When COVID-19 vaccines arrived in 2020, humanity had engineered a modern miracle. But there was a catch: We quickly learned that the Pfizer vaccine had to be shipped at ultra-cold temperatures, as low as -130°F.

For most Americans, it was our first introduction to the logistical pains behind the “cold chain,” the chilly side of our supply chain–full of temperature-sensitive products ranging from frozen shrimp to insulin—a market expected to exceed $580 billion by 2030.

Now Ember, the company you might know from its battery-powered mugs that keep your coffee the perfect temperature, is making a big play on the cold supply chain. It’s developed the Ember Cube, what it claims to be the world’s first refrigerated, cloud-trackable shipping box. Despite being no heavier than a cardboard alternative loaded with freeze packs, the high-tech Cube is capable of keeping its cargo at 41°F degrees for up to 72 hours, even in desert conditions. It’s also built to be super durable—estimated to offer a decade of use.

[Image: courtesy Ember]The Cube itself would be less relevant if Ember didn’t already have its first client: Cardinal Health. Cardinal is one of the largest distribution companies in healthcare, doing $162 billion in revenue a year by shipping medical supplies, like prescription drugs, to hospitals and drug stores (CVS accounts for 30% of Cardinal’s business). The cold chain is part of Cardinal’s “specialty solutions” category, and represents 60% of specialty volume and revenue.

In an exclusive arrangement with Ember, Cardinal Health will begin using Ember Cubes in shipments later this year. As the project reaches scale toward the end of 2022, the companies estimate that the Cube will save 7 million pounds of packaging waste from landfills a year—in the form of single-serve cardboard, Styrofoam, and ice packs that temperature-sensitive medicines are shipped today.

Part of Cardinal’s impetus is that it predicts more drugs and treatments requiring cold temperatures. But they’re also being realistic about the shifting climate. “The environment is getting hotter and hotter as well, and [we need] to ensure we can handle these products the best for patients at all time,” says Heidi Hunter, president of Cardinal Health Specialty Solutions.

Developing the Cube

Today, Ember is a California company with 137 employees, and all of its products are some variety of smart coffee cup. But like many Silicon Valley types, Ember founder Clay Alexander doesn’t see his company as something that can be as easily pigeonholed by the market. It is a thermal management company, and Ember has more than 120 patents in temperature-control and other technologies that it would like to leverage across more industries.

More than four years ago, Ember board member Wyatt Decker was the CEO of the Mayo Clinic. He served as an inroad for Ember to meet with Mayo Clinic staff for a bit of market research.

Mayo Clinic doctors shared the pain points of handling boxes and refrigerating medicines. But a trip that doctors had planned to distribute vaccines in Haiti—a country full of remote villages where ice and refrigeration can be a rare luxury—led Alexander to begin work on his first refrigerated vaccine carrier. Alexander holds it up to the camera for me to see via FaceTime. It’s a white plastic pill that’s a little larger than your typical Bluetooth speaker. He pulls it open and reveals dozens of vials of vaccines stored neatly on a carousel. I’m reminded of the faux Barbasol container out of Jurassic Park, carried by Wayne Knight’s character to smuggle priceless dinosaur DNA out off the island.

“It was a huge hit [with doctors],” says Alexander. “Once we’d created this technology, I thought, ‘Okay, where’s the big, low-hanging fruit in moving this medicine around in the U.S.?”

A cold call with Cardinal Health, no pun intended, led to a surprising partnership. After seeing the device built for Haiti, Cardinal invited Ember to study its cold chain distribution center in Nashville. After that, Ember and Cardinal began developing the Ember Cube.

Shipping test Cubes around the U.S. quickly revealed that the plastic shell design couldn’t work. “Boy did it get scratched,” says Alexander. “Plastic just scratches! It looks really terrible after just a few shipments.”

