diet companies. As Lasarow points out, “environmental information must form the base of any kind of lifestyle strategy. These are factors such as age, weight, activity levels, and dietary history.”

Another major environmental factor–probably the biggest one for many people–is the effect of pharmaceutical drugs. Vitagene CEO Mehdi Maghsoodnia told me that many commonly prescribed medications have “a systemic effect on the body,” transforming the microbiome and often causing nutritional deficiencies even months later (Vitagene looks for about 25,000 possible nutritional deficiencies potentially caused by medications alone).

Even food itself is inconsistent and unpredictable, which is why Vitagene emphasizes nutritional deficiencies corrected with pill supplements, rather than dietary advice. “I do not believe that the science is there for us to make a statement about food,” Maghsoodnia told me. “Food itself gets to be very complex.” Food involves not only complex combinations of ingredients, but how we digest it, how it affects the microbiome, and other factors. “We don’t even understand a lot of the detailed chemical processes that happen as food is combined and processed within our body.”

Companies like DayTwo focus on DNA-testing the gut microbiome, in part because it’s much more responsive to changes in diet and lifestyle. DayTwo CEO Lihi Segal says that “as the microbiome may change over time following the implementation of personalized diet, remeasurement of the microbiome over time may be needed to adjust the personal algorithm.”

The Future Of Big Food Data

Not surprisingly, the people who are working on nutrigenomics tend to be universally optimistic about the promise of using DNA testing to optimize individual diets in the years ahead.

The most powerful of these advancements will result from the collection and processing of data and tracking cause-and-effect over time, according to Maghsoodnia: “The human body is complex enough that you won’t find those answers through fundamental research in the short run. You’ll find it through data correlation.”

Mostashari agrees. “The only way we can get there is actually through individuals supporting these scientific advances by providing researchers with more information about their dietary habits and what works and doesn’t,” he says.

The genes themselves tell us nothing about diet or health, directly. “Genomics science today is based on association studies,” says Mostashari. Essentially research starts with groups of people who share the same malady, then see if there’s anything in the genes they all share, but which are not shared by people who do not have the same health issue.

Put another way, more and better data is the key to effective nutrigenomics. Startups have an outsize role to play: These companies are able to track far more correlations between DNA and nutrition, and far more “test subjects” over a longer period of time, than researchers at universities can.

Personalization of the diet extends well beyond genetics alone, Lasarow says: “In the future, dietary strategies will be based on a combination of an individual’s genetics, microbiome, biomarkers, and environmental factors to create completely bespoke advice.” And the future of the quantified-self movement has a big role to play.

Rather than relying on questionnaires to figure out each person’s activity level, sleep habits, air quality, and other factors, wearable sensors will fill in these blanks automatically.

Best of all, according to Lasarow, this data will increasingly take on a real-time aspect, with constant monitoring, sensing, and testing. This should account for not only changes over time but also the constant metabolic changes that occur in the body throughout the day to help the optimization of overall health.

Mostashari makes a bold prediction: “I believe within the next five years we will see this transition to become a mainstream aspect of nutrition and dieting.” In 10 years, he expects that “high-fidelity nutrition personalization will be a norm rather than an outlier.”

In fact, combining genetic tests with the Internet of Food could result in diets so precisely and beneficially targeted that it could replace for many people the mainstays of today’s medicine–drugs and surgery. “Dietary intake could be customized to a degree that ideally would reduce the incidence of widespread diseases like cardiovascular disease, which is largely influenced by diet,” according to El-Sohemy. And he points to another benefit: improved public scientific literacy around food. Instead of relying on marketing hype around whether foods are “good for you” or “bad for you,” consumers could know what’s actually in their food and how it affects them, personally.

The promise of nutrigenomics is nothing less than the full realization of Hippocrates’ vision. With vastly better data generated by DNA and other testing and real-time quantified-self technology, as well as the Internet of Food and food-sensor devices, we should be able to individually tailor and optimize diet in a way that improves health without drugs or surgery for millions of people.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.