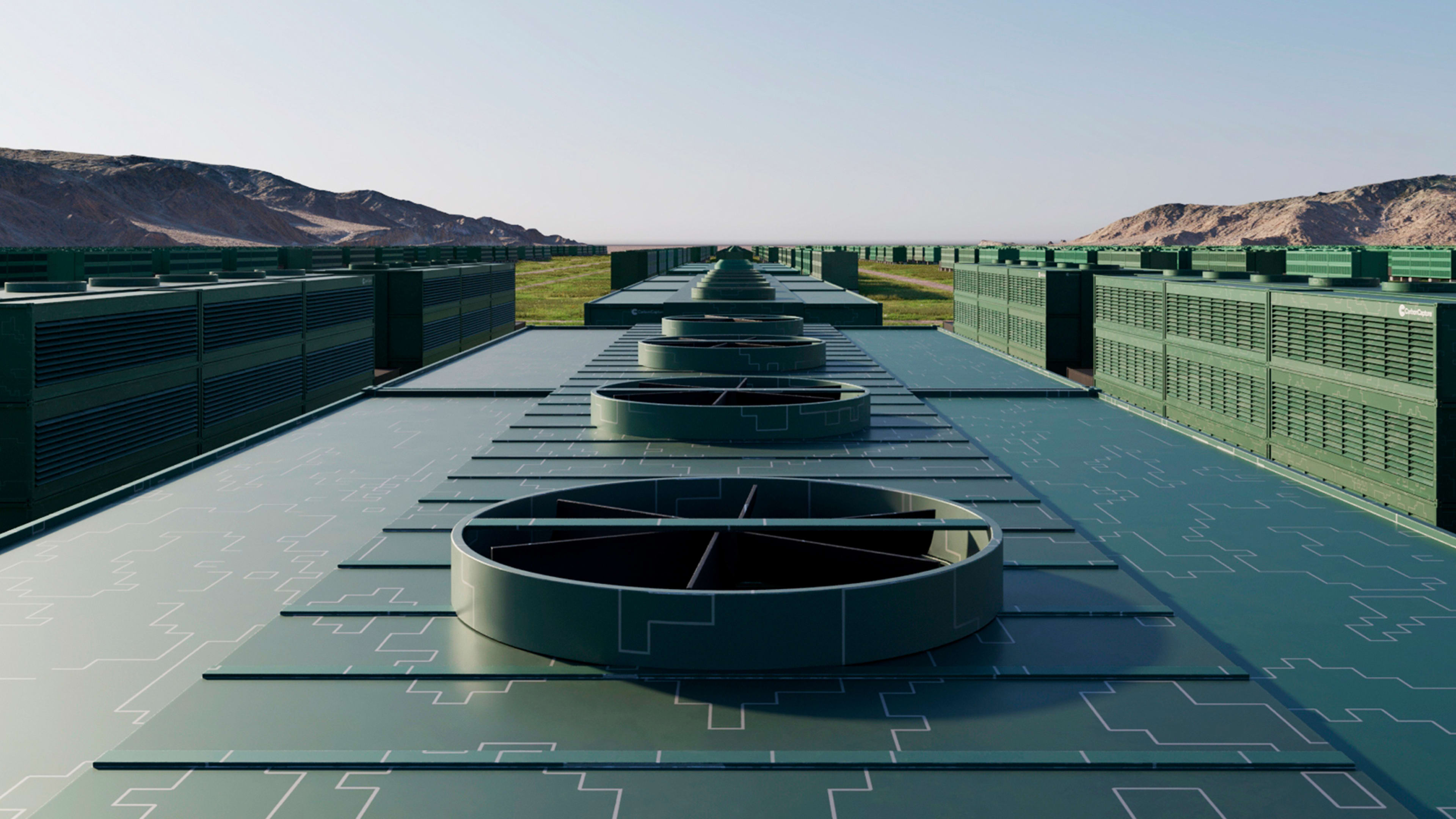

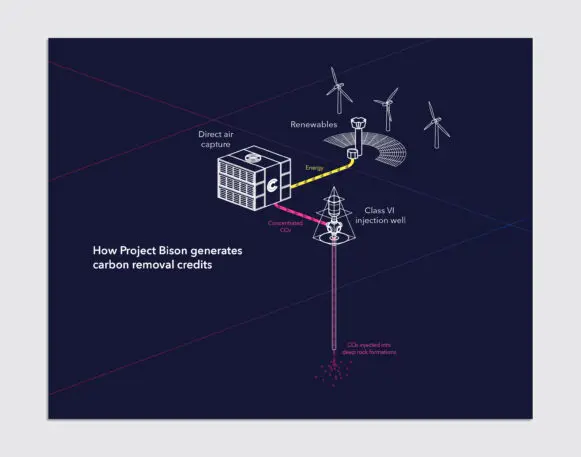

In rural Wyoming, a sprawling field will soon be filled with dozens of shipping container-sized boxes that can pull CO2 from the atmosphere to help combat climate change. The captured CO2, compressed into a liquid, will travel through pipelines into nearby wells that are drilled thousands of feet underground, storing it permanently. Everything will run on clean energy.

It’s still a very expensive way to clean up carbon pollution: a single ton of captured CO2 costs hundreds of dollars. CarbonCapture’s initial prices will start at $600-$700 to buy a credit for one ton of carbon captured and permanently stored. (To put that in perspective, humans emitted more than 36 billion metric tons of CO2 from energy use in 2021; between 1850 and 2019, we emitted more than 2.4 trillion tons. Some of that went into the ocean and land, and the rest went into the atmosphere, where it’s now wreaking havoc on the climate.)

CarbonCapture is working to reduce cost in part by finding cheaper materials to absorb CO2 inside its machinery. Because dozens of new sorbents are now being developed specifically for direct air capture, the company’s technology is designed to work with them interchangeably, so the equipment can easily be updated as the field progresses. The material it might use in 2030 may not yet exist. “It’s highly likely that there’s going to be a significant number of advancements,” Corless says. “So the best materials just still literally haven’t been invented yet.” By the end of the decade, it expects its price to drop to $250 per ton of captured carbon.

It also helped that there has been a surge in interest from companies that want to offset their own emissions, but that are wary of some of the issues with traditional carbon offsets and want to be sure they’re paying for services that can permanently sequester CO2. Frontier, a group organized by leaders in the space including Stripe and Alphabet, has committed to buy nearly $1 billion in carbon removal services from nascent startups to help them grow. “It was that movement, even before the IRA passed, that gave us the foundation of a business,” says Corless.

Other projects are also moving ahead. Carbon Engineering, another startup, and 1PointFive, an oil company subsidiary, are building a facility in Texas that will capture one million tons of CO2 a year. 1PointFive has laid out a vision of building 70 direct air capture plants by 2035. Climeworks, the company with the first facility in Iceland, is assessing the feasibility of building plants in the U.S. that could capture 100,000 tons of CO2 a year.

Rather than building multiple smaller plants, CarbonCapture wanted to focus on a project that could quickly scale up in place. Wyoming was an ideal location, partly because the geology is well suited to store captured CO2 underground. (Frontier, its carbon storage partner, said that it couldn’t disclose the specific location of the site in Wyoming because it doesn’t want to tip off competitors.) Wyoming’s regulations make it easier to get permits to store CO2 underground. It can also help the state transition from fossil fuels: Well-paid jobs building and operating direct air capture plants can help replace jobs from dying industries like coal.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.