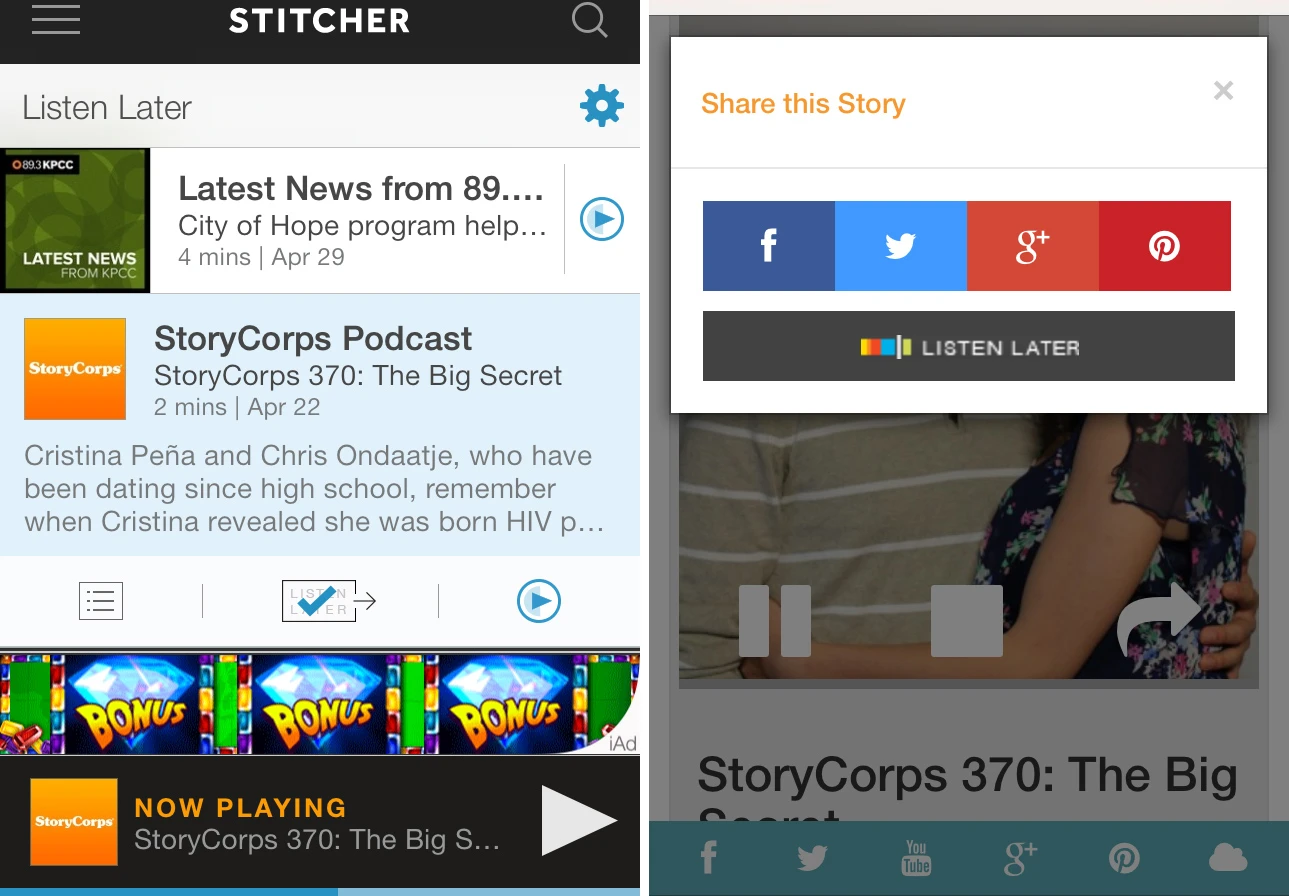

Starting today online audio has a new button: “Listen Later.”

