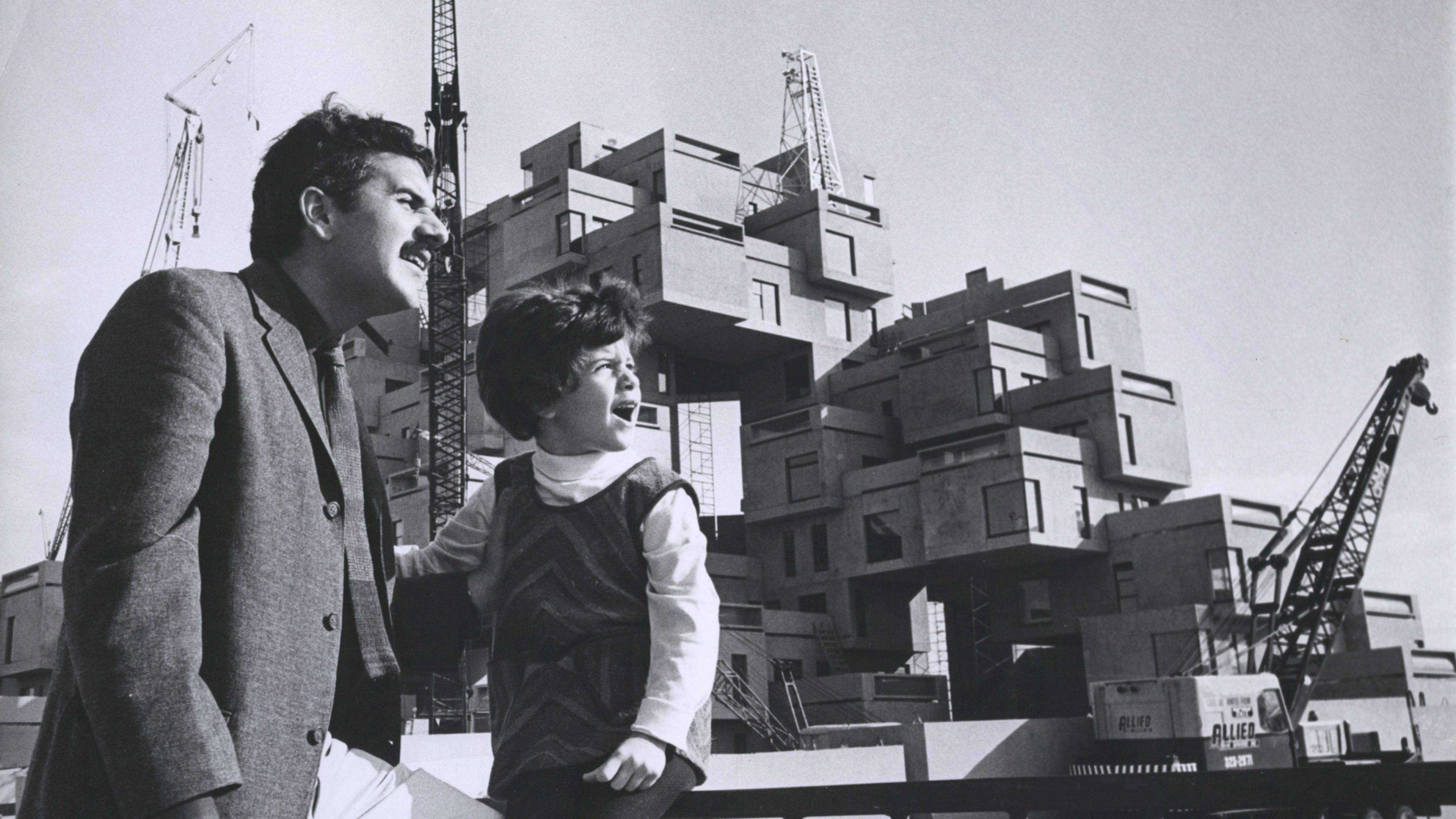

From a university design project that became one of the most recognizable apartment complexes in the world to major urban developments in Asia that span millions of square feet, architect Moshe Safdie has steadily and sometimes perilously pursued the dreams of mega-scale architectural design. His first project, the fractal-like concrete module housing project Habitat 67, remains an influential example of residential design; and his firm Safdie Architects’ blockbuster projects like Singapore’s Marina Bay Sands and Chongqing’s Raffles City have pushed the limits of vertical urbanism. In a new memoir, If Walls Could Speak, Safdie traces the highs and lows of a career that has spanned seven decades.

