It’s probably no exaggeration to say that every urban planner dreams of a world in which parking lots don’t exist. They take up a lot of space (about one-third of land area in American cities), they’re not used as much as you think, and all of that pavement increases the urban heat island effect. So much of that space could be given back to people, but the process is slow, complex, and mired in zoning problems.

Eventually, the city manager used his executive authority to remove all zoning restrictions; but in March 2022, the Governor of Massachusetts deemed the state of emergency over, so the team had to go before the zoning board of appeals and seek a special permit in order to reopen for the summer. Of the six months they applied for, only three months were approved. And while the abutting supermarket asked for some of its parking spaces back last year, this isn’t because of parking. For Michael Monestime, then the executive director of the BID, “It all boils down to sound.”

“A story of compromises”

It’s a bit of a catch-22. Starlight is framed by a simple structure made up of Jersey barriers; a scaffolding frame; and a translucent scrim, printed with historic photographs, architectural sketches, and artwork curated by a local creative agency. Starlight won the city over because it was designed to be temporary and reversible: If they didn’t like it, it could be taken down, explains Matthew Boyes-Watson, partner of Flagg Street Studio and a principal of his eponymous architectural firm. So Starlight is noisy because it has no walls or insulation, but it has no walls or insulation because it had to be temporary.

It starts with balanced programming. “We’ve tried to make everything much more predictable; so if you’re a neighbor, you’re able to know, ‘When might I feel the impact, or when can I join in?'” says Nina Berg, the BID’s creative director (and also a partner of Flagg Street Studio). Together with local community partners, Starlight runs events five nights a week; but only two of those now feature amplified music, Fridays and Saturdays. “It’s a story of compromises,” says Monestime.

The operating budget for Starlight, which includes the installation, operation, and underwriting grants for organizers, has ranged from $490,00 to $560,000 per year—and every single event is free of charge.

From pop-up to permanence

To further alleviate the impact, the team has done a series of adjustments to the number of speakers and how they’re positioned. Boyes-Watson says they’ve also investigated acoustic paneling, “but you can’t overcome that challenge of how sound carries in what is essentially scaffolding and scrim.”

What needs to happen next is pretty obvious: The pop-up structure has to graduate and become a proper building. “We wanted to show that this city land could be deployed for something so much more than parking and to benefit of residents of Cambridge,” says Boyes-Watson. Now, the architect is quietly working on a more permanent solution, like a U-shaped building that would frame an open courtyard space. Except, the approval threshold for something like this is much lower. A permanent project would likely require City Council approval, numerous Requests For Proposals, a special permit, and a building permit—before construction can even begin.

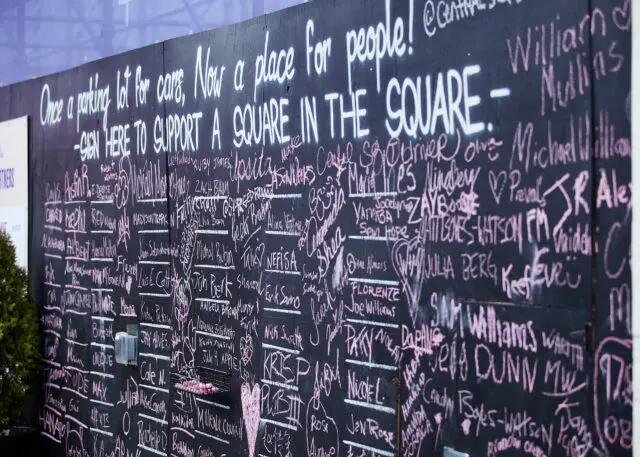

The fact that Starlight Square has just reopened for the third year in a row is proof that Cambridge can function without Lot 5. Because, at the end of the day, this is about changing behavior. “Every municipality has surface lots, and when you remove cars a lot of magical stuff can happen,” says Monestime. “People have been programmed that this is no longer a parking lot.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.