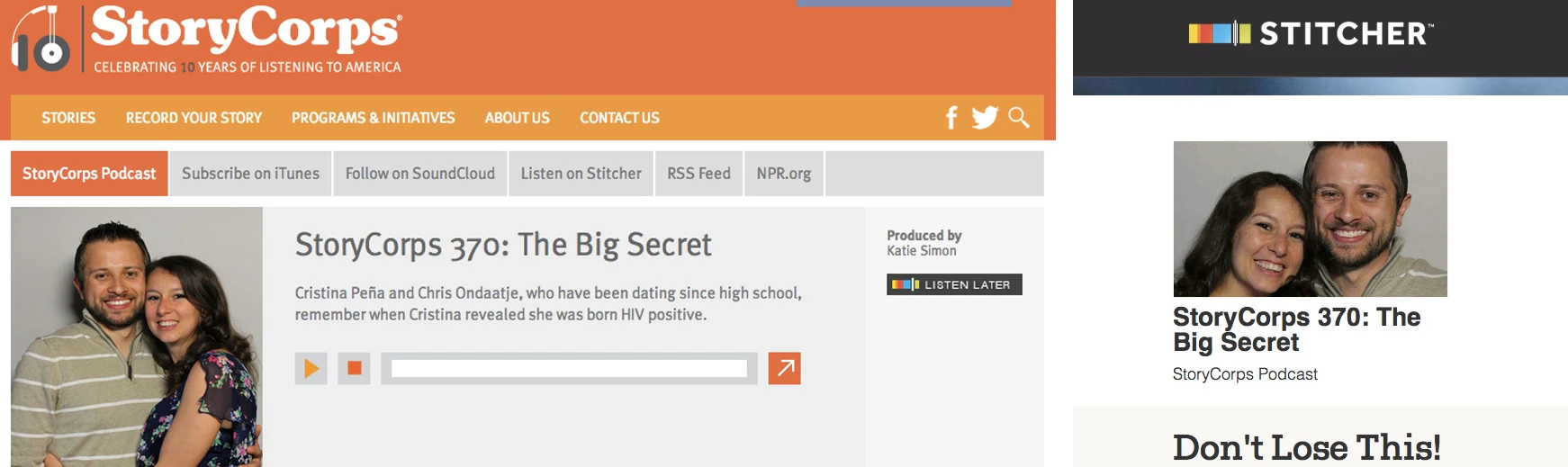

It’s part of a pilot project hatched over the last few months by on-demand radio app Stitcher, now operational on just a handful of websites in the podcast and radio world: the Financial Times, Fox News, Science Friday, StoryCorps, Smodcast Network, and Heritage Radio.

But Stitcher intends to spread it across their network of more than 20,000 shows as a better way to knit together the frenetic pecking we do on the web with the continuous attention we muster offline to make sense of the spoken word. Click the button, close the page, and when you open the Stitcher app, a “Listen Later” playlist will contain all the audio you bookmarked.

For Stitcher, it’s a play for more listeners. When it comes to digital listening to spoken word audio, Stitcher claims to be in second place only to the podcast downloads that happen through iTunes. But it’s a distant second; Stitcher doesn’t disclose figures but has been installed on only 1% of smartphones, according to Edison Research. “Listen Later” aims to convert some of the other 99% by offering something that Apple hasn’t, and that individual shows can’t: An app that seamlessly unites individual segments with an app that can stream them. “The RSS system [used for podcast subscriptions] is kind of antiquated,” says Stitcher CEO and cofounder Noah Shanok. “If we can make it as easy to consume as the radio–you know, press the button and go–then it’s going to bridge the gap to mainstream.”

The question is whether their approach can work–and whether enough mainstream users really want it.

“An Instapaper for audio”

The easiest way to describe the “Listen Later” project is that it attempts to do for spoken word audio what read-it-later apps like Instapaper and Pocket have done for text. “An Instapaper for audio? That’s exactly what it is,” says Shanok.

Instapaper and Pocket are services for those who encounter an article they want to save–not forever, but long enough to actually read. “We have said for many years that our biggest competitor is people who still email themselves links,” says Pocket CEO and founder Nate Weiner.

Their advantage over email is a service with two sides. On the one hand: an easy way to bookmark, through the click of a button added to both web browsers and platforms like Twitter. On the other: an easy way to read the bookmarked items, with an interface that renders all articles in a consistent, becalmed interface of black and white text, and places them in a single, downloadable queue.

The simple concept has become only more important as the various screens we interact with have multiplied, and the value proposition has become not just “read it later” but “read it on your smartphone or tablet.” Of the billion items saved since Pocket began in 2007, half have come in the last 12 months. “So you can see how quickly we’re ramping up,” Weiner says.

