Philadelphia prides itself on being a union town. Those roots go deep; back in 1835, it was the site of the first general strike in American history. Uriah Stephens and a handful of other local garment cutters founded the Knights of Labor, the nation’s first industrial labor organization, in 1869. Nearly two centuries later, the city has played host to every kind of labor action, from the birth of influential unions like the American Federation of Full-Fashioned Hosiery Workers to innumerable strikes and protests across every industry imaginable.

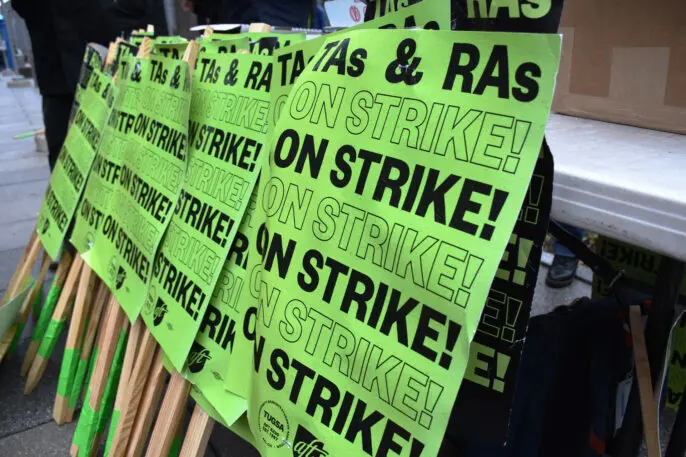

However, the most recent high-profile battle between Philadelphia workers and their employers did not play out on the docks, in the stockyard, or in a factory. Instead, it saw 750 graduate teaching assistants and research assistants at Temple University, one of the city’s finest institutions of higher education, take on their own school’s administration in a historic six-week strike.

The Temple University Graduate Students’ Association (TUGSA) strike—the first strike in the union’s 20-year history at the school—began on January 31, 2023, and became a major story in Philadelphia, attracting support from other union members and labor activists as well as local politicians and community leaders. It even earned the workers a nod from Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, who dinged the university administration for quibbling over workers’ wage demands while paying its football coach millions.

In spite of all the public support, the fight quickly turned ugly. One week into the strike, the university sent out a letter to striking workers informing them that it would be canceling their healthcare and tuition remission (a setup in which the school covers their tuition costs in exchange for them taking on teaching or research assistant roles). The strikers would have had to pay the full cost for their spring semester by March 9, which added an increased sense of urgency to the negotiations. It’s worth noting that Temple’s endowment is valued at $873 million, and the grad student workers’ primary economic demand was a base wage of $32,800.

As well-endowed universities have become increasingly reliant on their low-cost labor, many graduate student workers around the country struggle to make ends meet.

Working as an adjunct or research assistant is a high-stress, poorly-paid gig that comes with a heavy workload and precarious employment status; a 2020 report from the American Federation of Teachers found that nearly 25% of adjunct faculty members rely on public assistance to get by, and 40% have difficulty covering basic household expenses. Many take on courses at multiple schools or add on side jobs to supplement their meager income, which adds more stress to an untenable situation further compounded by the fact that a great number of grad students are also juggling student debt.

Is it any wonder that they’ve started to organize?

TUGSA members had rejected a previous tentative agreement on February 18, but on March 10, the union announced that it had reached a second tentative agreement with the university, one that included “material gains on every major issue.” Three days later, following a membership vote, the new four-year contact was accepted with 98% approval.

“This new contract is a first step toward the university recognizing the value of our work,” Bethany Kosmicki, a member of the union’s negotiating team and past TUGSA president, told The Philadelphia Inquirer. “I feel like the collective power and strength that our union had throughout this strike really sent the message that we needed a fair contract and we were going to be out here until Temple gave us one.”

By walking out and fighting back, the TUGSA workers had also tapped into an ongoing wave of labor actions among workers in higher education, regionally as well as nationwide. The massive University of California graduate student workers’ strike that ended in January 2022 was the largest academic workers’ strike in U.S. history (and the biggest strike of all of 2022), and saw 48,000 workers at 10 campuses across the state hold the line for five weeks.

Higher education has continued to be a hotbed of union activity, and many of the workers leading the charge have similar demands—livable wages, better healthcare benefits, and improved working conditions.

It’s been an uphill battle for many. Graduate student workers at the University of Chicago have been fighting for the past 15 years to win their union, and on March 17 they voted overwhelmingly to join the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America (UE). In January, their counterparts at Northwestern University had done the same, and on the coast, graduate student workers at Yale University voted to join Unite Here Local 33 after decades of organizing. Earlier in March, the Duke Graduate Students Union (DGSU) filed for an election with the National Labor Relations Board, signaling their intent to become the first recognized graduate student union at a private university in the South.

In response, Duke administrators have decided to challenge the 2016 NLRB ruling that recognized grad student workers’ right to unionize (and was originally filed by the Graduate Workers of Columbia-GWC in response to their own school’s pushback against the union). As Chris Simmons, Duke University’s interim VP for public affairs and government relations, said in a statement, “Duke will seek to present evidence demonstrating that its graduate students in their academic programs are not employees, and that the NLRB’s 2016 reasoning was incorrect.”

In order to win its case, Duke will need to jump through multiple legal hoops, starting with the NLRB’s own appeals process and potentially ending up all the way at the federal level (which could take years). “When 45,000 graduate student workers across the country are organizing at this moment, Duke is trying to assert that we don’t have the right to do that—and by extension, neither do any of them,” Anita Simha, cochair of the Duke Graduate Students Union, told WUNC.

If the union is successful in fending off Duke’s challenge, it will not only be a victory for workers in higher ed. “This is a historic moment beyond Durham, too; when we win, we’ll be the biggest union victory in North Carolina since 2008,” Simha wrote in an essay for The Nation.

So many of the graduate student workers who have been fighting—and winning—union recognition over the past several years have chosen to affiliate with established unions like the United Auto Workers, Unite Here, SEIU, and UE (the latter represents grad student workers at the University of New Mexico, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and, as of February, Johns Hopkins), which did not start out as havens for academic workers but have rapidly expanded their efforts to bring them into the fold.

Meanwhile, back in the tristate area, educators at the New Brunswick, New Jersey, campus of another major university, Rutgers, have been watching the Temple strike closely. They just signaled their own willingness to hit the bricks, following up nine months of contentious bargaining sessions with a strike authorization vote that saw 94% of Rutgers AAUP-AFT and Rutgers Adjunct Faculty Union members vote yes. If they do take that step, it would mark the first educators’ strike in the university’s 257-year history. Negotiations are continuing for now, but it’s clear that academic workers at Rutgers are ready and willing to do what so many others in their position have done recently—to make a little history of their own if needed.

Kim Kelly is an independent journalist, author, and organizer whose writing on labor, politics, class, and culture has appeared in Teen Vogue, Rolling Stone, The Nation, The New York Times, The Washington Post, Columbia Journalism Review, and many other publications. Her first book, Fight Like Hell: The Untold History of American Labor, is out now via One Signal/Simon & Schuster. She is currently working on her second book.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.