What’s in a name?

If Juliet (that Juliet) was right, naming things wouldn’t change what they really are, and a rose, “by any other name, would smell as sweet.” Except the human brain is wired to draw connections between ideas, names and feelings. Shakespeare knew it, expecting parents know it, and every single corporate brand in history knows it.

“Naming as a discipline is one of most difficult things that companies do,” says Pentagram’s Michael Bierut. As a partner at one the world’s most influential design agencies, Bierut is deeply familiar with the practice of naming things, but the practice of naming cars in particular has fascinated him ever since he stumbled upon a letter correspondence between a 1950s Ford executive and a poet.

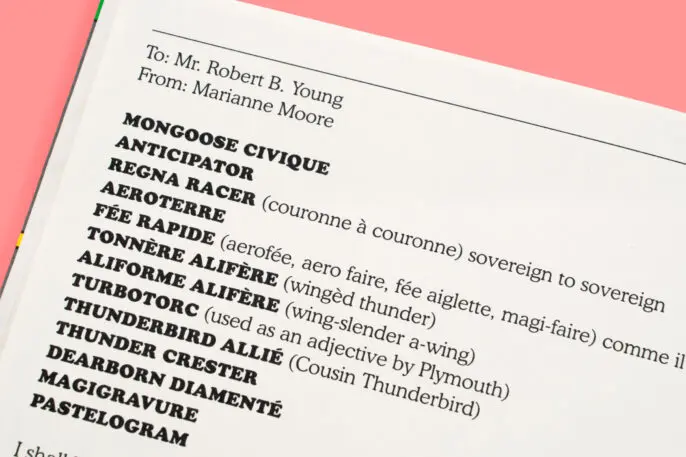

The story goes like this: In 1955, Ford Motor Company asked the Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Marianne Moore to help it name the first new car it had produced in decades—one they had spent 10 years and $250 million on planning. Ford’s marketing research team had cycled through three hundred names of “embarrassing pedestrianism” and was now looking for a name that “flashes a dramatically desirable picture in people’s minds.” Over a series of letters between Moore and a Ford executive named Robert B. Young, the poet submitted more than two dozen names, from “Ford Fabergé” to “Utopian Turtletop,” only in the end for the company to name the car after Henry Ford’s son, Edsel. “It was a monumental flop,” says Bierut.

The fascinating story is now relayed in Pentagram’s latest annual holiday card. Yes, it’s a month late, but the booklet is less of a holiday card than it is a charming homage to a little-known morsel of cultural history that remains highly relevant today. (A limited quantity will be available upon request to anyone who sends proof of donation to the Alliance for Young Artists & Writers.)

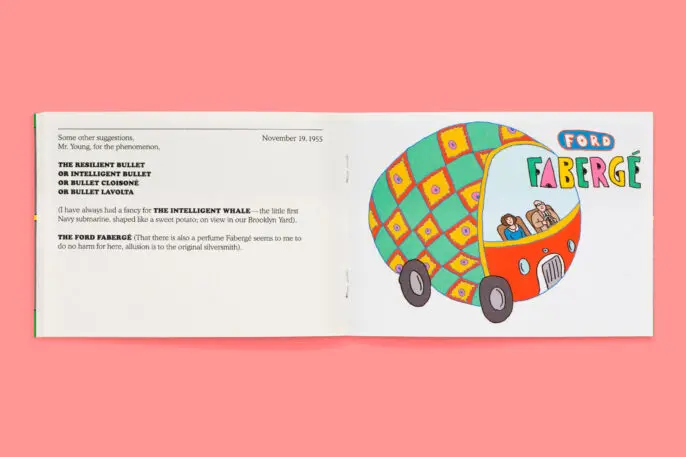

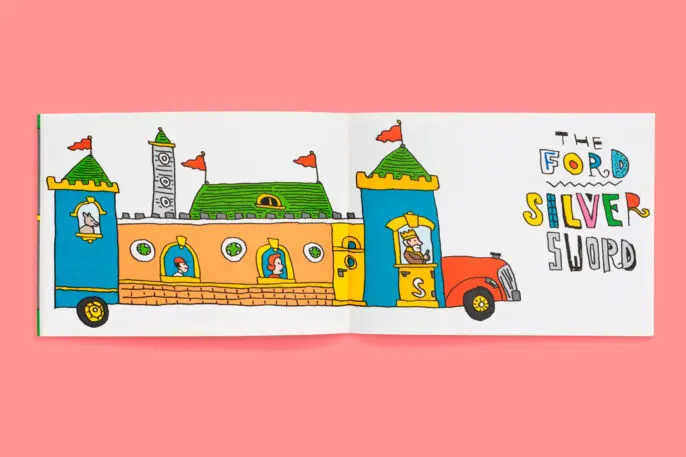

The card tells the story behind the Edsel through Moore’s correspondence with Young (whose letters were actually written by his secretary). With writerly dignity, Moore refuses payment until she’s come up with the perfect name. The car still unseen, she throws out “The Ford Silver Sword,” before realizing some sketches of the car’s appearance might help her in the process. Bierut hasn’t seen those sketches but in one of her letters, Moore describes them as having “toucan tones” and “a sense of fish buoyancy.” In that same letter, Moore puts forward “The Impeccable,” and in subsequent letters: “Bullet Lavolta,” “The Arc-en-ciel” (“The rainbow” in French), “Dearborn Diamante,” and many other poetically named possibilities.