Safdie is known for such extraordinary work as the National Gallery of Canada, Yad Vashem Holocaust History Museum in Jerusalem, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, and the lush garden and fountain spectacle of Singapore’s Jewel Changi Airport. He’s also experienced repeated headwinds and failures on projects attempting to combine architecture and city building into large-scale megastructures. In many ways, these projects are expansions on Safdie’s original plans for Habitat 67, which proposed an entire community encompassed in a mixed-use complex, with skywalks linking internal neighborhoods and each apartment with its own rooftop garden. What got built in Montreal was only a small portion of a broad vision. Now, at age 84, Safdie is finally seeing some of these early ideas take form.

Born in 1938 in Haifa, Palestine (now Israel), Safdie and his family were present for the founding of Israel a decade later, and a young Safdie had idealistic visions of joining with his friends after their military service to start a communal farm. When Safdie was 15, his textile-importer father decided to leave what he saw as an oppressive business climate in Israel and move the family to Montreal, an uprooting Safdie calls “deeply traumatic.” A self-described wild child, Safdie became a more serious student in Montreal, finding interest in literature and science. A high school aptitude test made a prophetic career suggestion: “It said ‘suitable for architecture,'” Safdie recalls. “That was enough.”

Safdie enrolled in Montreal’s McGill University, in a six-year architecture program. Before his final year of studies, he was awarded a traveling scholarship that took him on a U.S.-Canada tour of major housing developments, including public-housing projects like Cabrini-Green in Chicago and suburban tract homes in Levittown, New Jersey. It was a formative experience that directly led to his thesis project exploring a site-agnostic system for building community-focused housing. That concept eventually became Habitat 67, the fractalized apartment complex built for Montreal’s 1967 International and Universal Exposition, and has gone on to inspire Safdie’s projects—built and unbuilt—ever since.

Moshe Safdie: The original Habitat, the one that didn’t get built because the government decided we were only going to do a little piece, was really a whole community. It had offices in it, it had a school, it really was a sector of the city. And on top of it was the ambition of rethinking construction systems. They were two challenges running parallel to each other, and one nothing to do with the other. A tough thing to do. And it is unfortunate because people relate to Habitat as a housing building because it’s small—150 apartments—but the idea was bigger. Some of the later Habitats that didn’t get built tried to cope with that scale. But it’s only now, in the last 15 years and mostly in Asia, that we’re actually able, ourselves, to go back to projects with that scale and that mix and work at the scale of the city instead of just the individual building.

FC: Those Habitats that didn’t get built—a pyramid-like version for New York, a proposal in Washington, D.C., and one partially built but never completed version in Puerto Rico—they highlight the challenge of this kind of large-scale planning and designing. There’s so much potential for things to fall apart. How have you had the perseverance to keep pursuing these kinds of projects even though for various reasons they often don’t get realized?

MS: I think it’s a combination of conviction and a character that is persistent. I just don’t give up. Mamilla in Jerusalem took me more than 35 years to realize. It wouldn’t be there if I didn’t persist. I was the only one there, alone at some points, pushing for it. I think you’ve got to be passionate and have a strong conviction, but you have to have a character that doesn’t get tired.

MS: Yes. There were many such moments. In fact, one moment involved a friendship. My dear friend, an architect, gets appointed chief planner of Jerusalem, with my help. And he turns on me, in the sense of not supporting the project and trying to introduce major changes, some of which would compromise it. At some point you say this is too much. But in the end, the impact on the city was to me so significant that I could not give up. I knew it would change the nature of the relationship between the old and new city. Mamilla created such a vital bridge that you can’t even think of them as separated.

FC: I was surprised to read in the book that you even at one point considered running for mayor of Jerusalem.

