Branded is a weekly column devoted to the intersection of marketing, business, design, and culture.

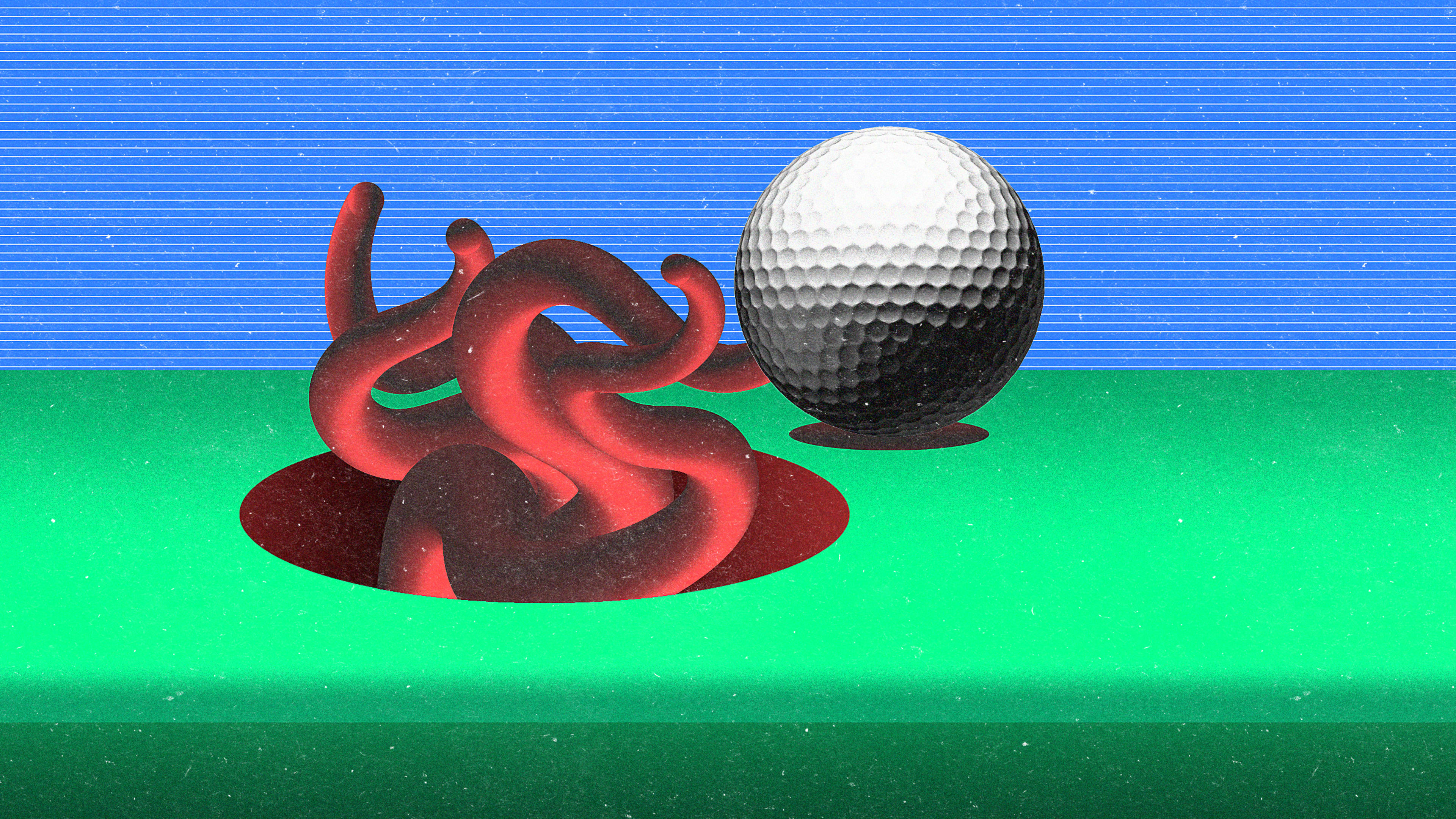

LIV Golf wants to be a game changer.

The new tour, backed by the government of Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund, has been making a lot of noise lately, trying to establish itself as a rival to the famous PGA Tour, and a familiar brand to golf fans and the public at large. And that’s happening —but not quite in the way LIV Golf organizers had in mind.

