In typical commercial kitchens, chefs plan detailed menus way ahead of time, and their food deliveries fulfill those specific menus’ needs. But one Pittsburgh-area kitchen is flipping that system, instead designing its menu based on the mishmash of food it gets—be it sauerkraut, cantaloupe, or ketchup.

This isn’t an episode of Chopped, but business as usual at the Good Food Project, a food recovery kitchen in Millvale, Pennsylvania that receives donated excess food that would otherwise end up in the trash and turns it into daily meals for the food insecure. And it creates zero waste—or 0.023% waste, as measured by tracking tools—a figure almost unheard of, when “zero waste” tends to mean closer to 10%. To achieve that, the kitchen plans meals only once it receives the food, which may vary wildly week to week, rather than trying to fit food around planned menus. Though unpredictable and challenging, it’s worked so far and proven to be a model that could expand to other cities.

The kitchen started operations in 2019, as part of 412 Food Rescue, a Pittsburgh-based food recovery organization, to test whether their food waste could actually fall to zero. Food waste heavily contributes to climate change because of the the methane it produces in landfills. As such, exaggerated claims of zero waste seem akin to greenwashing, says Leah Lizarondo, the CEO and co-founder of 412 Food Rescue. What’s more, 40% of food around the world is thrown away, even though more than 800 million people don’t have enough to eat.

As part of its day-to-day work, 412 Food Rescue redirects wasted food from various sources. It would often try to give leftovers to kitchens that serve the food insecure, but realized most were stringent in terms of what they would accept. It was hard to find kitchens that would take “strange configurations of unplanned ingredients,” Lizarondo says. The Good Food Project was a way to show the possibility of improvising menus with constantly changing ingredients.

That required a chef who’d be amenable to that unpredictable workflow. The responsibility came to Greg Austin, who had more than 10 years of experience at local restaurants. Every week, he receives about 2,500 pounds of food in two deliveries from foodservice partners; some weeks, he may get surplus protein, in other weeks, excess produce—food that was produced to meet an anticipated demand, but was never served. Once, for example, he received the equivalent of half a cow from a meatpacker and he had to get creative in drawing up six to eight beef dishes for the week ahead.

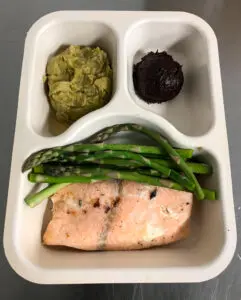

The kitchen started a pilot phase in 2019, testing menu processes and experimenting with smaller quantities. During the pandemic, it produced about 300 meals a week. This is the first it has has been fully operational. They’ve installed walk-in fridges and freezers with capacity to store items that can’t be used on the fly—for instance, in the event that 40 commercial-size tubs of sour cream land at the facility. With the help of another chef and a few volunteers, Austin makes about 1,200 meals a week to be frozen and reheated by the recipients, including a new main dish, side dish, and dessert each day.

It has produced some fun challenges—like the half-cow conundrum. Fresh fruit can be hard to work with, especially melons that don’t work in desserts like pies. When partners delivered heaps of cantaloupes, Austin had to get creative: He started juicing and fermenting the melons, adding honey and yeast to make cantaloupe vinegar, which served as a dressing or reduction. In another case, a local college with an on-campus trout farm donated 100 trout. They eventually decided on trout fritters, a spin on the more familiar cod fritters.

Now, the kitchen works almost exclusively with Gordon Food Service, a broadline distributor, which makes logistics easier, though deliveries are still unpredictable. Like the trout fritters or the cantaloupe dressing, the goal is to design familiar meals, but tweak them based on what they receive. “Even if it’s something off the wall, we try and reel it back into something that’s understandable and accessible and likable,” Austin says.

Volunteers deliver the frozen meals to one of 412’s partner nonprofits nearby, including Allegheny YMCA, Second Harvest, and Housing Authority of the City of Pittsburgh, which then distribute them to food-insecure people.

According to Austin, 81% of the food received goes into the meals; a further 9% to other 412 Food Rescue operations, and the remaining almost 10%—largely vegetable scraps—is composted. Using surplus food also translates to almost zero cost; Lizarondo estimates the cost at about 8 cents per meal. Austin says they haven’t bought any food themselves since May 2020. They use the dry pantry items like oats, pasta, and rice sparingly, “trying not to let our enthusiasm burn through that as fast as the fresh stuff.” (Most of the kitchen’s operational costs goes to rent; the initial equipment installation totaled about $150,000).

They’re able to glean the waste figures thanks to tracking tools from Leanpath, a company that helps foodservice organizations, such as Sodexo, Aramark, and Google, reduce waste. “We discovered that food waste is really the elephant in the kitchen,” says Steve Finn, Leanpath’s vice president of sustainability. “It’s excessive, but it’s unaddressed.” Better measurement makes the problem visible, in order to create a culture of change, and ways to address inefficiencies.

The Good Food Project has aimed for 0.05% waste, but has surpassed that goal and is currently just producing 0.023% waste (out of about 166,200 pounds of food, only 39 ended up in the trash). According to Finn, that’s “exceptional,” and one of the lowest he’s ever seen. “Zero waste . . . typically doesn’t mean zero, and they’re about as close to zero as anyone can get.”

While most kitchens only focus on their own waste, Good Food also considers its sources, making for somewhat of “a twist on our typical tracking process,” Finn says. If it can’t handle excess of a certain item, or would like more of something, they communicate that to their sources, in turn helping them stop overproducing and become more efficient, too.

Now, Lizarondo wants to expand the model to food rescue kitchens in other cities (412 already operates in more than cities, including Cleveland, Los Angeles, and Vancouver). “Can you imagine these kitchens that produce meals using surplus food, and it costs them zero instead of even $1.50 per meal?” she says. “That’s a lot.”

She wants to show that the model is viable, and that while the spontaneous workflow is daunting, creating meals on the fly is possible. “I don’t want to discount Greg’s talent,” she says. “I think it’s more of changing the way you think, that it’s not such a hard thing.”

Austin agrees, saying it’s about creating a mentality shift, and dropping any egos, which can be hard for restaurant-trained chefs. “The challenge was coming to a paradigm shift where we don’t plan ahead,” he says. “Putting yourself in a position of service, and humbling yourself, will change how difficult that is.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.