The walls are usually open at the office of Los Angeles-based Lehrer Architects. Located in the hills near Silver Lake reservoir, the office was renovated in the early 2000s and features large windowed garage doors that can open to fully expose one side of the office to abundant fresh air. On days when the weather is nice, which in L.A. is most days, the garage door structures are lifted open. The walls might as well have never been there in the first place.

“You’re sitting in a sea of fresh air and literal healthfulness and psychic healthfulness,” says Michael Lehrer, the firm’s founder.

These kinds of open-air elements and indoor-outdoor blends have been recurring features in Lehrer’s L.A. designs over the years, including a 100-foot-long wall of windows that opens on the side of a gymnasium at the Stephen Wise Temple, and glass bifold doors that create indoor-outdoor classrooms at the Architecture and Design Institute. “Given that we’re in Southern California, if you don’t do something like this here, I don’t want to say it’s criminal—but it’s close to criminal,” he says. “If you can’t do and don’t do something where the weather is so gracious, then something is really not right.”

Now, after nearly two years of a global pandemic spread primarily through the air, built-in ways of keeping interior air fresh are becoming not just an L.A. design proclivity, but also a pubic-health imperative. More and more, fresh air and ventilation are being prioritized for the way buildings are designed and renovated. One of the most significant architectural legacies of the pandemic may be how buildings are learning to breathe again. Increasingly in Lehrer’s work, clients are calling for the kinds of large openings and fresh air access he’s been designing for more than 15 years. “There are few projects where there isn’t that opportunity,” Lehrer says.

Better airflow and safer ventilation systems are being integrated into buildings old and new. In New York City, one historic 1930s office building has just undergone a full interior renovation at a price tag of nearly $150 million. The remake of the McGraw-Hill Building in Midtown Manhattan included a thorough fit out of pandemic-aware ventilation, showing that even older buildings can adapt to changing conditions.

Designed by renowned architect Raymond Hood and completed in 1931, the 35-story building—which Ayn Rand called, “the most beautiful building in New York”—features green terra-cotta-tile cladding that turns blue on its higher floors, and at the crown, a stunning 11-foot-tall sign of the building’s name in art deco terra-cotta lettering. (Though the McGraw-Hill company left the space in the 1970s, its name remained as an indelible part of the building’s identity.) Recognized as a historic landmark at both the city and national levels, the facade of the protected building has been preserved, while the interior was transformed into modern office spaces. Controversially, the renovation led to the demolition of a retro-style lobby that many preservationists wanted to save.

