Strikes, walkouts, union wins, and even more workers organizing—the wave of labor action that gained momentum during the pandemic showed no signs of slowing down in 2022. In fact, it ramped up even more: The number of union election petitions filed with the National Labor Relations Board increased by more than 50% in 2022.

“That data point alone tells us that there’s rising worker activism, there’s rising worker organizing, and there has been rising worker success,” says Seth Harris, a professor at Northeastern University who was also a top labor advisor to President Joe Biden and an acting labor secretary under President Barack Obama.

Among the most prominent wins in union efforts this year came from workers at two major companies: Starbucks and Amazon. Starbucks workers alone won more than 260 union elections since a Buffalo store became the first to unionize in December 2021. In April 2022, Staten Island Amazon warehouse workers won their union election, a historic first for the company.

But while Amazon and Starbucks may have dominated labor headlines this year, they weren’t the only places that workers were organizing. In 2022, North America’s Building Trades Unions signed a project labor agreement with offshore wind developer Ørsted, a first of its kind for the U.S., which ensures construction of offshore wind farms will be done with American union workers. The United Auto Workers just won a union election at a General Motors battery plant, a key to ensuring that as the car market shifts to electric vehicles, union workers will have roles in their production.

More industries saw union efforts in 2022, as well, from video games and animation to Apple stores and museums and libraries. The first Trader Joe’s to unionize did so in in Massachusetts in July 2022 (a second followed in August). After United Farm Workers marched in August, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed a bill making it easier for agricultural workers to join unions.

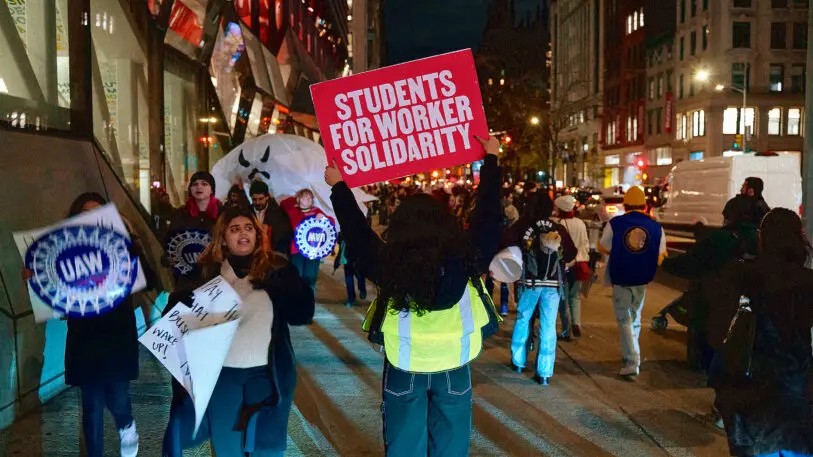

Workers across the country also went on strike: The biggest strike this year was made up of 48,000 academic workers at the University of California, the largest such strike in U.S. history. Adjunct professors at the New School recently ended the longest adjunct professor strike in U.S. history; the 1,800 workers reached a tentative agreement that will boost their wages, protect health care benefits, and add paid family leave.

But not all workers who wanted to strike were able to. Thanks to the Railway Labor Act (a different labor law from the National Labor Relations Act), railways and airlines are deemed “critical infrastructure,” and thus Congress can intervene in labor disputes. Congress and Biden did just that when they blocked a national rail strike in December. These workers haven’t given up though, and are continuing to pressure Congress and Biden to address their working conditions, most prominently their request for paid sick days.

So what’s next for 2023? Though the averted rail strike stoked some worker frustrations against the Biden administration, Seth Harris says labor as a whole is still supportive of Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris, and that the administration will have a big role in the movement’s future. “That doesn’t mean the labor movement gets everything it wants, but means that it gets heard,” Harris says, “and they know that they’re uppermost in the president’s mind.”

After high-profile wins at places like Amazon, Starbucks, and Trader Joe’s, the question now is whether those unions can secure their first contracts in 2023. There’s no guarantee it’ll happen, as negotiations can often drag out; Philadelphia Museum of Art workers ratified their first contract in 2022, two years after unionizing.

And with the way many employers have fought back against union efforts, those negotiations could be big fights. Trader Joe’s, for example, was accused by the union of breaking the law when it fired an activist. Meanwhile, Starbucks violated labor laws in refusing to negotiate, and also withheld pay and benefits from unionized stores. The coffee chain has closed stores that have unionized; though the company says it did so for business and safety reasons, the union claims it did so in retaliation.

There’s also more important negotiations coming up. The United Auto Workers will begin contract negotiations with the “big three” automakers: Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler (now Stellantis), which will be especially important as electric vehicles become a more significant part of the auto industry. Maritime port workers on the West Coast still don’t have a resolution to their contract negotiations, which began in May 2022, and which could ultimately affect supply chains. The Teamsters also have a new leader in Sean O’Brien, who ran for the position on a promise to get United Parcel Service workers a better deal with a new contract (he also wants the Teamsters to be involved with organizing Amazon warehouses).

But even as many workers struggle to unionize and have their contracts finalized, there’s increasing public support for their organizing: 2022 saw the highest public support for labor unions since 1965, with 71% of Americans now approving of labor unions. That’s unlikely to falter. “I don’t see any reason for the public to turn away from the labor movement,” Harris says. “Quite to the contrary, I think working people in this country understand the value of unions. . . . They see the labor movement advocating for protections for workers from the pandemic; advocating for workers to get an additional pay because they had to work as essential workers; lobbying for public goods like infrastructure, like funding for COVID relief, like funding for climate resilience. I think they see the labor movement now not merely as a special interest but as part of a public interest.”

But while support for the labor movement may continue, that’s not all it needs to be successful. “The question is, can the labor movement turn that support into more members, into more organizing, into more contracts?” Harris says. “2023 is going to help us understand the answer to that.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.