A Lviv-based team of Ukrainian software engineers have developed an online game called “Play for Ukraine” that crowdsources and gamifies participation in Dedicated Denial of Service (DDOS) attacks against selected Russian government and media websites.

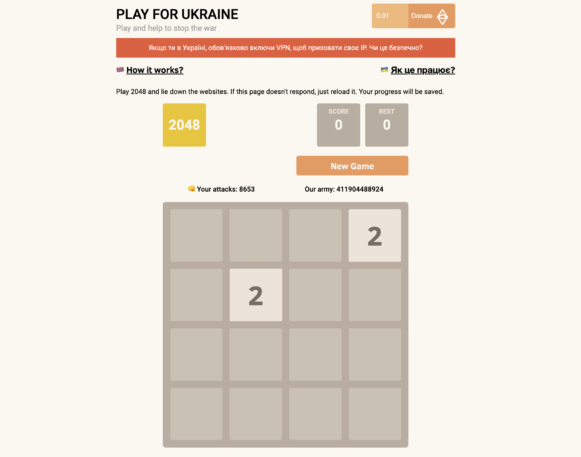

The game, which is based on the popular numerical puzzle game “2048,” is designed such that each move a player makes helps in a DDOS attack on a targeted web server. The game launched on February 28, according to the developers’ Twitter account. As of March 15, the developers say, 2,048 players had helped attack more than 200 Russian websites.

“Our main goal is websites that serve the Russian army,” the developers write on the game’s website. “We . . . rely on a steady torrent of automated traffic to knock a target websites offline.”

In a DDoS attack, an attacker normally uses malware to hijack a number of computers, which it then directs to continuously send requests to a targeted server until the normal operating of the server is disrupted or halted. Instead of hijacking computers, Play for Ukraine sends server requests to targeted servers as they voluntarily make moves in the game. The developers say that one user can send 20,000 server requests in one hour of gameplay, so players are obviously sending more requests than one-per-move.

For security and strategic purposes the game developers don’t divulge the names of the Russian websites they’re targeting. But they have reported several successes–that is, Russian site take-downs—via the Play for Ukraine Twitter account.

Is it legit? The developers say the game has been verified by the Ukrainian Cyber Police, a law enforcement agency focusing on cybercrime within the the Ministry of Internal Affairs.

Ukrainian Vice Prime Minister Mykhailo Fedorovwill in late February called on his country’s outsized population of software developers (estimates say there are 200,000 of them) to create an “IT army” to conduct both defensive and offensive cyber operations against Russia. The Lviv group who created Play for Ukraine says in the game’s FAQ that it intends to do more projects with the IT Army.

Play for Ukraine is just one of the cyberweapons developed by Ukrainian software engineers to wage a quieter war behind the more kinetic and violent one that’s slowly enveloping the eastern European country. They’ve created public safety apps, humanitarian aid apps, and cyberdefense apps.

Others have used their existing apps and infrastructure to engage in the information war around the conflict.

The popular social face swapping app Reface has a large Russian userbase, and the developers have sent more than 13 million push notifications to the devices its Russian users showing the real civilian damage caused in Ukraine by Putin’s military. This directly counters the continuous messaging of state-controlled media in Russia portraying the war as a small military incursion targeting “nazis” within the Ukraine government.

MacPaw (Mac productivity) and BetterMe (health coaching) have also sent informational push notifications about the war to the devices of their Russian app users.

Success in the cyberwarfare and information warfare dimensions of the conflict by Ukrainian developers could eventually weaken both the Russian military’s ability to fight and the support of the Russian public that’s vital to the continuance of Putin’s increasingly deadly war.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.