The average person today will spend about 90,0000 hours of their life at work. Unofficially, due to increasingly blurred boundaries between work and home, that number may be even higher.

In exchange for that time commitment, employers traditionally provided financial security. Employees often traded freedom and flexibility for the peace of mind that comes from a consistent paycheck. Gig workers, on the other hand, accept much more risk in exchange for greater autonomy and independence.

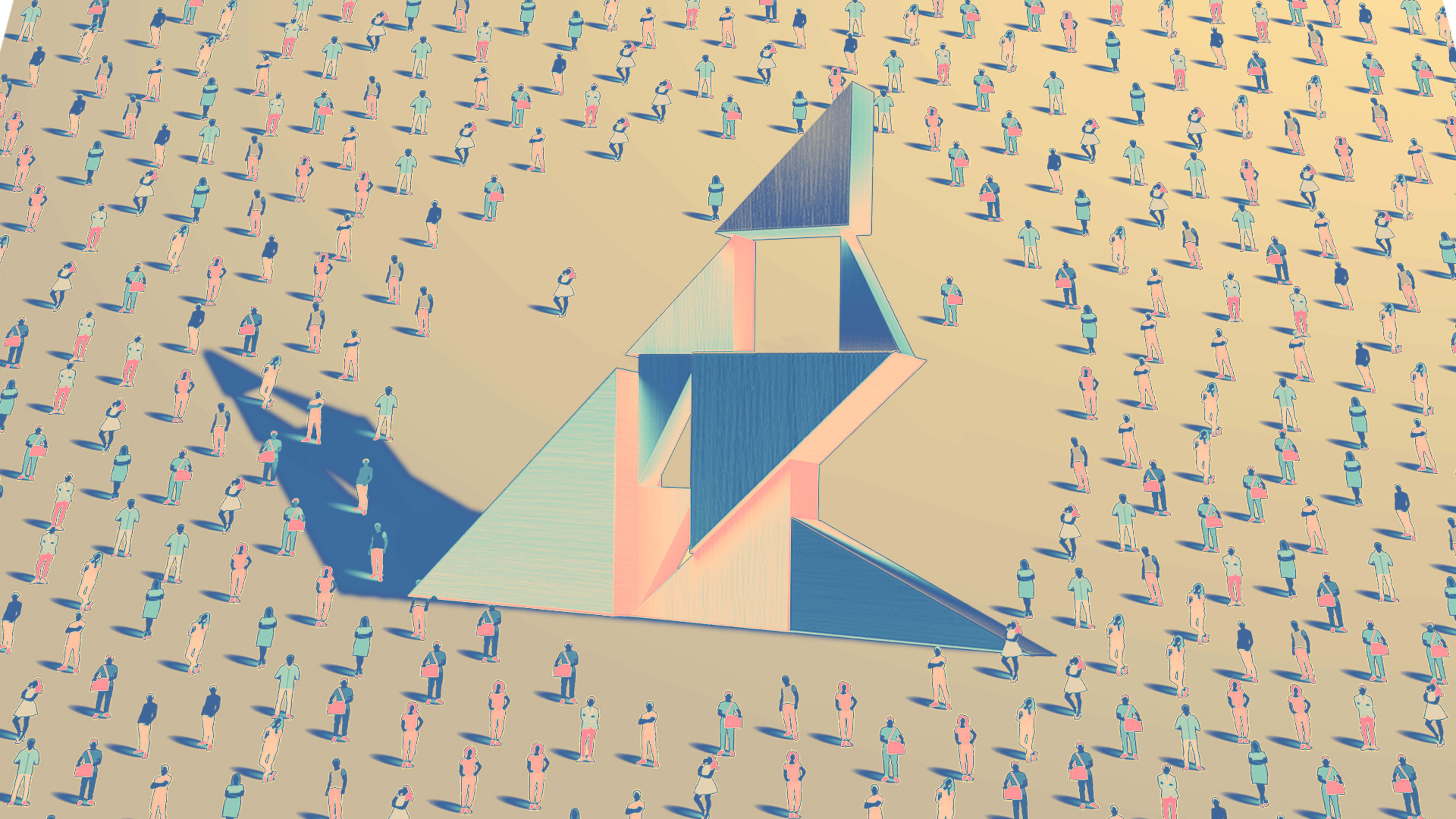

But the definition of a “job” is transforming, and a new generation’s expectations, combined with the dismantling of traditional organizational hierarchies, point to a new direction for the future of work, one that puts an end in sight for the longtime battle between freedom and security.

