The New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) is the nation’s largest landlord of public housing, which also means it has the potential to be the nation’s largest slumlord. By its own accounting, NYCHA’s 177,000-apartment portfolio is dilapidated to the tune of $40 billion. This deferred maintenance on things like elevators, heaters, and air-conditioning makes life challenging for many residents and operation of the vast system a perplexing headache.

In the face of these challenges, a potential solution has come from an unlikely source. In a speculative design proposal, New York-based architecture firm Peterson Rich Office has offered a refreshingly practical approach to creating solutions that might actually make a difference in the lived experience of residents.

The New York-based firm has narrowed in on a persistent problem: the failing and often under-maintained steam-based radiator heating found in many of the postwar public housing buildings operated by NYCHA. Peterson Rich Office has proposed solving this problem by adding more efficient and more easily maintained electric HVAC units to apartments within the system. To hold those units, and to provide outdoor space to residents, the architects proposed tacking structures onto the sides of these public housing towers, creating scaffolds for the heating and cooling units and balconies for the people living there. “It kind of kills two birds with one stone,” says Nathan Rich, cofounder of Peterson Rich Office.

The project is included in a new exhibition now open at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Architecture Now: New Publics, New York, which focuses on architecture firms that are designing for different facets of the public realm. Peterson Rich Office’s design, which also includes a broader vision to build more housing and resident amenities on NYCHA’s large land holdings, is the kind of well-meaning design that museumgoers will likely nod at approvingly while lamenting how it will likely never get built.

And yet, kernels of this thinking are making their way into actual NYCHA housing projects, and showing that even speculative design can begin to change the way the status quo looks and operates.

Peterson Rich Office’s design proposal grew out of several years’ worth of investigation into NYCHA’s buildings and land holdings, the classic towers-in-the-park approach to public housing that was replicated in cities around the country after World War II. By studying the buildings and their challenges, which range from the broken heaters and other deferred maintenance to bleak landscaping and systemic underfunding, the architects came to understand that the problems NYCHA faced required more than just good design. They needed across-the-board livability improvements.

Rich says there’s hope that this is now being made possible through a recent change to the way public housing operates in New York City. NYCHA launched a program in 2017 called Permanent Affordability Commitment Together, or PACT, that puts some of its buildings under the management of private landlords through lease agreements. Still considered affordable housing, the new management structure changes the way federal funding is applied to these buildings, and opens the possibility for landlords and property managers to borrow against the value of the land—financing that can support improvements to building maintenance, infrastructure, and public spaces. It’s the kind of funding needed to support the two-birds-one-stone type of design ideas developed by Peterson Rich Office.

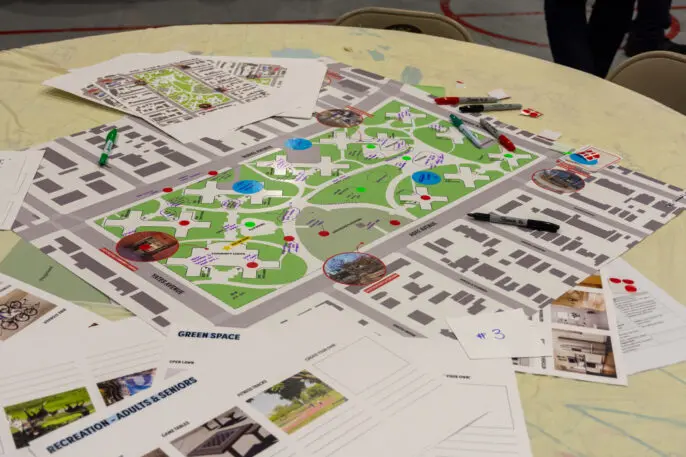

The firm is now working directly with NYCHA on 16 of the housing projects in the PACT program, leading public outreach efforts and community design meetings to understand the day-to-day issues of most concern at each housing project and the longer term potentials of their buildings and land.

“It’s an experiment,” Rich says. “People get nervous when they hear about private entities on the public side, or the privatization of public housing. It’s a public private partnership and in general so far it’s shown to be very successful.”

One project, at the 984-unit Rangel Houses in Upper Manhattan, is in the midst of a planning process that Rich says is leading to large improvements to the green spaces surrounding the project’s eight buildings. Feedback from residents helped the designers understand that there was need for more diverse public spaces throughout, with activities geared towards people across the age spectrum, not just the playground set. And with the site located directly on the Harlem River, plans are being made to turn its river edge into a flood resilient landscape that protects the buildings while offering new outdoor activities.

Rich says that compared to the ideas presented in the MoMA show, this work is slightly less ambitious. But it’s still showing the potential for new thinking about housing developments long seen as too dysfunctional to repair.

It’s also a replicable approach beyond New York, says Rich. “A lot of the public housing authorities nationwide were built on these same planning principles,” he says. Many are aging and at risk of demolition, if they haven’t been torn down already. Finding new financing mechanisms can help address the deferred maintenance issued and energy efficiency challenges of buildings that are 60 to 70 years old, while also improving resident amenities. Without this kind of intervention, many of these public housing structures could soon be deemed unlivable and torn down. “In some cases there might be cause for that, but it’s not the sustainable thing to do,” says Rich. “When there’s opportunity to do an adaptive reuse of these existing buildings, I think it’s the more responsible approach.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.