After 58 years of service, the Metropolitan Transit Authority has now retired every single one of its remaining “Brightliners” (R-32 subway cars). Known for their shiny corrugated stainless-steel paneling, the Brightliners bid New York City farewell earlier this month, before they were taken by rail to be scrapped in Ohio.

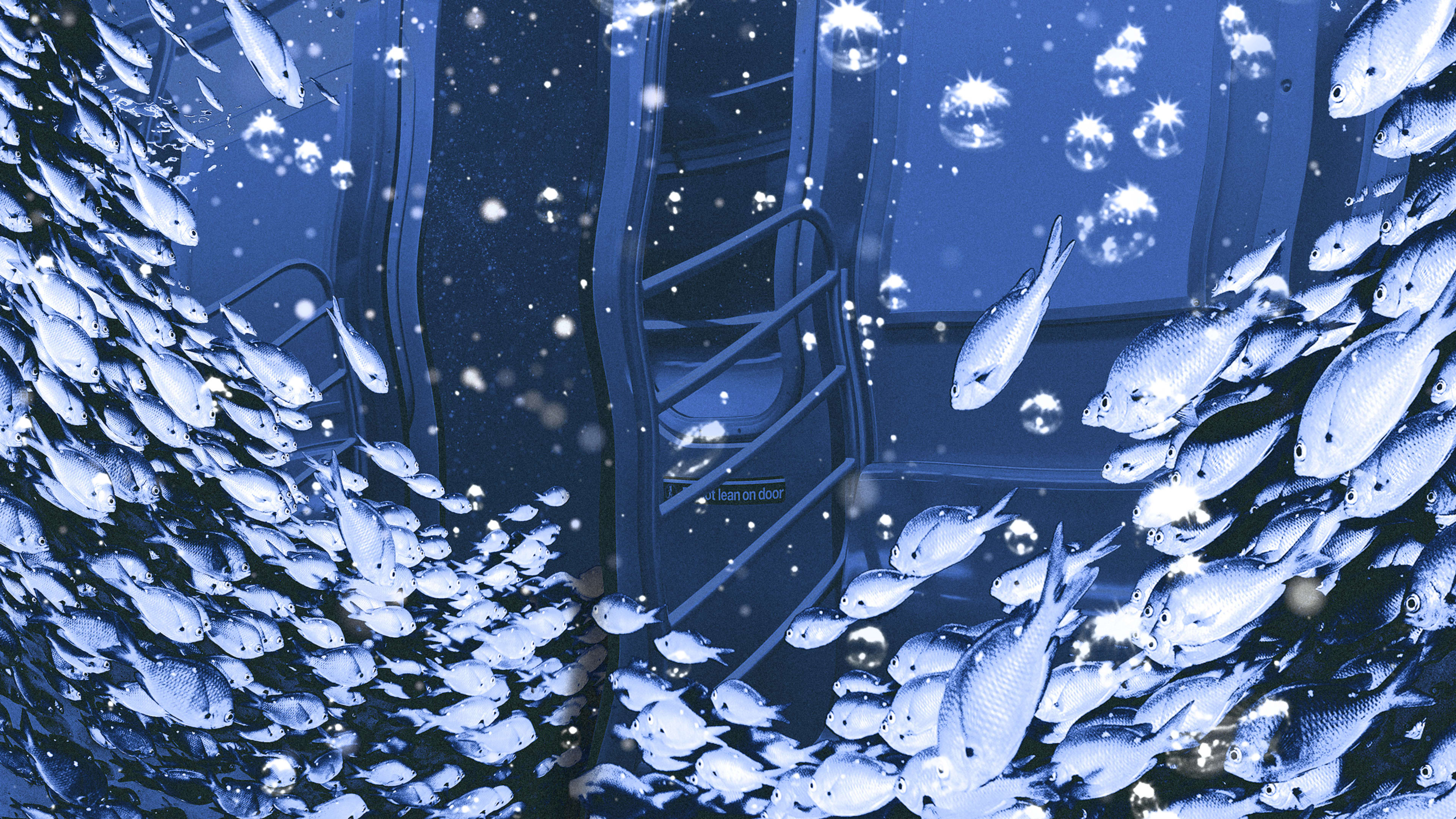

Most of the cars were retired more than 10 years ago, when more than 1,000 of them were shipped to coastal areas in Delaware, New Jersey, and Georgia and dropped on the ocean floor as part of an artificial reef program. Back then, artificial reefs were designed to boost recreational fishing, which in 2011 generated a whopping $15 billion in state and federal taxes. So the program made sense: The subway cars were welcomed by the fishing and scuba diving industries. Plus, the MTA saved millions of dollars it would have spent to scrap the trains.

The Brightliners were predicted to last underwater for more than 25 years, but they started to disintegrate only months after they were dropped. And that could have been the end of the story. But as climate change continues to deplete reefs and marine habitats across the country, artificial reefs have been growing as useful environmental tools. They can help restore lost habitat, enhance the marine ecosystem, and promote conservation efforts—as long as they’re the right size, right material, and placed in the right location.

By comparison, Brightliners were made of stainless steel. When the subway cars debuted in 1964, they were a mechanical and aesthetic innovation. The stainless steel made the train cars lighter on the tracks, but this worked against them underwater. Daniel Sheehy, an environmental consultant who’s been studying artificial reefs for more than 50 years, says the project failed for two reasons: first, because the trains’ envelopes were spot-welded, which formed a thin layer between the two metals that led to corrosion. Second, because the corrugated pattern made it easier for undercurrent waves to “grab on to” and further pull the stainless skin apart. “It is important that we learn from these mistakes and improve the process,” he says.

Artificial reefs date back to 17th-century Japan, where rubble and rocks were used to grow kelp and increase commercial fishing stock. In the U.S., where such underwater projects are mostly built for recreational fishing, the earliest recorded artificial reef dates to the 1830s in South Carolina.

