In 2014, a man named Billy Raymond Counterman began sending a string of creepy Facebook messages to a female musician he’d never met. “You’re not being good for human relations. Die. Don’t need you,” read one.

“I’m currently unsupervised. I know, it freaks me out too, but the possibilities are endless,” read another.

Some of the messages suggested the target, a singer-songwriter who’s referred to as C.W. in court documents, was being watched. Others made vague, confusing references to phone lines being tapped. When C.W. blocked Counterman’s account, more messages would appear from new accounts in a pattern that persisted for two frightening years. Counterman was eventually arrested in 2016 and charged with violating Colorado’s anti-stalking statute. A jury found him guilty and sentenced him to four and a half years in prison.

On Wednesday, the Supreme Court will consider whether the lower courts got it right in a case that could have sweeping consequences not just for victims of cyberstalking but for online speech writ large.

The question before the court in this case, Counterman v. Colorado, is whether Counterman’s many messages are protected by the First Amendment or whether they constitute “true threats.” The Court has held for decades that true threats are not protected speech, but legal scholars are divided as to the precise definition of what constitutes a true threat.

Through the appeals process, Counterman’s side has argued that because it was not his intent to threaten C.W., his statements were not, in fact, true threats. “[C]ourts have always required a guilty mind even to punish violent conduct—which, unlike speech, does not receive First Amendment protection,” Counterman’s legal team wrote in their Supreme Court brief.

The state of Colorado, meanwhile, has argued that it’s the circumstances in which the message is sent and received—not the speaker’s mental state—that matters. “Threats have long fallen outside the First Amendment because they injure those threatened no matter what the person making the threat had in mind,” the state wrote in its brief.

The case has drawn a flurry of responses from all corners, including civil liberties advocates, First Amendment scholars, press freedom organizations, and others, who are deeply split as far as how the court should rule.

On one side are groups like the Electronic Frontier Foundation and the American Civil Liberties Union, who argue that if the Court decides a speaker’s intent doesn’t matter in determining what is and isn’t a true threat, it could risk opening people up to criminal prosecution for a broad swath of speech. That’s particularly true online, given how little control people have over where their public social media posts wind up, argues David Greene, senior staff attorney at the EFF.

“We want to make sure that people, when they speak, have some idea about and can anticipate whether or not they’re going to be punished for their words,” says Greene, who coauthored the EFF’s amicus brief.

On the other side are civil rights activists and legal scholars who fear that if a speaker’s intent is all that matters, then victims will have no recourse to stop stalkers and harassers who are merely delusional.

“Stalking uniquely is one of those situations where the more deluded the person is, the more dangerous they are, and to give them basically a free pass because they’re deluded would really have catastrophic consequences,” says Mary Anne Franks, president of the Cyber Civil Rights Initiative, which works to protect victims of online abuse. Franks coauthored a brief to the court siding with the state of Colorado.

This is not the first time the Supreme Court has taken up the question of how to treat threats made on social media. In a similar case in 2014, the court overwhelmingly voted in favor of a man named Anthony Elonis, who was sentenced to prison for a series of public Facebook posts, which, among other things, contained violent lyrics targeting his ex-wife. In the majority opinion, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote, “Wrongdoing must be conscious to be criminal.”

But the court’s ruling in that case was narrow, and ducked the First Amendment question presented in Counterman entirely. Now, it seems, the justices are hoping to address the issue of true threats head-on.

The problem is, as some legal scholars have pointed out, Counterman’s case is a pretty messy way to do that. What Counterman was convicted of was stalking, not making threats. The two offenses may overlap, but there are key differences between them in the eyes of the law. True threats are, in essence, speech. Stalking is conduct. Even if Counterman never uttered a threatening word, his relentless pattern of sending private communications targeting a specific, unwilling victim would still be punishable as stalking, argues Evelyn Douek, assistant professor of law at Stanford Law School, who coauthored a brief to the court with two other First Amendment scholars.

“We are perplexed and frustrated and amazed that this case has been so successfully recast as a threats case,” Douek says, noting that the question of what is or isn’t a threat arose through Counterman’s appeals process.

Right now, there are anti-stalking statutes all across the country, including in Colorado and at the federal level, that prohibit stalking behavior—things like repeatedly following, contacting, or surveilling someone in a way that would cause a reasonable person distress. Many of these laws say nothing about whether the stalker ever even makes a threat.

“Stalking statutes were passed in response to the fact that these stalkers commit this harm, and very often they don’t make explicit threats,” Douek says.

