No one wants to imagine how they might die, but statistically, we already have a good idea. Sudden cardiac arrest is the leading cause of natural death in the U.S., and when it happens outside a hospital, nearly 90% of people don’t survive. Products called AEDs—automated defibrillators—can help in the first few minutes. But where can you find one in an emergency?

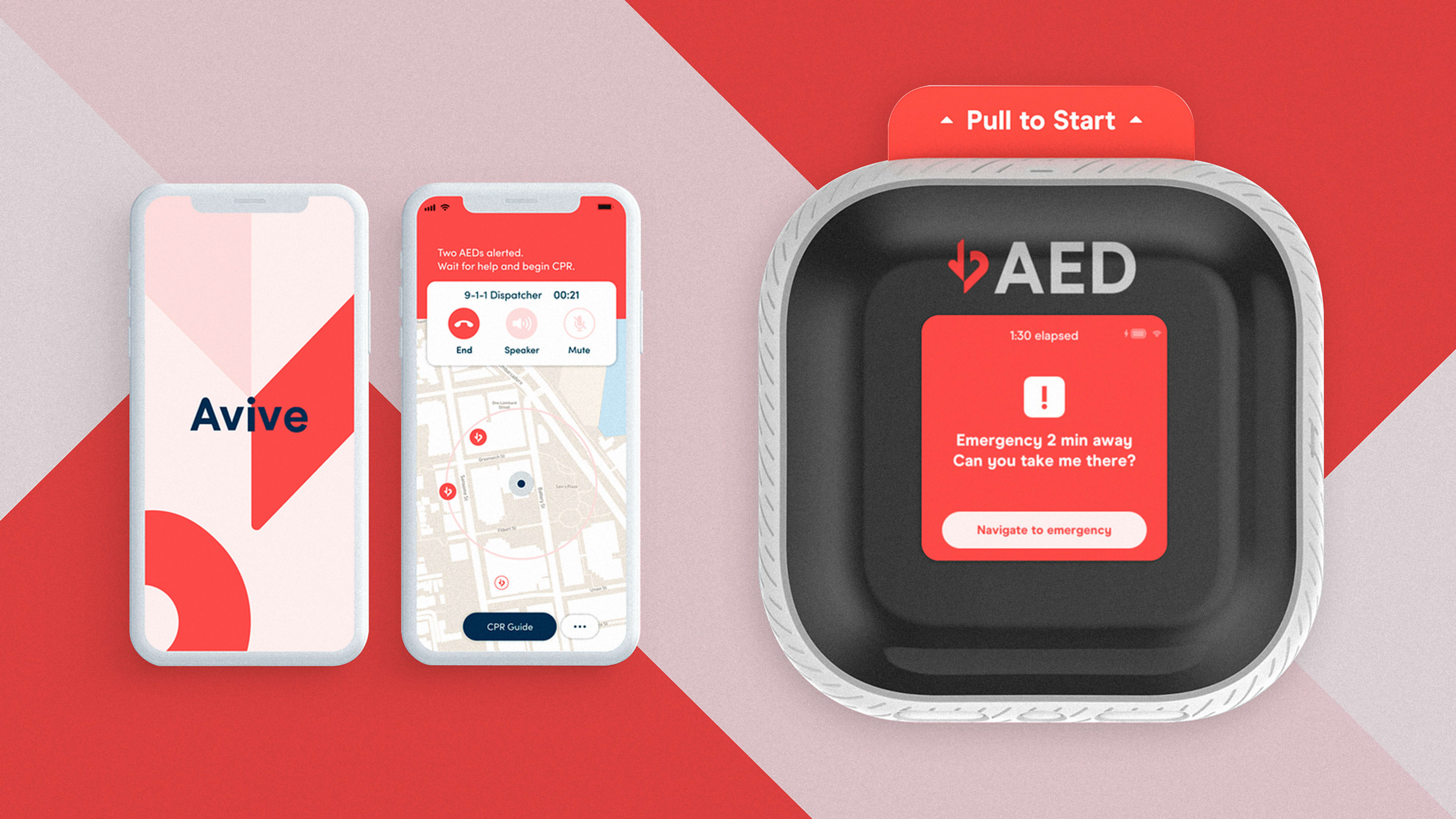

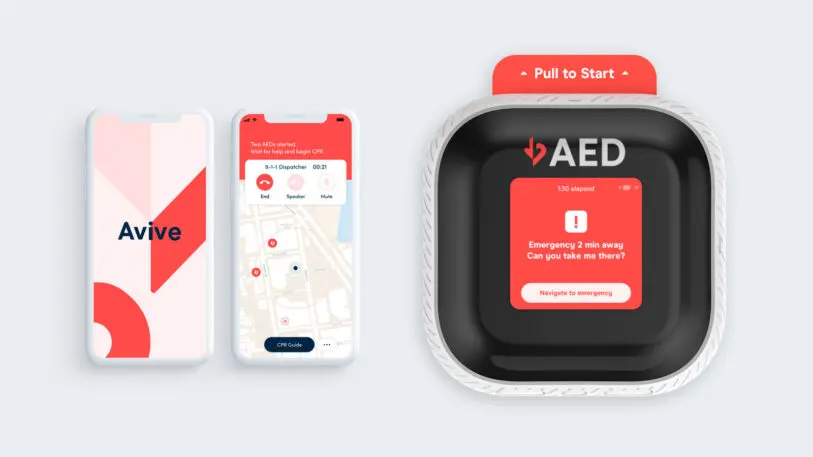

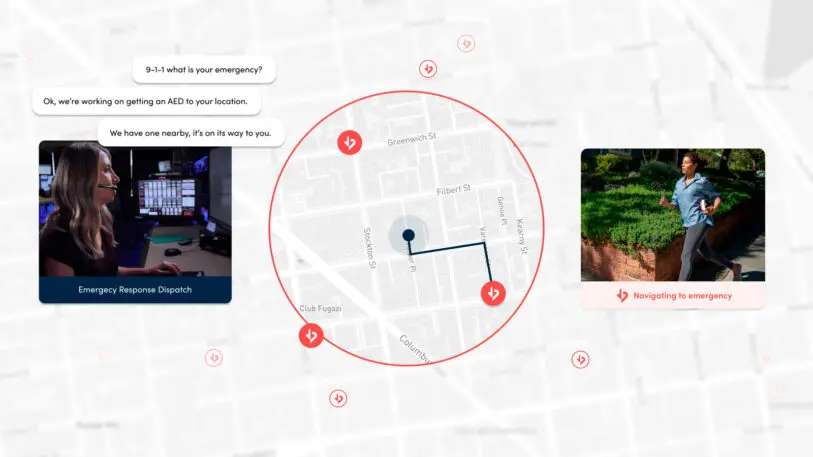

A startup called Avive believes they’ve developed the answer. Designed by the San Francisco design firm NewDealDesign, it’s a tiny AED that’s more like a typical gadget than a medical product. It sits on your wall, much like a thermostat when not in use, and it can be tossed in a bag if you want it when you go out. Of course, it has been tested and refined to be easy to use. But its biggest feature is a sort of neighborhood watch for heart problems. Because when someone locally calls 911 in cardiac arrest, the device can ping you with a map to their location—hopefully allowing you to arrive even faster than a paramedic. That is, assuming Avive can get through FDA approval, and enough local 911 call centers adopt the behavior.

As Amit explains, the entire experience had to be so clear that someone who’d never seen the defibrillator before could pick it up to save someone else’s life. They called this metric “time to shock,” and the studio actually went through two rounds of testing to validate it, in which laypeople were handed the device and asked to save the life of a test dummy. Because people can begin to suffer brain damage at three minutes and die by nine or ten, the AED had to be as fast-to-use as possible.

Initially, Amit says their time to shock was around five to six minutes: which is over the crucial three-minute barrier they were going for. By honing the device UI—which uses a combination of voice and onscreen prompts—they were able to get that average time down to two minutes or under.

This UX wasn’t just about clarity, however. The team realized they needed to address societal norms in a situation where seconds mattered—ensuring that when someone is lying unconscious, no clothing or other barriers are in the way of the electrodes touching their skin. “We used a female dummy, and one of the biggest hurdles people had was removing the bra—which is very important, because many bras have wires which can be difficult during electrical shock,” says Amit.

Once 911 was pinged for help, you’d hear a notification, see the person’s location on the screen, and with a button press, you could claim the job before sprinting out the door. Along the way, the device actually connects you to the 911 operator managing the case, to coordinate your efforts, or perhaps help you find the right floor of a city apartment.

For now, Avive needs to get their AED through final stages of FDA approval in order to sell it, and enlist 911 operations centers to support the product. Though even without the mapping functionality, it still appears to be the smallest, most approachable AED on the market (and its price will be competitive, costing something like you’d spend on a low- to mid-range smartphone).

“It’s not a low-cost consumer device, but it’s attainable,” says Amit. “Like we have a few fire extinguishers in the house—there are quite a few people who could afford that.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.