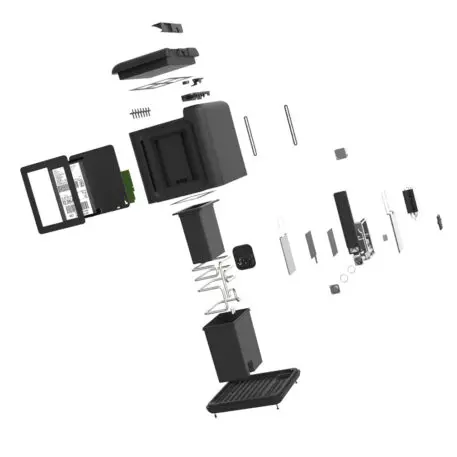

So instead, Ember reversed the design. They skinned the box with expanded polypropylene foam (EPP)—the same bouncy stuff used in rollers and other exercise equipment—and put harder structures inside. “The box acts like a rubber bouncing ball,” says Alexander. “If I drop this box on its corner, there are several inches of EPP foam, and it compresses like a spring, and bounces back.”

Instead, they built a hybrid cooling system. The Cube itself is vacuum insulated, like a Yeti cooler. Inside that is a phase change material. It’s a gel-like substance that starts frozen, but as heat inevitably enters the box, it absorbs that energy by turning to liquid. Cargo sits in a tiny compartment surrounded in this cold material.

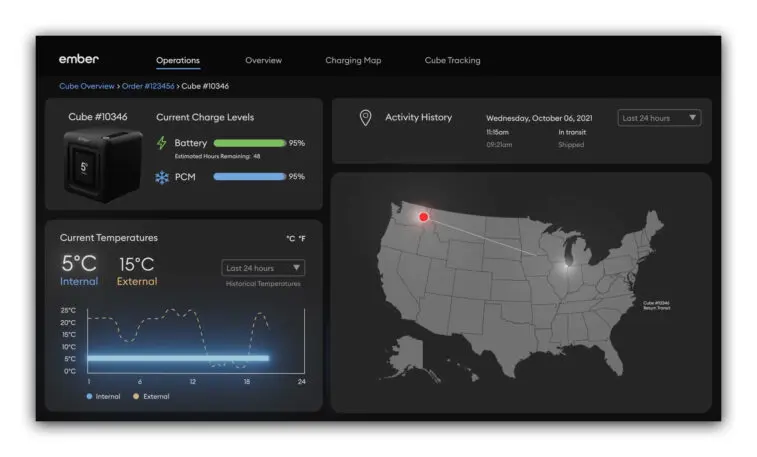

So far, that’s how the box stays cold. But what actively cools the box is a vented refrigeration system. When it’s being stored at HQ, it’s plugged in on a rack with breathing room. There, a mixture of water and ethanol pipes through the phase change material to freeze it. When it’s ready to ship, the box can stay cool without power for up to 72 hours. However, if a shipment gets delayed, Cardinal Health can see exactly where the Cube is on a dashboard via its cellular GPS. They imagine that, rather than letting the box get too hot and have its contents spoiled, anyone could pull it from a plane or truck, plug it in via a stock USB-C cable, and recharge it to make another 72 hours.

Fixing the UX of the supply chain

Truth be told, however, equally crucial aspects of the Cube’s design have nothing to do with cooling itself. Because when a medical professional receives the Cube, all they have to do is take out its contents, hit the single button on the front, and automatically schedule a UPS or FedEx return back to Cardinal Health.

How do they avoid printing labels? On the front of the box is an E Ink display, much like an Amazon Kindle, that automatically displays a shipping label. The label is generated in the cloud, via software developed by Ember. It addresses where the box needs to be picked up, because of the GPS inside.

A future full of Cubes

Ember and Cardinal have already proven out the Cube in a pilot study, but a second-generation version will begin testing in the spring, then scale up quickly, assuming things go well. For Ember, it’s an important moment, in which the coffee mug company shrugs off its existing reputation, and plans its own potential role in the future of the cold chain.

“The street cred that Ember’s going to gain by launching our technology in the healthcare space is . . . it is unmatched,” says Alexander. “Then I plan to move this technology into grocery and food delivery. . . . [We] just have to nail it.”

As for Cardinal, it sees the Cube as instrumental in its strategy to moving medicines of the future. As it’s built today, the Cube can transport the refrigerator-temperature Moderna and Johnson & Johnson vaccines. Future versions that Ember is prototyping will be able to that move goods at even colder temperatures, to support vaccines like Pfizer, and new biologics drugs. Hunter declines to share projections on just how much the Cube might impact their business, but sums up the potential in a quip instead.

“Two years ago, we didn’t expect that we’d have a vaccine that would require -70°C,” says Hunter. “But [next time] we will be ready.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.