Rush hour in Copenhagen is dominated by people on bicycles: Around two-thirds of the city’s residents now bike to school or work instead of driving. That wasn’t an inevitable reality: Bikes were popular in the city early in the 1900s, but by the 1950s, as people got richer and moved to the suburbs, cars had overtaken bikes on roads.

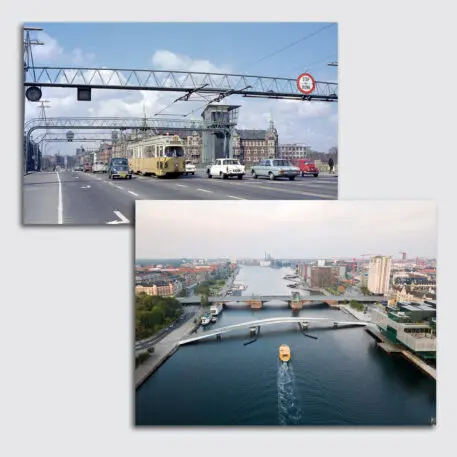

By the 1960s, city planners saw cars as the future and bicycles as outdated. They sketched visions to add new urban highways and take out bike lanes that some thought were a waste of space. But the global oil crisis of 1973—when oil prices quadrupled within a few days—helped push the city in a different direction.

Even before the oil embargo, when Middle Eastern suppliers stopped selling fuel to some countries because of a conflict in Israel, some Copenhageners were beginning to question the wisdom of following the American example of city planning. (At the time, Danish leaders visited American cities to see car-centric design in action; Americans now visit Copenhagen to see the opposite.) A proposed highway that would have paved over lakes in the city sparked protests. A busy street in the center of the city was pedestrianized, though the mayor at the time faced death threats for making the changes.

The oil crisis helped lead to faster changes in the 1970s. Driving was temporarily banned on Sundays because of the shortage of gas. “I remember, as a child, walking in the middle of the highway,” says Klaus Bondam, CEO of the nonprofit Danish Cyclists Federation. A growing environmental movement started talking about bikes as alternative transportation. The city eventually abandoned plans for some major new road projects, pedestrianized more streets, and banned through-traffic in other areas.

“Since the ’70s, the city has basically set aside money every year to expand and expand and expand the bicycle infrastructure of Copenhagen,” Bondam says. The changes accelerated further in 2005, when a new mayor was elected on a platform that championed cycling. Bondam was deputy mayor at the time.

“We started some huge investment schemes in more cycling infrastructure,” he says. “But I think more importantly, we moved cycling and cycling culture up on the political agenda.” The city also launched a marketing campaign to encourage more people to bike, with an “I CPH” logo and messaging about how cycling could cut congestion and pollution and help improve quality of life.

Even the most bike-friendly American cities don’t look like this. But it’s possible that the current spike in gas prices could help accelerate the changes that have started to happen in the U.S. over the last decade.

Copenhagen is unique in some ways. It’s compact, so biking anywhere doesn’t take long. It’s flat—although so is Silicon Valley south of San Francisco, with much better weather, and few people commute by bike there. Denmark never had a car-manufacturing industry lobbying for car-friendly roads (neighboring Sweden, home to Volvo and Saab, developed fairly differently.) Denmark also taxes cars heavily, making bikes even more attractive.

Still, Bondam says, change is possible anywhere. Take the example of Paris, where an influx of new bike lanes has quickly filled the streets with cyclists and made it look a lot more like Copenhagen. The full transformation takes time, he says.

“I think it’s important to understand that there’s no quick fix in this. It is an ongoing development that really needs political attention. It needs a public dialogue,” says Bondam. “It needs also courageous politicians sometimes that say okay, we’ll remove 100 parking spaces. Trust me, having been a politician, I know that it’s not an easy thing to do. I mean, people hate you. They literally hate you. But the funny thing is that, when you have done the changes, they kind of understand that it was probably the right thing to do. Because they suddenly see, it’s more quiet now. There isn’t as much air pollution. It’s actually safe for our children.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.