The planet changes quickly: More than half a million acres are burning in New Mexico. A megadrought is shrinking Lake Mead. The Alps are turning from white to green. Development continues to expand, from cities to massive solar farms. All of these changes impact the Earth’s climate and biodiversity. But in the past, such changes have been difficult to track in detail as they’re happening.

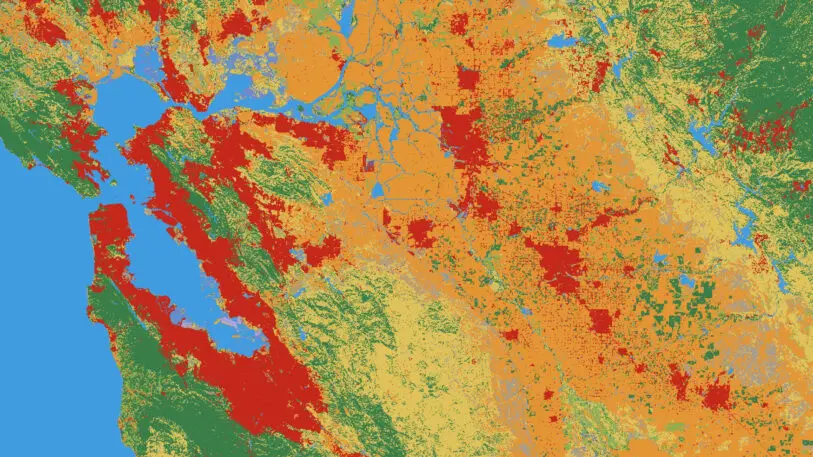

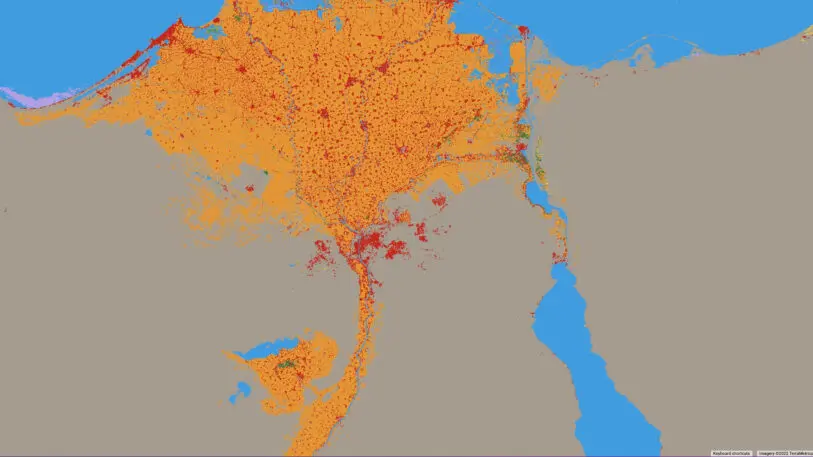

Okavango Delta [Images: Google]A new tool from Google Earth Engine and the nonprofit World Resources Institute pulls from satellite data to build detailed maps in near real time. Called Dynamic World, it zooms in on the planet in 10-by-10-meter squares from satellite images collected every two to five days. The program uses artificial intelligence to classify each pixel based on nine categories that range from bare ground to trees, crops, and buildings.

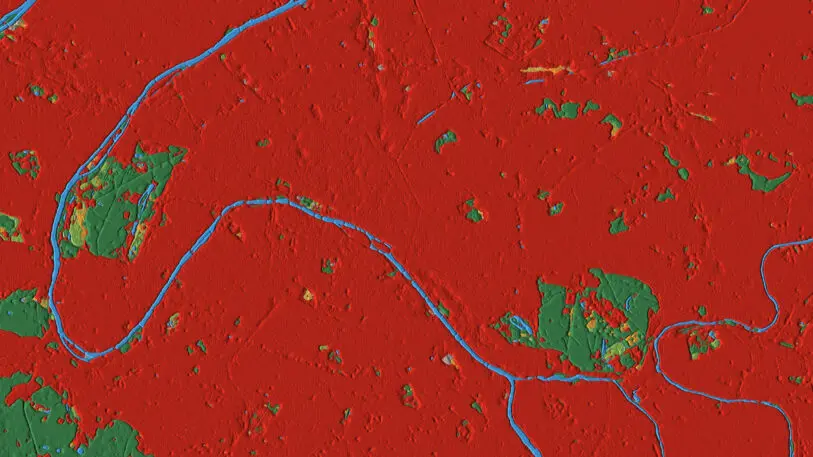

Researchers, nonprofits, and other users can “explore and track and monitor changes in these terrestrial ecosystems over time,” says Tanya Birch, senior program manager for Google Earth Outreach. As the tool was being built last year, Birch used it in the days after the Caldor Fire, a wildfire that burned more than 200,000 acres in California. The pixels in satellite images quickly changed from being classified as “trees” to “shrub and scrub.”

Caldor Fire [Image: Google]Scientists used to rely on statistical tables that were sometimes released only every five years, says Fred Stolle, deputy director of the World Resources Institute’s Forests Program. “That’s clearly not good enough anymore,” he says. “We’re changing so fast, and the impact is so fast, that satellites are now the way to go.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.