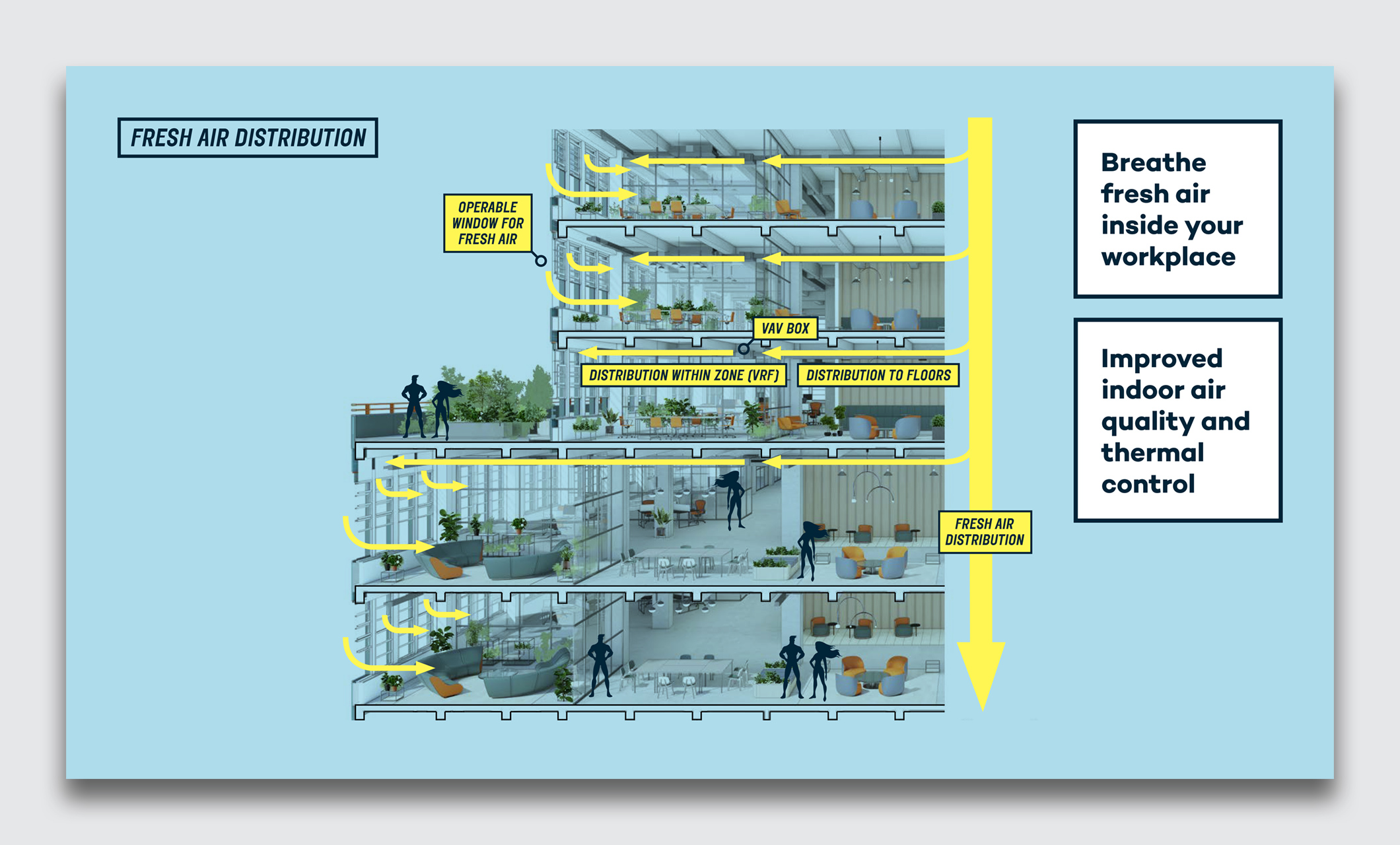

The renovation, which was led by Resolution Real Estate Partners and completed in September, features a water-cooled variable refrigerant flow system with a dedicated outside air service—essentially a super-efficient venting mechanism that pulls a large amount of filtered fresh air into the building on a continual basis and directs it only where needed.

While the project had been in the works since before the onset of the pandemic, the realities of the airborne virus led to changes in the way Resolution Real Estate Partners thought about moving air into and through the building. “Pre-Covid, what we were designing was based on flexibility for operation and cost effectiveness for the new tenants. Then when Covid came in, we were able to tweak it to get in the most fresh air possible,” says Gerard Nocera, managing partner of Resolution Real Estate Partners.

Instead of the typical HVAC system, relying on large-scale coolers on the roof of the building that control airflow to groups of entire floors, the new system can send cooled or heated air directly into specific rooms, reducing shared air across entire offices. So when one office is being used on a Saturday, for example, the building can send cooled air just into that one room instead of three or four largely empty floors.

It’s a more efficient way of controlling air temperature in an otherwise notoriously frigid and uncomfortable office environment. It’s also a better way of limiting how much air moves from one room to another before being sucked back into the filtration system. “You can literally cool one office at a time here and have fresh air coming to that office,” says Erik Caiola, director of construction at Resolution Real Estate Partners, which worked on the renovation.

For additional flexibility, the renovation also keeps intact the operable windows that run in horizontal rings around the building, true to Raymond Hood’s pre-air-conditioning 1930s-era design. Nocera says the pandemic has revived interest among office tenants of being able to reach over and open a window, rather than depending on a centralized air system. “I do think the future of office buildings is going to go back to what Hood did here. Rather than having the outside of the building be the most important thing, the inside is again becoming the focus,” he says.

Some of the world’s biggest companies agree. In new offices popping up across the U.S., companies are calling on their architects to break free from the sealed, air-conditioned boxes of the recent past and re-embrace the simple luxury of being able to open a window. In San Francisco, the recently completed Uber headquarters designed by SHoP Architects features many operable windows and a unique, fully ventilated semi-indoor space along its front sides, creating an airy space for workers to meet and travel from floor to floor.

Other big companies have made operable windows an essential part of their real-estate portfolios. When Amazon finalized the design of the cluster of new buildings for its second headquarters in Arlington, Virginia, windows that open were required. Amazon spokesperson Allison Flicker says there will be “thousands” of operable windows at the new buildings, which are now under construction. “Amazon has been building operable windows into its buildings for years prior to Covid-19 because we believe these features help our employees better connect to nature in an office setting,” Flicker says. That includes four of its buildings in Seattle, where the company says it has more than 6,000 operable windows.

The pandemic is likely just one factor in this renewed interest, but it’s also a powerful motivation for rethinking design, Lehrer argues. “Covid taught us the importance of fresh air and air movement and indoor-outdoor continuity. It’s also taught us the importance of place,” he says.

Designing spaces that are not only healthy but also places where people enjoy being is Lehrer’s ultimate goal. He’s hoping the pandemic is leading other architects—and the clients who commission them—to realize the multiple benefits of better airflow and ventilation.

“God forbid you do it for aesthetic and sensual reasons…at least, do it so you don’t get sick,” he says.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.