The pandemic threw up a barrier for the research of Laura Mauldin. A sociology professor at the University of Connecticut who studies disability and caregiving, she’d planned to visit the homes of people with disabilities to see the ways they set up their space for their particular needs. The pandemic put a halt to those visits. Though Mauldin could still peek into homes via video calls, many of the small details she could see in a real-life visit fell out of view in the virtual space. So, she started asking people to send photos.

What she got was a flood of innovative hacks, modifications, and do-it-yourself problem solving, all aimed at making homes work better for people with disabilities and those caring for them. “I thought, ‘This is brilliant,’ but it’s under the radar, it’s hidden in the intimacies of our homes, no one else sees this,” Mauldin says. “And I thought, ‘We have to show it to other people.'”

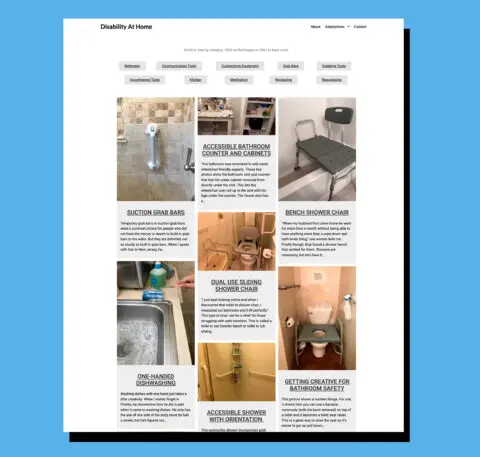

[Screen Capture: disabilityathome.org]So Mauldin began compiling these photos and created Disability at Home, a website documenting the varied, inventive, and often banal ways people have augmented their homes to improve life with a disability. One modified and elongated the steps leading to their front door with plywood and two-by-fours. Another attached a rolling dolly to his wheelchair so he could more easily move around the house with objects. Others have used common things like zip ties, painter’s tape, and dry erase boards to hack their homes and ease their daily routines.

“When I speak with people during the course of my research, so many of them talk about how frustrating and stressful it is to deal with what we might think of as really basic day-to-day things that need to get done,” says Mauldin, who is working on a book about caregiving and living with disability. “When houses aren’t designed in an accessible way, or when objects aren’t designed in an accessible way, that creates some problems, and people have to get creative.”

Disability at Home shows the wide variety of ways disabled people and caregivers have solved that problem for themselves, including DIY grab bars made out of gas pipes and a combination commode and shower chair made out of PVC tubing. Mauldin says many of these hacks and modifications solve specific problems in a way a formal product probably couldn’t. “It’s nothing that some high-tech corporation can come in and have this fantastic object to solve,” she says. “That’s not how it works because everyone’s needs are different, and everyone’s trying to craft their space in ways that work for them.”

But that doesn’t mean companies haven’t tried to market solutions. Liz Jackson is a founding member of the Disabled List, an advocacy group looking at the intersection of disability and design. She’s known for coining the term disability dongle, which refers to the types of products and designs created to help disabled people without understanding what those people actually want or need. These products often get glowing coverage in design-focused publications (including, she notes, Fast Company), even if their utility is questionable. “Then you go over to Twitter and what you find in the comments are disabled people saying we don’t want this. We don’t want innovation. We want infrastructure,” Jackson says. “The way that disability is often written about is it’s not actually about the solution, it’s about the promise. So what happens when you start to ask what is the solution without any techno-utopian promise? And that’s where Laura’s work comes in.”

Jackson, who is a disabled person, says Disability at Home offers a more realistic counterpoint to flashy conceptual designs, and is a site she already has found useful. She recently had surgery on her heart and first saw Mauldin’s website after getting home from the hospital. The hacked solutions felt especially relevant. “I’ve got gooping incisions on my chest and other places, and I’m trying to figure out how to place the bandage so that it doesn’t peel away, or so that I’m not going to hurt the incision,” Jackson says. “Imagery from Laura’s website does more accurately reflect my current experience with disability in a way that I never see reflected in these innovation stories.”

Jackson says Disability at Home shifts the focus from the capital D designers working on these issues to the disabled people and caregivers who are developing their own solutions. “I want disabled people to recognize the agency they have over the products in their life rather than being expected to wait for some innovation to swoop in and save them,” Jackson says. “If we’re careful about how the website is used as a teaching tool, I think it could be very, very valuable.”

There’s plenty of people out there who may be able to benefit from the approaches featured on Disability at Home. Mauldin says there are more than 53 million unpaid family caregivers in the U.S., and many are probably already making their own hacks and modifications. Highlighting their efforts, she says, can help embolden others to find solutions that work for them.

“The way the world is, is the way we’ve made it, and we can make it differently,” Mauldin says. “We can unmake things and remake things. And part of how we do that is by talking about it.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.