Everyone has an Ikea horror story. My wife’s work desk, for instance, took her and my mother-in-law an entire day to assemble, moving forward only in fits and starts with frequent intermissions for cursing. (I’d have helped, but I was conveniently absent for reasons I can’t recall.) Even Ikea itself seems to have accepted this reputation. “A newspaper in Sweden described Ikea [furniture assembly] as something between civil engineering and captaining a submarine, and I think that’s a good description,” says Allan Dickner, Ikea’s deputy packaging manager.

Still, there’s one foolproof method for turning Ikea rage into grudging respect: assembling almost any other brand of furniture. After an hour spent comparing piles of ambiguous components against an assembly diagram that looked like a misfiled mimeograph from Area 51, I somehow produced a HomeGoods end table—as well as a surging curiosity about how Ikea designs its own packaging and instructions, which now seemed positively Eamesian in comparison. To adapt Winston Churchill’s famous quip, Ikea may be the worst form of ready-to-assemble product design we have—except for all the others.

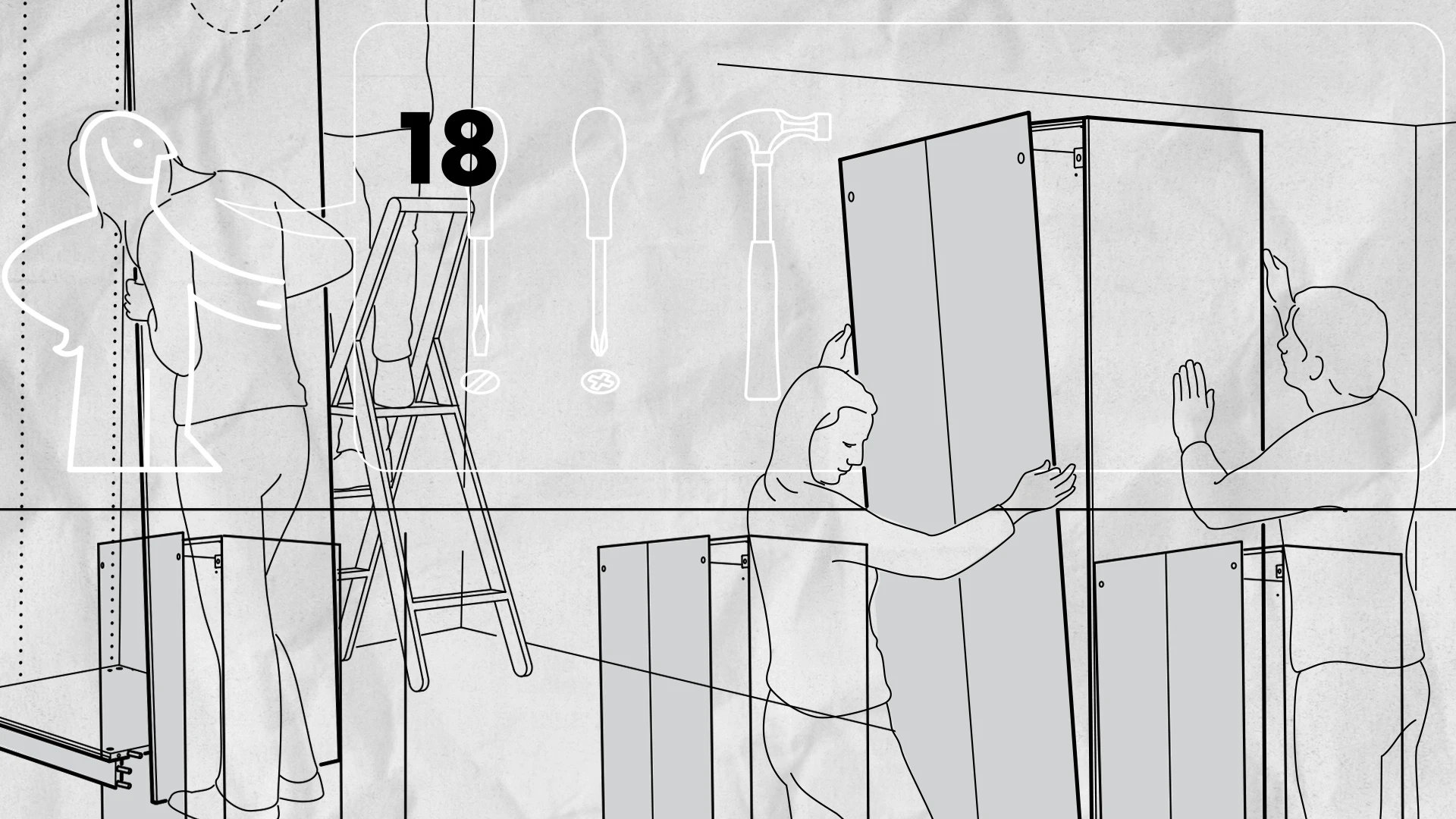

According to Allan Dickner, whatever your most frustrating Ikea experience is, it could have been worse—and most likely was for the packaging engineer who test-assembled even more complicated versions of the product before arriving at the optimized design that you unboxed on your living room floor. “We had one furniture piece, a type of wardrobe, which originally had over 400 fittings and screws to hold it together,” Dickner says.

Of course, this extreme “knock-down”—the industry term for disassembly of products to make them easier and cheaper to ship to customers—is a big reason why that Ikea wardrobe is so affordable. “But when it takes someone five hours to build it, you can ask yourself: have you gone too far with the flat packing?” Dickner adds. “It’s always about finding a balance between ease of assembly and optimizing the packaging.” (That wardrobe, for the record, was redesigned to “knock down” into fewer components.)

Ikea’s flat-packaging engineers are included alongside product designers in the initial briefings for any new Ikea offering. But after a half-century of knocking down bookshelves and armoires, Ikea doesn’t need to reinvent the wheel very often. For 80% of ready-to-assemble products, Ikea packaging engineers rely on what Dickner calls “proven solutions”: generalized templates that the engineer nips and tucks to match the specifications of a new item.