MS: I did. Teddy Kollek [Jerusalem mayor from 1965 to 1993], who I was very, very close to, was stepping down, and the people running for office were all just politicians, [eventual Israeli Prime Minister Ehud] Olmert and people who were not committed to the city, who had other agendas. And I, somehow naively, or maybe not so naively, I thought if I could become mayor, I could bridge a bit the Palestinian divide, get the Palestinians to vote because I could speak a little Arabic and appeal to that sector. And I also thought I could make a difference to the planning of the city in a big way. But as my wife pointed out that is a big decision because it means giving up architecture. At the end I felt I have more to contribute as an architect going forward than the chance politically that I’d be successful, which has a high probability of failure anyhow.

FC: You write about going to meet with Robert Moses, the notorious New York official who epitomized the fraught nature of top-down urban transformation. A lot that can be said about Robert Moses and his impact on cities, but there’s also an argument to be made that when someone has a broad vision, they can try to address issues in a big way. Do you still think there’s the potential for that approach to work?

MS: Absolutely. Let’s start with Moses. Just because he had poor judgment about some of what he did doesn’t negate what he achieved and the scale at which he operated. I think Moses has to be thought of in the same frame as the City Beautiful movement, the Olmsteds of the world, the people who created Central Park and the emerald necklace in Boston. These were civic leaders who really believed in that scale of intervention. It’s that tradition that Moses is a part of. He erred in his judgment, and it’s hard to fault him because the whole modern movement erred in its judgment. Le Corbusier was talking about ripping out the streets everywhere [and replacing them with mega “motor-roads”] and we complain about Moses that he wanted to pass a freeway that would have affected neighborhoods. But it’s the avant-garde architects who are preaching the end of the street. The impact of Jane Jacobs [and giving voice to community members] is a positive contribution. But now the pendulum has gone too far. The infrastructure bill that was just passed, there’s no chance we’re going to see dramatic results unless we change our ways in terms of plan approval, scale of consideration, scale of intervention, overriding some obstacles even if a particular interest group opposes it. You can’t give a veto power to everyone if you do things at that scale.

FC: You have managed to do some work at that scale, in China, for example, and in several major projects in Singapore.

MS: They don’t ask. In Singapore it’s easier because the voice of the community or any small opposing voice can be quashed.

MS: It is. You’re working in a political system where there’s much more concentrated authority. It’s able to think big and implement big. That’s true of China, and that’s true of Singapore without all of the oppression—they have elections, they have courts. But still, the very fact that most of the land is publicly owned in Singapore gives the government enormous control. This makes it possible to do things in Singapore that you wouldn’t even consider here. It also has results. Because unlike when you have a major urban project in a city like New York, it’s not just each developer doing his thing because they set goals for each district which they impose on every developer in order to make it work cohesively. We don’t have any of that. Planning has been really discredited and almost eliminated in most American cities.

FC: One of your most notable projects, Marina Bay Sands, has become iconic for its soaring skypark and pool stretching horizontally across 3 towers, 57 stories above ground—which people probably know from the film Crazy Rich Asians. In the book you write that you came up with that signature element by saying “Well, why not?” So that came about almost as a whim?

MS: It did. We were standing there, and we had three towers and we had the podium. And the pressure was to try and put all swimming pools and parks on top of the podium, which is what they always do in Vegas. And it seemed so improbable to me. These were enormous spans, they would be in the shadow of the towers for six hours a day. It just didn’t seem to make any sense. And it was like a spontaneous thing. Why not? And everything followed. You don’t get many real eureka moments, but that’s one of them.

FC: Habitat seems to loom over your work. You mention in the book this yearning to achieve that type of concept at a much higher density and larger scale than you did in Montreal, or even in Singapore and elsewhere. Do you see that on the horizon? Can that happen for you, for your firm moving on?

MS: I see it for my firm, but beyond that. The ideas of Habitat were partially ignored, partially ridiculed as a one-time thing, for at least 20 years. But now it’s changed completely. Because the next generation, if you think of the various offices, such as the offshoots of OMA, Bjarke Ingels Group, Herzog & de Meuron, they’re all embracing these ideas. There’s Habitats cropping up everywhere. They’re becoming part of the mainstream of the avant-garde, and that’s what makes me both happy and optimistic. It’s gone beyond me.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.