What is art when it’s not ideated from a human mind or fleshed into being by a human hand?

It’s a question that’s roiled industry stakeholders and armchair intellectuals for the past few years, ever since generative AI splashed onto the scene. Can AI-drawn shades of color and twists of shape or line evoke the same emotion as those that flowed forth from the fingertips of, say, Vincent van Gogh, at his yellow house in southern France, the wild hallucinations of a man whose psychological turmoil was so great that he sliced off a piece of his own ear? Can those works of art, devoid of human invention, inspire the same flights of fancy as those of Claude Monet, who planted water lily gardens to see the world through more romantic eyes?

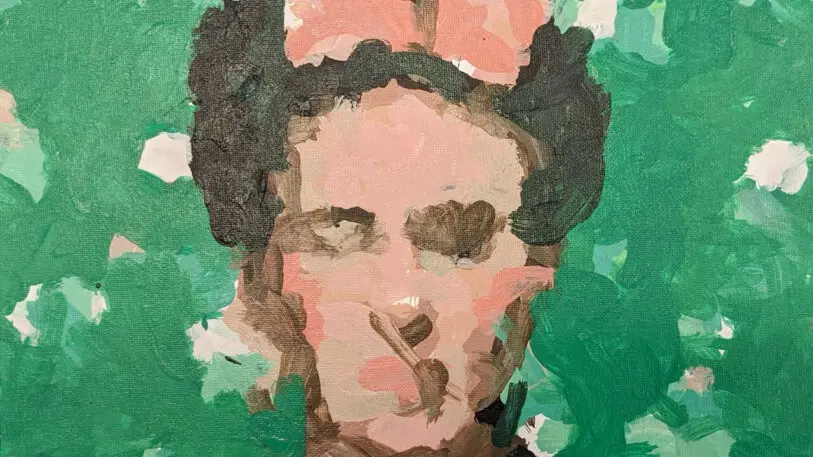

Take this oil painting of Frida Kahlo, created in a studio at Carnegie Mellon University. The image came from neither human mind nor human hand. Rather, it was a product of FRIDA, a robot with a mechanical arm that can dip brushes in water, dab them in paint palettes, and then dash the colors onto a canvas, forming pictures that look either childish or like the scribblings of a savant—depending on how generously you interpret it.

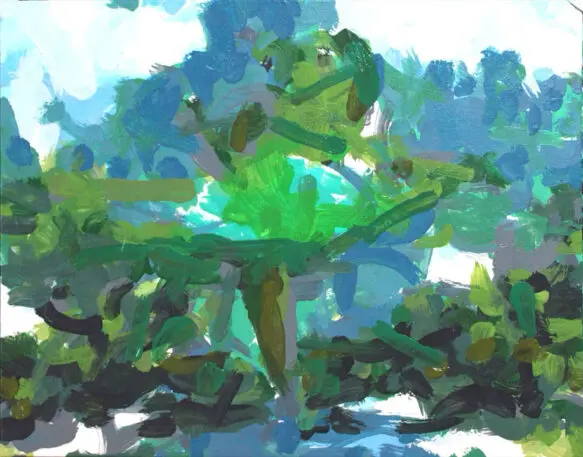

“There’s this one painting of a frog ballerina that I think turned out really nicely,” Peter Schaldenbrand, a doctoral student at Carnegie Mellon’s school of computer science, said in a video showcasing FRIDA. “It’s subtle, but once you get it . . . “

FRIDA is a brainchild of the university’s Robotics Institute. It’s named after the famous Mexican painter, but it’s also an acronym for “Framework and Robotics Initiative for Developing Arts.” It uses machine learning similar to OpenAI’s DALL-E or GPT to generate images in response to a prompt from a human. But FRIDA goes one step further by manifesting those images in the physical world—with real pigment on paper, rather than pixels on a computer.

“People have very high-level ideas about what kind of things they want to paint,” Jean Oh, an associate professor at the Robotics Institute, said in the video. “But few people actually have a concrete idea of what the fine art artifact would be. But they start with some semantic goals.”

So if you’ve ever had the vague wisps of a fantastic vision grace your brain—perhaps, a Dante’s Inferno-esque apocalyptic wormhole rendered in the cubist style of Pablo Picasso (what would that look like?)—you could feed that prompt to FRIDA and then await your dream; realized.

The prompt could be even more abstract: In trials, developers played the audio of ABBA’s pop song “Dancing Queen” for FRIDA and asked it to paint that scene. FRIDA produces these masterpieces in a given number of brush strokes: more for a spectacularly detailed painting, or less for a minimalist aesthetic. However, it does have its limitations—it can’t mix paints, but it can tell you exactly how much to blend in order to make the palettes it needs. (According to Carnegie Mellon, the university’s architecture and machine learning schools are at work on an automatic paint mixer.)

Despite the exacting science that it must take to program a robot with all of FRIDA’s functions, its developers say the imprecision at the heart of painting—which is, in a nutshell, a discipline of streaking and smudging pigments with a small bundle of weasel’s hair—can breathe life into the machine. If FRIDA makes a mistake, like dragging the brush with too much intensity or dripping a random blot on the canvas, it embraces the error, and its algorithmic designs morph to reflect the reality of the image.

In this way, developers say FRIDA might grasp at bottling the indescribable beauty of human art—that is, its perennially imperfect nature.

But FRIDA can’t do it alone. And the team at Carnegie Mellon stresses that it’s meant to work with humans—to be the flourish to their creativity. “People wonder if FRIDA is going to take artists’ jobs, but the main goal of the FRIDA project is quite the opposite,” said Oh. “I personally wanted to be an artist. Now I can actually collaborate with FRIDA to express my ideas in painting.”

But finally—back to the burning question at the very beginning of this story. What does art mean to us? FRIDA’s developers don’t have the answers. But Jim McCann, an assistant professor at the Robotics Institute, has some thoughts.

“You could be very reductionist and say, ‘Artistic expression is this mysterious thing that we don’t understand. We do understand how FRIDA works. It’s juggling numbers in tables, and those numbers were derived from large collections of images and words, therefore, there can’t be any room for artistic expression,'” McCann said on video. “But, we could turn this around and say, ‘Well, what does an artist do but distill some subset of the zeitgeist—of what people around them are saying and doing—and turn that into an expression?’ That’s exactly what FRIDA is doing.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.