In recent history, submerged shipwrecks like the famous SS Antilla in the Caribbean are the most common forms of artificial reef. But myriad other reefs have been made from oil rigs, streetcars, military tanks, and even underwater sculpture parks like the Reef Line in Miami, slated to open this summer. (The world’s largest artificial reef is made of 3D-printed ceramic and rests in the Maldives.)

Sheehy explains that a few things are necessary for an artificial reef to be successful. Surface area is key because it provides more room for encrusted corals and sponges, which in turn form habitats for various marine species. Weight matters, too—the heavier something is, the less likely it is to be turned over by undercurrent waves and hurricanes. That’s why tanks have been so effective. “Tanks were not meant to be taken apart,” he says. “They’re good for 150 years.”

As for materials, anything from concrete rubble to reclaimed culverts to damaged telephone poles can do the trick, as long as tires aren’t involved. In the 1970s, for example, more than 2 million passenger tires were bundled together with steel clips and dropped off the coast of Florida to expand the now infamous Osborne Reef. Except the steel rusted away and let millions of tires loose into the ocean. “They’re still picking up tires in Malaysia,” Sheehy says.

Even the best materials can be used in the wrong location. When a series of tanks were deployed off the coast of Maryland, they sank right through the soft sediment. By comparison, World War II tanks at the bottom of the English Channel, where the ocean floor is harder, haven’t budged.

In the end, it all comes down to the purpose behind the artificial reef. When natural reefs are damaged, artificial reefs can help restore lost habitat. But man-made reefs can be used for conservation, too. “If you put [artificial] reefs in an area and declare it a marine protected zone, you’re creating additional habitat,” Sheehy explains, noting, “A lot more thought needs to be going into what we’re doing in the ocean, and constructed reefs are part of it.”

In other words, it takes more than tipping a decommissioned train overboard.

Recognize your company's culture of innovation by applying to this year's Best Workplaces for Innovators Awards before the extended deadline, April 12.