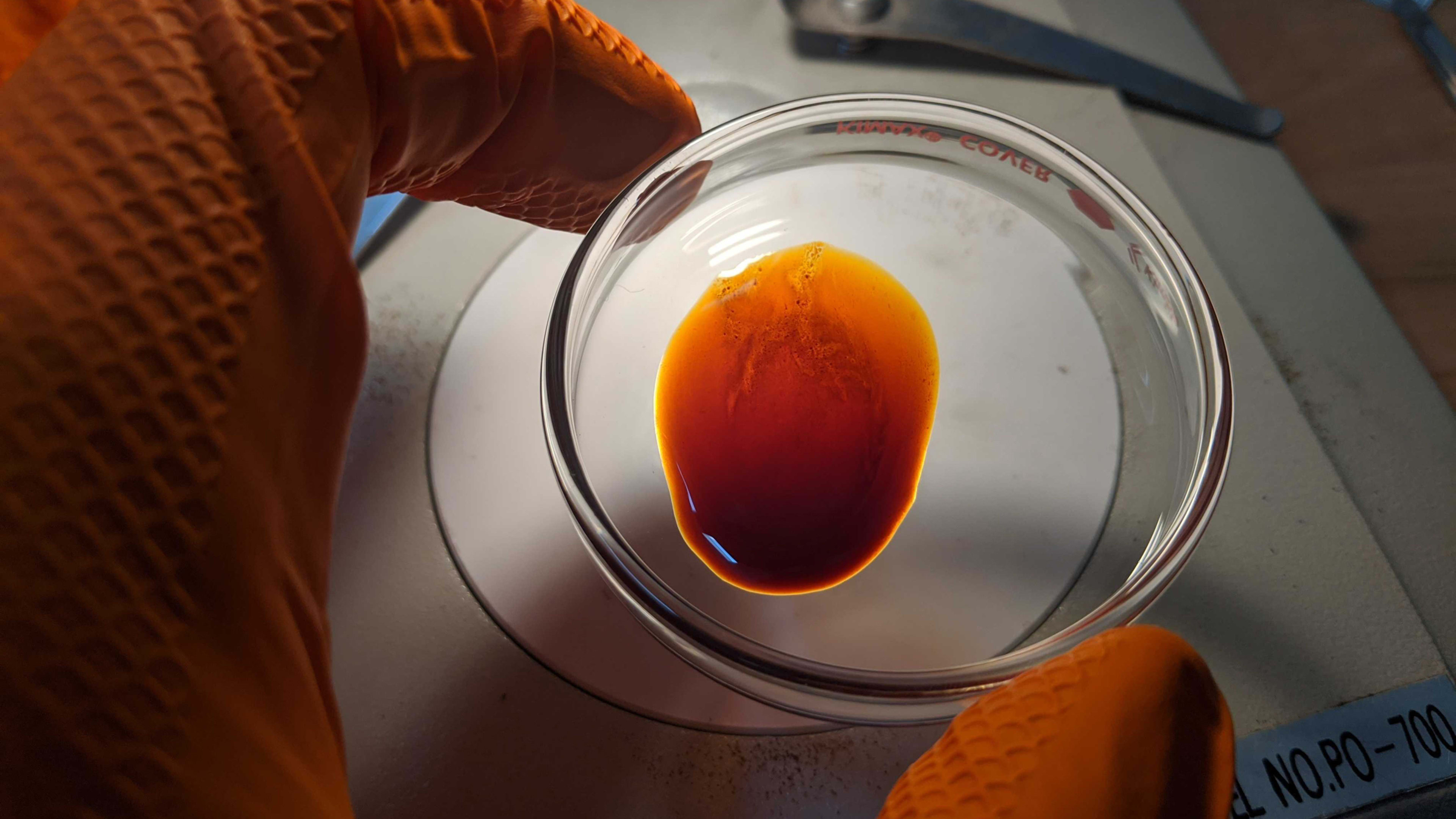

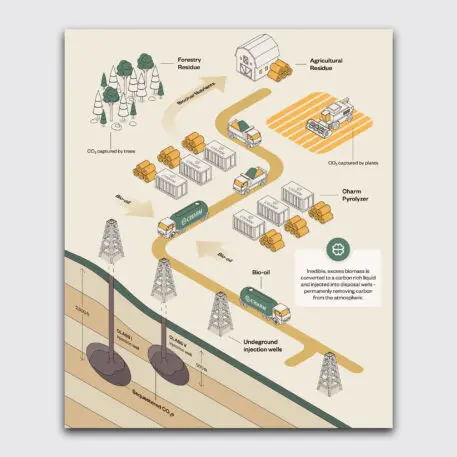

Two years ago, a tiny startup called Charm Industrial pioneered a new business model: turning agricultural waste into “bio-oil,” a dark, gloopy liquid that can be injected underground to sequester the carbon captured by the plants. Then it sells its carbon removal service to companies that want permanent offsets for their emissions.

