Among the many challenges people living with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) face is its impact on their speech. By weakening muscles in the throat and mouth, the progressive disease makes speaking increasingly difficult and lessens the ability to talk clearly and at a typical pace. Most patients contend with these symptoms and ultimately lose the ability to speak at all.

When talking for oneself becomes an issue, speech synthesis is an essential communication tool, whether for chatting with family and friends or just ordering a coffee at a café. For years, people with ALS have been able to plan for this eventuality by creating a digitized version of their own voice, a process known as voice banking. But while voice banking is best done before ALS has affected someone’s speech too much, it’s been daunting, sometimes costly, and tempting to postpone.

Four years ago, when Philip Green banked his voice, he had to record 1,500 phrases for training purposes, an arduous task that took him weeks to complete. So, he understands why others might avoid confronting it.

“To be honest, you have a lot more things on your mind than, ‘Oh, I should invest time in preserving a version of my voice that I may need in two years or six months or four years,'” says Green, a member of the board of directors at Team Gleason, a nonprofit that serves those with ALS. “You’re really not thinking about that. But what we are trying to do is make people aware. Do it as soon as you find out [your diagnosis], because it’s essentially an insurance policy that you hope you won’t have to use.”

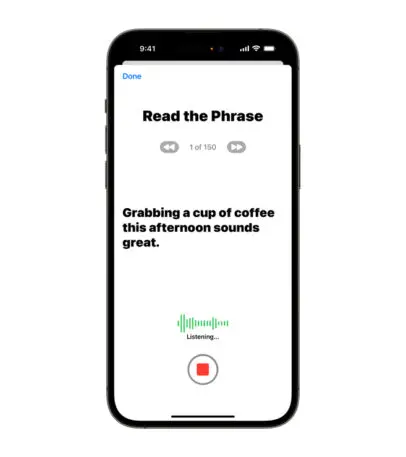

Starting soon, people will be able to easily create and use a digitized version of their own voice using an approachable piece of equipment they already own: an iPhone, iPad, or Mac. That’s thanks to Personal Voice, a new accessibility feature Apple plans to ship later this year. It needs only 15 minutes of spoken phrases for training—which users can break into multiple recording sessions if they choose—and does all processing locally. The voices it produces work in Apple’s own apps as well as third-party augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) apps from companies such as AssistiveWare.

Apple says that any Mac based on Apple silicon will support the creation of Personal Voices; it hasn’t yet disclosed which iPhone and iPad models will. The feature leverages the company’s Neural Engine technology, which optimizes dedicated computing cores in its processors for artificial intelligence. The initial processing is a demanding enough job that users may want to leave it chugging away on their device while it charges overnight. But in the morning, their digitized voice should be ready for use.

Though Personal Voice wouldn’t be possible without recent advances in AI and the ever-increasing computational muscle of Apple’s chips, the enabling tech is only part of the story. Apple Senior Director of Global Accessibility Policy and Initiatives Sarah Herrlinger is quick to emphasize that company worked closely with members of the ALS community to implement the feature in a way that met their needs, from the purely practical to the cultural. Among those who contributed insights were Green and others at Team Gleason, which was founded by former New Orleans Saints player Steve Gleason, along with his wife Michel, after he was diagnosed with ALS in 2011.

“One of the core tenets of how we do our work is that commitment to the disability mantra of ‘Nothing about us without us,'” says Herrlinger, a 20-year Apple veteran. “It is pivotal to our work to not design for communities, but to design with them. And so working with individuals like the folks at Team Gleason really gives us deeper knowledge of the daily experiences of people who live with ALS.”

Personal Voice is one of several upcoming features that Apple announced this week to mark today’s 12th annual Global Accessibility Awareness Day. A related one, Live Speech, lets users type to generate synthesized speech in apps such as FaceTime and for in-person conversations. Detection Mode allows those who are blind or have low vision to point their phone’s camera at text-based interfaces they encounter—such as a microwave oven’s buttons—to facilitate navigation. And Assistive Access streamlines the most popular iPhone and iPad features for easier use by people with cognitive disabilities.

