Experts and leaders will soon come together in the thousands at the first UN conference dedicated to water in nearly half a century.

At the conference, which begins March 22 in New York, delegates will no doubt stress that “water is life.” And it’s true: Water nourishes, cleanses, and even inspires the poetry and painting so desperately needed by our modern and rushed society. We really cannot live without it.

But as a professor of water security who focuses on its role in conflict, I know that water is death too. And I don’t just mean the awesome destructive force of floods—hundreds of children in Pakistan and twice as many adults drowned when a “monsoon on steroids” burst the banks of the Indus River last summer—or agonizing spells of drought.

I mean the way we use water in war—or more specifically, as a tool toward violent political or military objectives, when water becomes a tactical weapon and a strategic battlefield resource. At the UN conference, delegates have a chance to begin to put a stop to this. But before we change our behavior, we must first reflect on it.

Water the weapon

We have for centuries used rivers to hurt our enemies. Back in the early 1500s, Leonardo da Vinci worked with Niccolò Machiavelli on an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to divert the Arno River away from Florence’s rival city, Pisa.

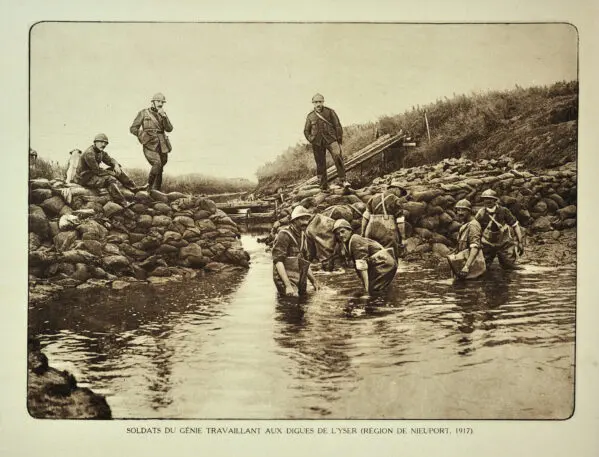

Four centuries later, Belgian teenage troops and farmers knew exactly how to flood the parts of the Yser river that German troops had advanced along during the First World War. Another century after that, Ukrainian forces cut the sole water supply to Crimea after Russia annexed it, and just a few weeks ago Russian troops used the Dnipro river to stop troop advances.

Rivers are also often used to conceal crimes. Paris police threw dozens of their Algerian victims into the Seine in 1961, while Syrian forces dumped dozens of people they had executed into the Aleppo river in 2013, and into the Al Assi in 2015. Sudanese authorities tossed at least 40 of their own people into the Nile in their failed attempt to disrupt protests in 2019—in a way, emulating the British slaughter of 13,000 Sudanese at the confluence of the Blue and White Niles in Omdurman in 1898.

Snipers know the tactical value of water too. They sat several floors up in Sarajevo’s abandoned buildings in the 1990s, perched like patient storks over the women and children who would risk their lives to get to the tap stand at the end of an alley. Snipers also hid behind their scopes at a distance from a leaky pipe in a refugee camp in Beirut in the 1970s, “as if hunting thirsty gazelles” in the words of poet Mahmoud Darwish. “Killer water,” he concludes.

And water can be used more strategically—to clear the killing fields. Dozens of public reservoirs were pierced like colanders in southern Lebanon in 2006, presumably to keep those who had fled to Beirut away. Similarly, elders who refused to flee the fighting in villages in 1990s Kosovo were regularly dumped into backyard wells, to discourage their adult children from returning.

A different type of cleansing also happens along the West Bank of the Jordan River, where Israeli governments provide water to settlers but employ both bureaucratic and physical ways to deny it to the locals. Here, water policy has mixed with political and military goals to the point where they are virtually indistinguishable.

However, water isn’t always an effective tool of military and political violence. For instance, the enormous British “dambusters” campaign in the Second World War, in which dams were targeted with “bouncing bombs,” is disingenuously remembered. In fact, it only managed to properly take out two dams in the end, and killed mostly Russian women civilian prisoners of war who had been forced to work in German factories along the Ruhr river. More recently, the Islamic State discovered that control of a dam in Iraq and Syria does not automatically give you control of the people who live downstream.

The battle for water—and ourselves

Though humanity uses water to nurture, it also uses water to destroy and to contaminate, or to ethnically cleanse territory even as water is made the foundation of global public health. For all its wonderful properties, water is a critical mirror of society. It exposes the extent to which we are led by ideologies and greed, and juxtaposes some of the world’s most inspiring and depraved behavior.

But now, people are fighting back. Lawyers are developing principles on the protection of the environment and water infrastructure during armed conflict. If we muster the will and courage, these initiatives can feed into relevant security council resolutions, maybe even a UN Convention. Eventually, the tactical use of water could be as unacceptable as using human shields or targeting schools.

The battle to stop the abuse of water will not be won or lost at the UN conference in New York. But if fought well, it will reflect kindly on us all.

Mark Zeitoun is a professor of water security at the University of East Anglia.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.