By the end of 2021, months after it began operating, the startup had stored more than 5,000 tons of CO2 underground, the largest permanent carbon removal that had ever happened. Now, the company has a new deal with Frontier—a coalition of companies that want to support the nascent carbon removal industry—to spend $53 million on its services, removing 112,000 tons of CO2 by the end of the decade.

While the process is expensive now, at around $600 per ton of capture CO2, “we think that Charm has a feasible path to low-cost carbon removal at scale,” says Nan Ransohoff, head of climate at the tech company Stripe, which first began working with early-stage carbon removal startups internally, and then cofounded Frontier last year, along with Alphabet, Shopify, Meta, and McKinsey.

The deal is the first in a series of the group’s “offtake” agreements, legally-binding commitments to buy carbon removal services at a certain volume and price. Each company it considers goes through a vetting process with a group of scientists on staff, with input from an advisory board of another 50 technical experts.

To avoid the worst impacts from climate change, society needs to steeply cut emissions and remove CO2 from the air, both to deal with emissions that can’t immediately be eliminated and to begin to tackle all of the pollution that’s already in the atmosphere. As much as 10 billion metric tons of CO2 may need to be pulled from the air every year by the middle of the century.

Right now, most carbon removal happens in nature. But carbon captured in a forest can easily be lost if drought kills trees or there’s a wildfire; it’s also difficult to accurately measure and track natural carbon storage. And we’ll eventually run out of land to plant new trees at the scale that’s needed. So, companies like Stripe have been searching for other solutions, including capturing CO2 in rocks or through new technology in the ocean.

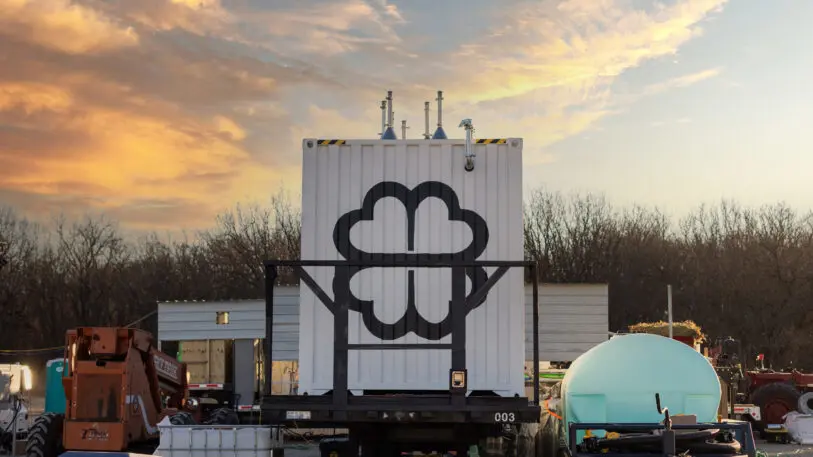

Charm Industrial’s approach makes use of nature, as plants capture carbon through photosynthesis, but then also uses pyrolizers, equipment that can heat up the biomass and turn it into a bio-oil. When the oil is injected at an old oil or gas well, it sinks down and solidifies into place. The company is currently working on mobile pyrolizers that can travel to farm fields and work on site to transform plant waste, like corn stover, left behind after crops are harvested. The waste would normally release CO2 and methane as it decomposes. “That happens on a pretty quick timescale—almost all of it has rotted and returned to the atmosphere in about three years,” says Charm CEO and cofounder Peter Reinhardt. There are around 2 million old wells that can be used to store the bio-oil.

The price of Charm’s process is expected to drop 37% between 2024 and 2030 as the process becomes more efficient and the startup can begin operating at a larger scale. It could drop as much 75% if government incentives for carbon removal begin to include Charm’s new approach.

Frontier also supports even earlier-stage startups with “pre-purchase” checks of $500,000 to help them pilot their technology. “The purpose of Frontier was to send a really loud demand signal to entrepreneurs and founders that if they build a promising solution, there will be buyers for it,” says Ransohoff. Already, she says, they’re seeing many more startups enter the space. The offtake agreements, for larger dollar amounts, are designed to help companies go from early prototypes to a larger scale.

Charm Industrial’s approach is one of many that the group plans to support. “Our belief is that to get to the roughly 5 billion tonnes of removal that the world needs every year by 2050, we are going to need a portfolio of solutions,” says Ransohoff. “The volumes we’re talking about here are just so massive that most pathways have will max out at a certain size. So, we’ll have to aggregate them together.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.