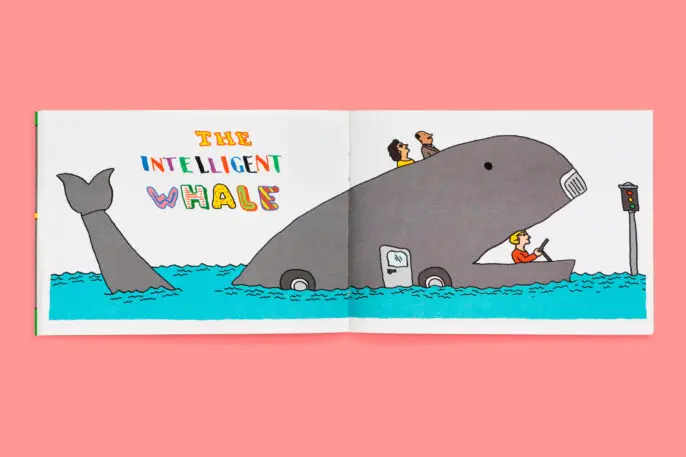

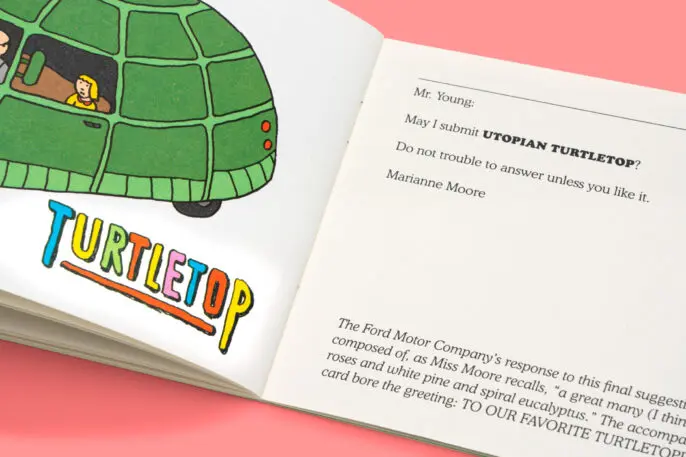

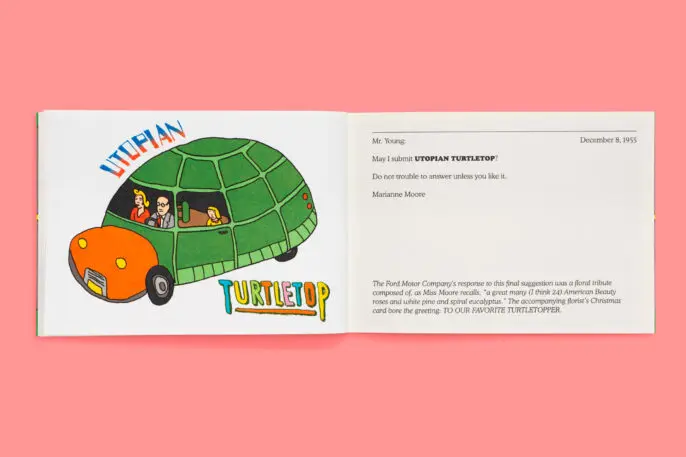

The letters are interspersed with whimsical illustrations from graphic design legend Seymour Chwast, who brings some of Moore’s name suggestions to life with incredible wit. The “Ford Silver Sword” is portrayed as a castle on wheels, with oversized turrets, and what looks like a wolf riding in the back. The “Intelligent Whale” is operated by a woman steering a wheel in the mammal’s mouth, obeying the rules of traffic, as evidenced by a floating traffic light on the surface of the water. “We approved every one of his sketches,” says Bierut. “I remember literally opening that file and laughing out loud.”

To say that Moore’s suggestions were out of the ordinary would be an understatement. Bierut describes them as “delightful and off-the-wall,” but many of them, including her final suggestion, weren’t exactly viable car names. “I’ll often say you can name anything anything, but I’m not sure ‘Utopian Turtletop’ is a name for a car under any circumstances at any time,” says Bierut.

Still, history has proven that there are benefits to hiring someone who can bring an unusual point of view to the branding process. Microsoft hired the musician Brian Eno to compose its Windows 95 startup sound. And David Rockwell teamed up with the choreographer Jerry Mitchell to streamline how people move through the JetBlue terminal at JFK. “What’s interesting with someone like a poet isn’t that you’re bringing in someone who’s unencumbered by rules,” says Bierut. “What’s interesting is they are bringing in an entirely different rule set that’s created by a different way of looking at language.”

Moore’s final submission (and perhaps her most iconic), “Utopian Turtletop,” earned her the nickname from the Ford team of “favorite Turtletopper.” It took nearly a year after this last submission for Young to tells Moore that Ford ended up choosing “Edsel.” (In total, Ford sourced more than 6,000 names from various candidates.) “It has a certain ring to it […] At least that’s what we keep saying,” Young wrote to Moore.

That the company sifted through 6,000 names suggests the amount of pressure Ford was under at the time. “This was going to be their big car of the year, or the decade, and lead them into the ’60s,” says Bierut. “The more pressure there is, the more people start to transfer that pressure onto the magical name.”

The Edsel launched during the recession of 1958 and was available for only two years before it was pulled from the market. Can we blame the name? In retrospect, maybe, but more often than not, the influence of a name depends on the product behind the name. “If you were in the room when they said ‘let’s call it Google’ you might’ve just thrown up,” says Bierut. “What makes Google isn’t that it’s inherently a good name. Its success makes the name seem successful.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.