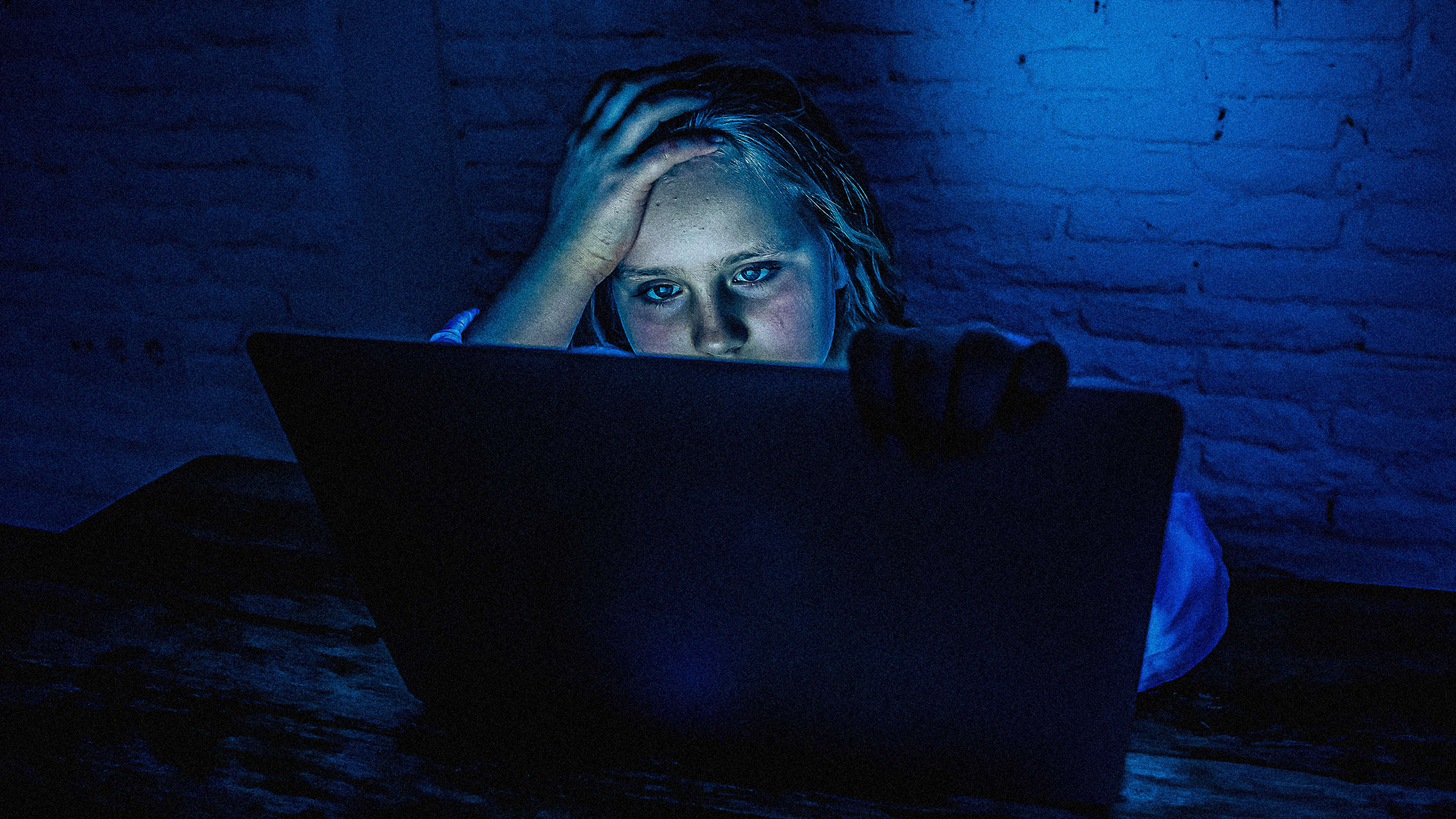

Offline, stalking may mean surveilling someone at their home or showing up at their office. But online, cyberstalking often implicates speech, making it an already tricky category of crime to police.

If the court were to side with Counterman, Douek says, it could undermine all of those laws, making a crime that is already difficult to prosecute even harder to police. “We are in a world where this kind of conduct is already not taken seriously enough,” Douek says. “To undermine the weak protection that already exists would be very scary.”

Still, Douek acknowledges that the state of Colorado is fighting an “uphill battle,” considering the way the question has been framed around speech—not stalking. She’s hoping that the court is able to grapple with the question of what constitutes a true threat while also explicitly recognizing that stalking is a different issue. “Our goal is to get a footnote,” she says.

Franks of the Cyber Civil Rights Institute is also concerned that, given the court’s ruling in the earlier Elonis case, the justices may be amenable to Counterman’s argument. But she argues that the risk to free speech posed by Counterman’s case is overstated. Colorado’s anti-stalking statute and others like it intentionally set a high bar for what is considered stalking to avoid the possibility that one-off statements and misinterpretations could be considered crimes.

“Colorado’s law doesn’t say ‘All that matters is objectively terrifying conduct or expression.’ It also has to look at the totality of the circumstances,” Franks says. “The world that Counterman is painting is if you have the Colorado standard, there’s going to be this overzealous prosecution of stalking, when the world that we live in is one where we just don’t do anything about stalking until it’s too late.”

Franks pointed out that after Elonis won his case before the Supreme Court, he began stalking his ex-wife, the prosecutor in the case, and his ex-girlfriend. Last month, he was convicted of cyberstalking and sentenced to more than 12 years in prison. “It really is important to think about the implications of making these kinds of people into free speech heroes,” Franks says.

Free speech advocates like Greene understand these concerns. It’s not that Counterman should walk, he says. It’s that Colorado used “the wrong doctrine”—the true threats doctrine—to justify its actions against him. Now that this is the question before the court, Greene says, there are steep costs to siding with Colorado. The Court’s decision regarding what is and isn’t a threat will ultimately apply to all speakers, not just stalkers.

“I really hope we don’t have free speech jurisprudence where we all live in a system where we’ve made restrictions on everybody’s speech to account for the delusional,” he says.

Recognize your brand's excellence by applying to this year's Brands That Matters Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.