These proven solutions aren’t just algorithmically optimized (although they are that)—they also incorporate on-the-ground knowledge about living conditions in all the countries where Ikea furniture is sold. “It would be quite stupid to design a package that’s flat and efficient but won’t fit into a small elevator or staircase,” Dickner explains. “It sounds ridiculous, but in the United Kingdom, that was one of the most frequent reasons for a customer returning a product.” He adds that global package designs are tested in Japan and South Korea “because those are the customers who live in the smallest spaces.”

Turning a three-dimensional sofa into a pseudo 2-D flat-packed jigsaw puzzle is no mean design feat. But if the assembly instructions don’t make sense, all that work is moot. According to Jan Fredlund, an designer who works on these instruction booklets, there are two guiding principles behind every page: clarity and continuity.

The first term is obvious enough, but Ikea takes it seriously enough that instruction designers (or “communicators,” according to Fredlund) start by putting a product together themselves. “Test assembly provides an opportunity to find out if there is a risk that the customer might place a certain part in the wrong direction which may not look like an obvious mistake in the moment, but will cause a problem many steps later,” Fredlund says.

Continuity, meanwhile, is what separates Ikea’s instructions—even the maddening ones—from those of other brands. The Lego-like, frame-by-frame illustrations are based on construction drawings, digital snapshots, 3-D models, and videos of test assemblies. Designers take pains to render each successive picture from a single, unchanging point-of-view (mimicking that of the customer), so that confusing rotations or perspective changes are minimized and the customer can stay oriented more easily as he or she moves back and forth between the booklet and the parts.

If the end result does sometimes feel like a civil engineering project (as Dickner admits with some pride), it’s because a high level of precision and redundancy is exactly what undergirds even the most complex or tedious Ikea assemblies. They may not be pleasant, but they are at least rational and comprehensible—even sympathetic—by design. Think of that big-nosed “Ikea man” who’s shown calling the company when he gets stuck. He’s not mocking or condescending. If anything, he represents some designer at Ikea who has already gone through exactly what you’re going through now on your living room floor: half-quizzically glancing from instruction booklet to pile-of-parts and back, hoping for the best, but trusting that it will all, at the very least, make sense.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.