As they’ve grown, both Pocket and Instapaper have expanded their focus from text to incorporate a variety of web pages and a growing segment of video. “We’d really like Instapaper to be a place where you can save any kind of content, ranging from the Amazon URL to Wikipedia and everything in between,” says the company’s general manager, Brian Donohue. Only a bare majority of 55% of saves on Pocket are what the company classifies as “articles.”

But neither Instapaper nor Pocket has made any real attempt to capture audio. The best either can do is save the URL of a website, browse back to it later and click play–hardly a step up from emailing a link. “We don’t really see much audio [being saved],” says Donohue. “But we don’t really handle audio very well.”

This is why the small niche of online audio fans have long pined for just such an “Instapaper for audio.” Media reporters called the concept a “killer app” and claimed, more dramatically: “Whoever solves this problem wins at web audio.”

Overcoming an Oxymoron

The problem is, essentially, that “web audio” is usually an oxymoron. “Listening takes place generally while you’re not looking at your computer, when you’re body’s captive to something like cooking dinner or driving but your mind is free,” notes Stitcher’s Shanok. “So the browse mode and the consume mode are two very different modes.”

If you’re browsing your Facebook feed and find a five-minute radio segment, shifting it to a mobile playlist typically means downloading and transferring the file, or bookmarking the URL and browsing back later. If the audio is a podcast, the process involves subscribing to the show and then hunting its archives to find the appropriate episode. “It’s just a huge pain in the ass,” says Shanok.

Even more than with text articles, Stitcher needs not only to make it easy to save, but to make it easy to consume.

For proof, consider Ethan Zuckerman. He commutes for more than three hours–in each direction–from his home in Lanesborough to Cambridge, Massachusetts where he directs MIT’s Civic Media Center. He walks for an additional hour a day. “I try to fill some of the time with phone calls,” he says, “but a lot of it gets filled with podcasts.” They allow for choice, but a choice among subscriptions, which means his listening diet is ultimately as limited as any radio dial. “I’ve come up with an extremely diverse lineup, but I’m predictably channeled into the nine or 10 things that I listen to,” Zuckerman says. “When I periodically encounter audio I want to listen to, instead of having to download it onto a desktop, I would love to just click something and have it show up for my walk the next day.”

But while this sounds like exactly the problem Stitcher aims to solve, Stitcher’s solution comes with weaknesses of its own. Stitcher has made it very easy to consume any audio that you save; but the audio you can save is inherently limited. Stitcher doesn’t take the open web for its library; it’s a directory of shows with which it has direct relationships (including nearly every major show distributed on podcast). Stitcher’s “Listen Later,” then, is less of an “Instapaper for audio” and more a “Pocket for podcasts”–or, more accurately, for those podcasts that agree to put a Stitcher-branded button on their websites. Even if all of Stitcher’s more than 20,000 partners sign on, it will leave out the one-off recordings, the amateurs outside the podcast universe, the lectures on YouTube: all the stuff that Zuckerman wants. “It’s not that I have anything against the pro content department, but at the end of the day, I want something as universal as possible,” he says.

The Past Is Prologue?

A more universal “Listen Later” service has been attempted before.

Three years ago, Irish web developer Eoin Hennessey began work on what would become Later.fm: A web application with a button for your browser that is actually labeled “Listen Later.” It was born out of Hennessey’s desire to keep a running playlist of songs from music blogs like Pitchfork, as his habits shifted from downloading files to streaming services like SoundCloud and Rdio. He thought the process would be easy. “Just stick ‘em in a queue; put a play, pause, skip button on there; you’re done,” he laughs. “Not really the case.”

He was following in the footsteps of another Irish web developer, Jeremy Keith, who three years prior began work on HuffDuffer. It’s a similar concept to Later.fm, but with an explicit focus on capturing radio segments and podcast episodes, and presenting the results not in a continuous playlist but in a podcast. (It was invented, after all, in 2008, during podcasting’s post-iPhone second wave.)

Both of them follow, more closely even than Stitcher, the model laid down by the likes of Instapaper and Pocket. They operate primarily through a clickable “bookmarklet” button added to a web browser; they attempt to take as their domain all audio on the web; they suck up the chaos of any given webpage and algorithmically distill it into something that can meaningfully be served up in a simple, mobile-ready template.

