Designer Issey Miyake has died at age 84, leaving an indelible mark on the fashion world. He was celebrated for clothing that responded to the body in movement and which was conceptual in design but also completely appropriate for the everyday. His garments were often based on simple geometric shapes made in finely pleated fabrics that resulted in new and unexpected silhouettes.

Miyake stood out from the fashion crowd in several ways. For a global audience, it was poignant and meaningful to see a nonwestern designer not only establish their own successful multicultural fashion business internationally but also propose fashion beyond the established and conventional silhouette, fabric styles, and imagery.

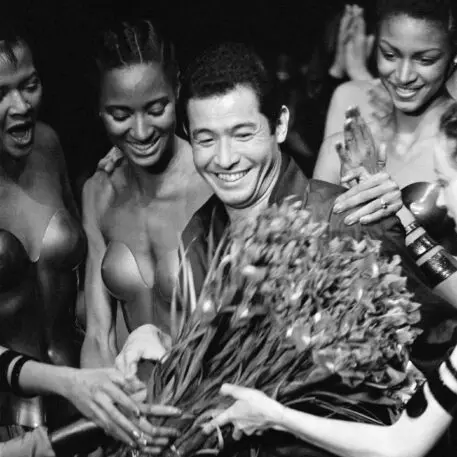

There’s much for the next generation of fashion designers to learn from Miyake’s body of work, from his innovative reinvention of Japanese clothing traditions to his bravery in embracing new textile technologies and silhouettes. Perhaps most relevant for the modern audience was his inclusive vision, his aim of “designing for the many.” He demonstrated this not just through the design and cut of his garments, but also in the models he chose to include in his shows and campaigns. Miyake always ensured that “the many” meant including models from underrepresented backgrounds.

An egalitarian vision

Born in Hiroshima, Japan, in 1938, Miyake was seven years old when his hometown was destroyed by the atomic bomb that signaled the end of the Second World War in Asia. He sustained a serious leg injury and lost his mother to radiation sickness soon after, events that inspired him to “think of things that can be created, not destroyed.”

Miyake went on to study graphic design at Tokyo’s Tama Art University before attending the École de la Chambre Syndicale de la Couture in Paris in 1965. He witnessed the revolutionary May 1968 protests in Paris, a series of student and worker demonstrations that resulted in improved workers’ rights and rapid social change. This led Miyake to question the status quo and inspired him to think in a more egalitarian and radical way about fashion design.

Miyake was fascinated by the interaction between clothing and the body, exploring what fashion could be. This is evident in his many innovations, especially in the way he blended his Japanese heritage with his European and North American experiences. He developed his vision for contemporary fashion, combining the comfort of Western styles with the textiles and silhouettes of the East, exploring Japanese gangster tattoos as textile designs, sashiko quilting for coats, and Kimono-inspired geometric shapes for handkerchief dresses.

Breaking with convention

Alongside designers Rei Kawakubo and Yohji Yamamoto, his work was part of a wave of Japanese designers who established the relevance of a fashion perspective from outside of the dominant Euro-American narratives of fashion. When I studied fashion history in the 2000s, it was as if it only existed in London, Paris, Milan, and New York, but this “new wave” of Japanese designers paved the way for other international designers to follow.

Throughout the 1980s, Miyake continued to experiment, showcasing his work in museums and galleries. He explored further with materials, for example: moulded breastplates, bamboo and rattan bodices that began to look like sculptures, all the while always using fashion as a tool to study the body. In 1981, he created Plantation, a pioneering gender-neutral range, designed to be worn by all ages and body shapes in natural easy-to-care fabric. The collection was revived and renamed Issey Miyake Permanente in 1985.

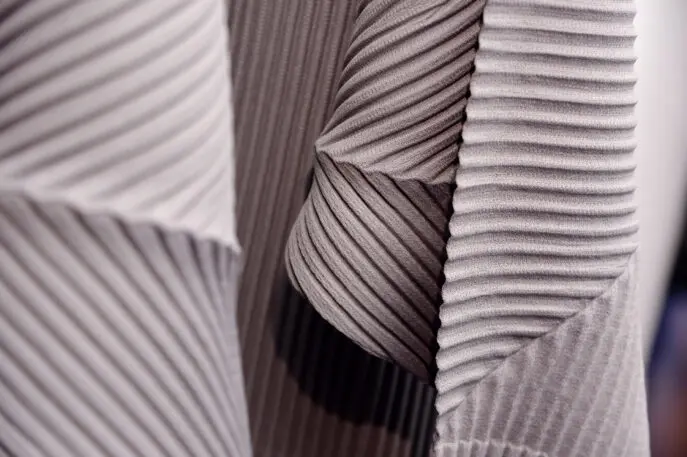

His brand Pleats Please was established in 1988, a range of garments made from a new pleating technology he developed for pleated cloth. The pleats provide a functional benefit as they create stretch within a garment, allowing for versatile sizing. This was another playful development in Miyake’s disruption of boundaries.

Miyake brought this spirit of experimentation and boundary-pushing to his shows as well. This was best exemplified in his radical show, Issey Miyake and Twelve Black Girls, which took place at the Seibu Theatre in Tokyo and the Osaka Municipal Gymnasium. Running for over a month, the show put 12 Black models, including Grace Jones, front and center in a way that had never been done before.

In her autobiography, Jones highlighted the value of Miyake’s support when she was a young model in Paris. This episode is representative of his forward-thinking attitude and inclusive mindset at a time when it was unusual to showcase designs exclusively on models of color.

Whether he was reinventing garment shapes, using technology to pleat innovative fabrics, reducing fabric waste or designing non-gendered pieces, his vision was always modern and for everyday wear. Issey Miyake was a true trailblazer, and his pioneering vision will be sorely missed.

Noorin Khamisani is a lecturer in fashion and textile design at the University of Portsmouth.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.