‘I wish I voice-banked sooner’

After being diagnosed with ALS, Brooke Eby, a sales executive at Salesforce, took to Instagram and TikTok to share her journey, educate others about ALS, and generally get the world more comfortable talking about the disease and its implications for those who have it. Talking to others in the community, “I constantly hear, ‘I wish I voice-banked sooner,'” she says. “Some people, all of a sudden, will just start slurring their words, and then it’s almost too late to voice bank. They’re like, ‘Never mind, this doesn’t sound like me anyway, so I might just well just use a [generic] robot voice.'”

View this post on Instagram

When it’s possible for people to use a voice that sounds like themselves, it can be a deeply meaningful part of the experience. “I want my family to hear my synthetic voice and not think that I’m a robot,” explains Green. “But that I’m the same person that I was prior to my diagnosis.”

For Apple, making each user’s Personal Voice truly personal required rethinking the whole notion of what a digital voice should sound like. After all, Siri may talk in a variety of voices these days, but they’re all pleasantly anodyne, and that’s a pro rather than a con. In real life, by contrast, our unique way of speaking reflects a lot about who we are. Apple wanted to capture as much of that individualism as possible.

Historically, that’s been a tough aspiration for a voice-banking technology to achieve. “The solutions that currently exist don’t take in accent, tone, inflection, cadence,” says Team Gleason Executive Director Blair Casey. “And what Apple’s been working on diligently and behind the scenes is an accurate representation of identity through voice.”

People who create Personal Voices will get to judge for themselves how well the company met this goal. With audio samples I heard, reproducing a variety of distinct voices, the intonation and pacing could be a bit flat, as computerized speech tends to be. Overall, though, they were impressive, entirely distinct from each other, and certainly worlds apart from the one-voice-fits-all feel of most of the synthesized speech in our lives.

Personal—and private

As critical as vocal fidelity was, it wasn’t the sole overriding factor Apple had to consider while designing the Personal Voice feature. “Along with accessibility being one of our core corporate values, so is privacy, and we don’t believe that one should have to give up one to get another,” says Herrlinger. Indeed, it’s tough to imagine a more sensitive personal piece of data than a replica of someone’s own voice, which meant that the company had to give users confidence that theirs couldn’t wind up in anybody else’s hands.

Generating each Personal Voice on an iPhone, iPad, or Mac lets users take advantage of the feature without uploading any of the associated data to the cloud at all. Those creating voices for later use will presumably want to sync them to their iCloud account for eventual access on devices they may not yet own. But that process only happens at their express instruction, and the data is encrypted on Apple’s servers.

When it came to enabling third-party apps to speak via Personal Voice, Apple put privacy measures in place similar to those it imposes for photos, location, and other bits of personal data in its care. Such apps can only hook into Personal Voice with the user’s permission, must be running in the foreground, and receive only enough access to read text in the voice, not to get at the data used to generate it.

Since 2018, people with ALS have been able to take advantage of a Team Gleason program that covers the cost of voice banking. By building the technology into its products in such an Apple-esque way, Apple is making it even more accessible to “the person that’s diagnosed tomorrow or next year,” says Green. Unlike the subsidy, Personal Voice is also available to users outside the U.S.; Team Gleason Executive Director Casey calls it “a stepping stone to what’s next.” (The app will support only English at launch.)

For Apple, Personal Voice and the other features it unveiled this week are tangible proof of its dedication to accessibility—an initiative that Herrlinger points out began with the company’s first office of disability back in 1985, five years before the Americans with Disabilities Act became law. But rather claiming all the credit for Apple, she turns much of it over to the ALS community. It was talking to the kinds of people who may use Personal Voice that made Apple realize “that our technology is uniquely positioned to be able to solve problems like this in ways that others may not even be thinking about,” she says.

As with many a new Apple idea before it, we’ll know that Personal Voice has succeeded if it becomes a perfectly normal everyday reality—at least for the folks whose lives it has so much potential to improve.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.