A brief history of jobs

Albert Walker was a gig worker. He was primarily a farmer, but to supplement his income and fuel his interests, he also took up some side hustles. He made cutlery and watches, and he had a particular affinity for inventing magic tricks. Magic was his passion, but he looked for ways to monetize it by building props, stage decorations, and accessories.

His life was not all that different from the developer working at Google who builds a website or app on the side, or who runs a YouTube channel, or sharpens knives in their free time.

The only difference is he lived in the 1800s.

Our current idea of a job is a relatively new concept. In the 1800s, about 80% of Americans were independent, self-sustaining, and growing their own food without support from an employer. Many could even be considered “gig workers,” like Albert—completing tasks for clients that matched their skillsets and interests.

In the early 1920s, the nature of work began to change. Factories opened, luring farmers into cities, and an influx of European immigrants created a marketplace for workers. The working class allowed factories to increase production and growth and drove the need for organizations and leadership that was not previously needed in small businesses and firms.

A new social contract was written. Workers could trade freedom for the security of 40 hours per week with steady pay. The Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) of 1938 established minimum wage, overtime pay, and recordkeeping. By the 1950s, the pendulum fully swung the other way and 90% of Americans had “jobs.”

Today, we are in the midst of another wave of change. According to Johnny C. Taylor, president and CEO of the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM), there haven’t been any meaningful alterations to the FLSA in over 80 years, and the legislation hasn’t kept up with societal and technological advancements. The rifts between ride-share services, their drivers, and regulators are signs of the growing pains. The rise of the gig economy, Gen Z’s behaviors and preferences, and the shift to an employee market are driving major changes to work as we know it.

Shifting demand

Gen Zs are the first truly digital natives, and they have vastly different expectations than previous generations. Their demands for work are shaped by five distinct characteristics:

- They prioritize financial security: SHRM’s Taylor explains that Gen Zs saw parents and older siblings struggle through the 2008 financial crisis and the global pandemic. They prioritize money and value financial security. They aren’t afraid to jump ship for a higher-paying offer.

- They prefer short sprints of employment: While past generations sought employment for 20 years to life, Gen Zs plan to stay for three years max. They are undeterred by being seen as job hoppers.

- They are digital natives: Millennials straddled the technology gap, but Gen Z is the first generation to have spent their whole lives around digital technologies. They understand the power of artificial intelligence and robotics and their implications for the future.

- They value earned leadership: Growing up using technology and social media taught them to respect earned leadership—follower counts mean more to them than job titles.

- They are lifelong learners: Familiar with disruption and rapid change, this generation knows that their future jobs may not even exist yet. They expect to change employers and career paths and are well-equipped to learn new skills.

Changes in supply

While Gen Z values are stimulating a new way to work, a number of market shifts on the supply side are setting the stage for that change to transpire:

- Organizations are lagging behind the marketplace: Ronald Coase’s Theory of the Firm told us that interactions between companies and workers had a cost. If the firm could coordinate the employment exchange at less cost than the market, it made sense to hire and retain employees. When the efficiency of the external marketplace is higher than the internal contract, the firm loses that transaction. Now, with digital hiring and gig working platforms, external marketplaces are getting more efficient and transaction costs are falling.

- The cost of hiring is reduced: Today, it only takes a few clicks to hire someone on Taskrabbit, Upwork, or Uber. 60 million people in the United States can be classified as gig workers, and 3 million are expected to be added every year.

- Hierarchies are breaking down: Former CEO of General Electric, Jack Welch, told us, “If the rate of change on the outside exceeds the rate of change on the inside, the end is near.” Slow-moving and change-resistant organizational hierarchies are not keeping up with the pace of change in society.

- New forms of organizations are emerging: Tom Malone, founder of MIT’s Center for Collective Intelligence, explains that humans make decisions together in five different ways: Democracies, Communities, Hierarchies, Marketplaces, and Ecosystems. While hierarchical structures are declining, organizations that design for communities, platform marketplaces, and ecosystems becoming much more prominent. For example, the Chinese home appliances company, Haier, grew from $15 billion after acquiring GE to $32 billion today. The company uses a distinct form of organization—without a central leadership structure. Its 4,000 microenterprises are self-managed and self-directed to serve end-users most efficiently.

While more employees are leaving behind secure employment and opting for gig work, the world of contracting and freelancing still leaves some gaps. These workers often lack security, benefits, and the sense of purpose that comes from belonging to a greater mission. Gig work is not yet protected by the FLSA and studies show that gig workers may feel a sense of loneliness and lack of fulfillment.

The most forward-looking, innovative organizations will be those that can give their employees the sense of freedom, flexibility, and passion of gig working with the purpose and support of serving a greater mission.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.