“The service has to go to that URL and figure out what is what,” says Keith. “What’s the title here? Are there tags I can pull out? Where does the content begin and end?”

“The difference is that whereas on Instapaper you want to grab the content–the actual text–and pull that down onto your phone, with HuffDuffer it’s always just a link to the audio file.” The same could be said for Later.fm: “It doesn’t actually grab audio files, it just points to them.”

It’s a small distinction with large ramifications, technical and legal. Technically speaking, it saves Later.fm and HuffDuffer the hassle of scraping and hosting files, which could be prohibitive for revenue-free side projects. (Audio files are smaller than video, but still significantly larger than text; if only Silicon Valley’s Pied Piper was real.) Legally, it steers clear of the copyright claims that could be invoked if they were actually creating copies of files–a risk that is a heavier cloud when it comes to streaming audio and video than it is for text. “I don’t see anyone moving into that territory of saving streaming content and caching it offline,” says Instapaper’s Donohue. “I think it’s just a really legally gray area that no one wants to venture into.”

For HuffDuffer, the trade-off is that the archives are littered with broken links, and on websites where a link to the audio file isn’t available–think SoundCloud and players built using Flash–the system breaks down entirely. For Later.fm, the major hang-up has been in getting those streaming to services to cooperate; Hennessey hasn’t been able to complete a mobile app, and a version that transmutes the SoundCloud streams into podcast downloads has yet to be made public. “It’s something I plan on running by SoundCloud before releasing it,” he says. “I’ve actually got no idea how they’ll feel about it.” (SoundCloud didn’t respond to an emailed question on this topic.)

Stitcher, in contrast, doesn’t have to worry about dead links, copyright, template-shattering web design or competing platforms’ APIs and Terms of Service. “Listen Later” links will only exist where Stitcher has not only permission but control, usually going as far as hosting the audio. “It can’t be hacky,” says Shanok. “It has to be really good.”

Ease of use is what Stitcher is relying on to win over both listeners and shows.

In the immediate near-term, Stitcher says its list of “Listen Later” partners will grow to include Time.com, NPR’s Planet Money, The Moth, and American Public Media (home of Marketplace, where, full disclosure, I often work as a radio reporter). But to expand it will have to convince the rest that a “Listen Later” link shouldn’t add audio to a playlist on their own website (as many currently do), or on their own app–a particular concern for content behemoths like NPR.

“There could potentially be resistance,” admits Shanok. (NPR’s new mobile app, currently in beta, doesn’t have any such feature, though when asked about the possibility in a Facebook group for mobile testers, creative technologist Jeremy Penbrook wrote: “It’s certainly something we’re interested in looking at.”)

Even among the current partners, there’s a certain amount of “wait and see.” You can “Listen Later” to StoryCorps’ podcasts, but not the individual stories. “I do think we will go down that route potentially in the future,” says StoryCorps director of web and information technology Dean Haddock. “But I want to see, and we want to see in the organization, how this might affect our podcast numbers.”

If there are more listeners, it will be easier to convince more shows; if there are more shows, it will be easier to convince more listeners. “There’s a little bit of chicken and egg to it,” says Shanok. “You need to enable it in enough places, that it sort of becomes pervasive.”

A Youth Movement

The highest hurdle to becoming pervasive may be the plethora of social networks and platforms where audio is encountered on the web. SoundCloud, for instance, has little incentive to help users “Listen Later” on a competing service. (SoundCloud did not respond to an emailed question on this topic, either.) Where gaps exist, the analogy with Pocket or Instapaper breaks down. “People don’t want multiple Pockets,” says Pocket’s CEO, Weiner. “They don’t want to have to remember, ‘Did I see that thing on Twitter? Or did I see that thing on my browser?’”

But Shanok’s hope is that a button on the website of a growing slate of popular shows will be enough to win some of the 85% of the population who don’t listen to podcasts–specifically some of those under the age of 24. “The percentage [of Stitcher users] represented by that younger group is on a trend of growth at about 5% each month,” says Shanok.

“If they’re looking for audio content, they’re not going to look on the radio,” he says. “They’re going to look online.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the final deadline, June 7.

Sign up for Brands That Matter notifications here.