Tackling climate change involves not only slashing emissions, but starting to pull some of the billions of tons of extra CO2 out of the atmosphere. In the past, it’s been in the realm of near science fiction, largely confined to prototypes and theory. While some activists still argue that funding carbon removal will be used as a fig leaf to allow companies to avoid reducing emissions, this year’s dire IPCC report noted the necessity of using the tech as part of an overall climate change solution, and investments and advances in the industry skyrocketed this year.

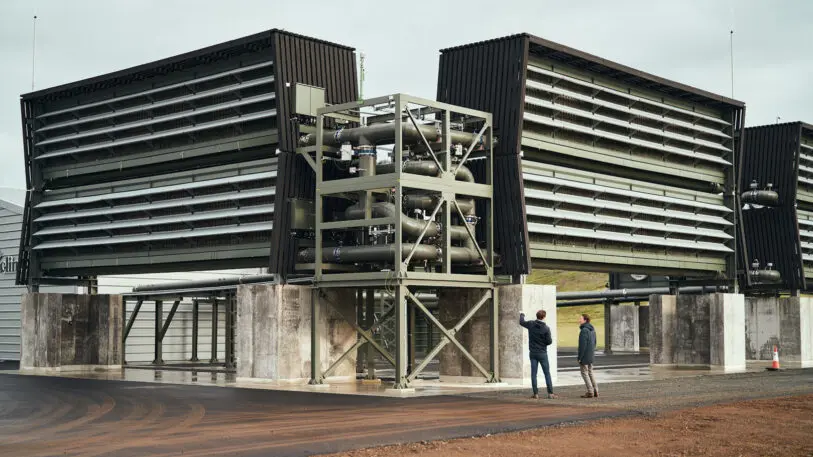

In Iceland, the world’s largest “direct air capture” plant opened in September, using giant fans to pull air through filters that capture CO2. The startup running the plant, Climeworks, partners with another company that pumps the CO2 underground, where it turns into stone. The facility can capture 4,000 tons of CO2 in a year. Carbon Engineering, another direct air capture company, worked with partners to begin the engineering of larger-scale facilities, including one planned for Scotland that will capture between 500,000 and 1 million tons of CO2 a year. Another large-scale direct air capture plant will begin construction somewhere in the southwest in 2022.

New government support can help bring down cost

The new U.S. infrastructure package commits billions to carbon removal—the largest government investment in the space so far—including support for four new direct air capture hubs, which each can remove at least 1 million tons of CO2 annually, in different regions of the country. The Department of Energy launched a new “Earthshot” program for carbon removal that aims to bring down the cost of the technology from as much as $2,000 per ton of captured CO2 to less than $100 a ton. (The program is modeled on the Obama-era Sunshot program, which helped lower the cost of solar power.)

Direct air capture machines are only one way to tackle the problem. A startup called Phykos, from former employees at Alphabet’s X, is building robots that can grow seaweed in the middle of the ocean and then sink the seaweed, potentially storing carbon at a large scale. (A company called Running Tide has a related approach.) Another startup is adding crushed rock to forests, where the rock can react with the rain and air to capture more carbon. Yet another turns agricultural waste into “bio oil” that can can be injected underground. Others are using technology to scale up more traditional methods of carbon removal like reforestation, including a startup run by Reddit’s former CEO.

After Microsoft announced last year that it planned to be carbon negative by 2030, and remove all of its historical carbon emissions as a company by 2050, it started investing in new carbon removal solutions to help the market grow and solve challenges like ensuring that data is accurate. The company’s $1 billion Climate Innovation Fund has invested in companies like Climeworks, the startup behind the new direct air capture in Iceland, and CarbonCure, which adds captured CO2 to concrete. The tech company Stripe started purchasing carbon removal from startups in 2020, and committed another $8 million this year, aiming to help bring down the high cost of new technology. Shopify spent millions on direct air capture.

The carbon removal industry still needs to grow exponentially: By one estimate, by midcentury, the world may have to remove 10 billion tons of carbon a year. That number may drop if some industries can move faster to decarbonize than expected—super-polluting industries like steel, concrete, and air travel may be able to transition to solutions like green hydrogen, for example, so less carbon removal is necessary to balance out lingering emissions. Even so, the industry is only a fraction of the size it will eventually have to be. But it’s finally beginning to be taken seriously.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.