For starters, pretty much all press coverage of the upstart tour and its attempt to challenge the PGA has cited Saudi Arabia’s troubling human rights record and links to 9/11, as well as the assassination of U.S.-based journalist and dissident Jamal Khashoggi in 2018.

This, of course, is just the sort of subject that LIV was dreamed up to avoid; it was meant to emphasize Saudi Arabia as a sponsor of world-class athletes and a home of innovation, not as a sometimes-brutal regime. In other words, it’s an example of what some have dubbed “sportswashing,” a trendy term for controversial governments using involvement in sports and tournaments to burnish their national brands on the international stage. Think Russia or China hosting lavish Olympic Games, or Qatar’s upcoming role as the setting for the World Cup.

But LIV is, so far, offering a running example of how sportswashing is not only questionable, but also it may not even work. Indeed, LIV’s actual launch is so far having the opposite of the presumably intended effect. The tour has eight events in its first year, four in the United States. (Two of which are at Trump properties.) The first U.S. event got underway this week at Pumpkin Ridge Golf Club, about 20 miles northwest of Portland, Oregon. Local politicians and officials, including Senator Ron Wyden, have openly objected to the proceedings, once again forcing LIV players to defend their involvement with the enterprise. The group 9/11 Justice, made up of individuals who lost loved ones in the terrorist attacks, has also called out LIV golfers for accepting “blood money.”

It turns out that in addition to more familiar critiques and criticisms, in Oregon there’s also a local outrage angle on dubious Saudi government behavior. In 2016, a 15-year-old student named Fallon Smart was killed in a hit-and-run accident. The accused driver was a Saudi student named Abdulrahman Sameer Noorah, who “was facing a trial on first-degree murder charges when he removed a tracking device and vanished,” according to The Associated Press: “U.S. authorities believe the Saudi government helped arrange for a fake passport and provided a private jet for travel back to Saudi Arabia.” In 2020, 60 Minutes did a segment featuring the case, but the topic is resurfacing now because of LIV—the whole ostensible point of which, remember, is to partly soften the Saudi image.

Instead, we now have Wyden declaring: “It’s wrong to be silent when Saudi Arabia tries to cleanse blood-stained hands.” Not exactly the brand message LIV’s backers likely had in mind.

The term “sportswashing” dates to 2015, when critics argued Azerbaijan hosted the European Games partly to divert attention from its controversial human rights record. In a recent interview for the Freakonomics radio show, College of the Holy Cross economics professor Victor Matheson traced the broader idea of government exploiting sports back to ancient Rome, where the ruling class famously relied on “bread and circuses”—including chariot races and gladiator contests—to keep the populace distracted from societal shortcomings.

But in the context of modern geopolitics, there’s actually not much evidence that this strategy works. “I don’t know who’s looking at China any differently now than they did six months ago, and there’s been an Olympics in between,” sports commentator and television host Bomani Jones told Freakonomics. “I don’t think there’s a single person in the United States who, between the 2008 Olympics and the 2022 Olympics, has changed their opinion of China based on what they’ve seen on television [Olympics coverage].”

And while much of the world really doesn’t know much about Qatar right now, we’re all going to hear quite a bit in the months ahead. Its treatment of migrant workers is one likely topic—The Guardian has reported that more than 6,500 have died there just since the hosting decision was made. “Human Rights Watch asserts that thousands upon thousands of migrant workers experienced grave labor abuses while helping Qatar prepare for the World Cup,” The Nation adds. LGBTQ rights are another potential topic: A same-sex relationship can put you in prison for years in Qatar. Plus, women’s rights are severely restricted. That’s not the kind of attention Qatar presumably wants, but it seems inevitable.

The best—and most deeply cynical—case for sportswashing as a tactic is that it invariably sets off a chain of what-aboutism debates on ethical transgression. LIV is backed largely by Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund; so what about that fund’s extensive investments in familiar startups and businesses, from Uber to Boeing? A fair question. Nevertheless, the very debate does nothing but underscore grim Saudi policies and behavior.

In fact, that debate not only undermines the brand it was supposed to enhance, but also sets off a kind of reputational contagion. The LIV is offering marquee players massive, eye-popping paydays, and some have accepted; it probably doesn’t hurt LIV’s case that a lot of players have problems with the PGA. But despite this, the majority of the best-known pro golfers have so far declined the opportunity. Why? Partly because they’re thinking about the longer run—and they’re protecting their own brands.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.