This article is about one of the honorees of Fast Company’s first Next Big Things in Tech awards. Read about all the winners here.

A woman named Hepburn is on my screen speaking my words, warmly, professionally, smiling in a sharp blue blazer, like a TV reporter or one of those improbably clear-skinned creators who make their living on YouTube. Then there’s a small clue: she mispronounces COVID like Ovid. The truth is, Hepburn lives in the cloud, and had been summoned just a few minutes earlier by Oren Aharon, the CEO and cofounder of Hour One, a Tel Aviv-based startup that builds human-seeming avatars, each capable of speaking some 20 languages. Watching her, I can’t suppress a small laugh.

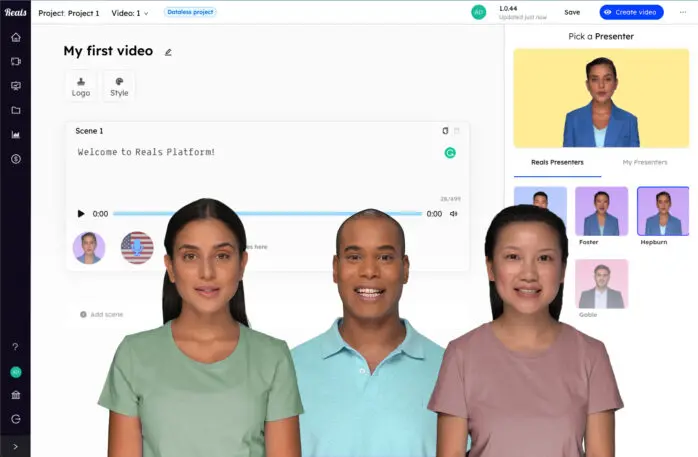

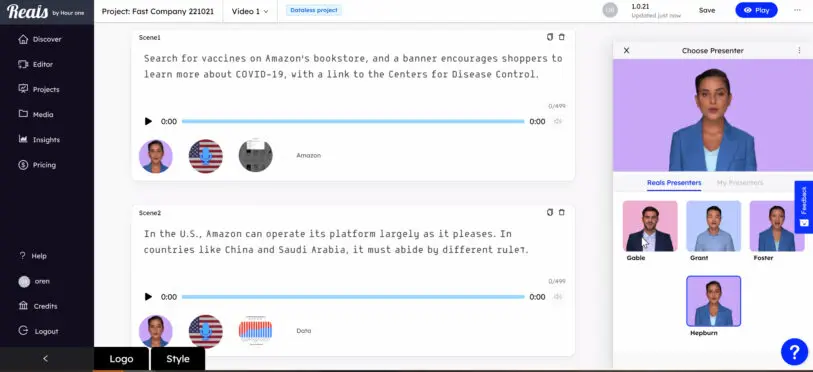

Hour One calls these deepfaked people “reals,” and without irony, because they are based on actual humans. Dozens of these talking heads are now doing tutorials, customer service, client presentations, interoffice communications, and silly videos on Cameo. Imagine a company-wide meeting, says Aharon: Why should the CEO record a presentation on video if his avatar can just do it? “You get something amazing in two minutes, you can send it to everyone, and nobody needs to waste their time,” he adds.

In 2017, the two entrepreneurs first saw an AI-generated Obama, and witnessed the start of a new era in which video gets automated by code. That was also the year that the work of an anonymous Reddit user named Deepfakes quickly came to represent all AI-powered threats to democracy. Nonconsensual porn was how it started, but synthetic media has since been used to falsely implicate enemies and steal millions of dollars. This year, voice clones for Anthony Boirdain and Val Kilmer sparked fresh ethical and economic concerns, particularly among voice actors worried about their jobs. Earlier this year, one actor sued TikTok for using her voice in its text-to-speech feature without compensation or consent.

Hour One is trying to put a happier face on all that, literally, by focusing on business uses and prioritzing the people behind the faces. And now that pandemic precautions have upended the workplace and the way we think about it—and companies devote billions to blockchains and “the metaverse”—the startup is riding a growing wave of interest in synthetic media. “The idea of, ‘You can’t do it from a studio anymore, so let’s try new technology’—that was really the perfect storm for us,” Aharon says.

The company of 15 raised $5 million in funding last year, and says it’s racked up dozens of customers. Berlitz is now using Hour One to “scale” some of its language teachers, and AliceReceptionist has tapped the company to welcome visitors to lobbies in English, Spanish, Arabic, and French Canadian. A German TV network hired its avatars to report soccer scores, and Cameo and DreamWorks recently worked with Hour One and the voice startup Lovo to debut its first “deepfake”: For 20 bucks, you can now get a jokey, semi-personalized greeting from the Boss Baby, the animated character voiced by Alec Baldwin. Cameo hints that more human celebrities may be coming.

Hepburn and most of Hour One’s characters are based on a diverse group of about 100 actual people, many from around Tel Aviv, who receive micropayments each time their likeness is used. Capturing a face using a high-resolution camera now takes only about half an hour. (Recording voices, as some opt to do, is a more time-consuming process).

To get Hepburn to read my story, Aharon opens a dashboard, pasted in an article I wrote, uploaded a few images, selected her from a gallery of talking heads, and added a voice. (The article was about, of all things, disinformation.) While the video is processing, he scrolls through other options: We can change backgrounds, select new camera movements, switch colors, text, or imagery, even get Hepburn to read the article in Mandarin. We could spin up hundreds of her at once.

“Not everyone is a YouTuber or a podcaster, and necessarily wants to spend all day recording themselves just to reach his audience,” says Hakim. “But [they do] want to create those personal connections.”

Seeing photo-realistic human faces “creates some kind of psychological effect where you basically feel the connection because you know this person is out there, this is a true person,” he says. And seeing a human “also creates a situation where people are saying, ‘Well, I could become a character, and there is a way to do it.'”

Aharon imagines this opening the door to what he calls “the character economy.” Eventually we could all become Reals.

“This is an asset that every one of us has, the likeness of us, the voice and the face, an asset that people will be able to use and scale, once digitized,” says Aharon. “There are what, 600 million people on LinkedIn? All of these people are potentially characters, potentially presenters.”

Advances in processors and GANs, or generative algorithmic networks, are cutting the time it takes to capture and render a talking head. They’ve also made it possible to render these faces instantaneously, and even make them interactive. In tests it’s done with the AI-writing system GPT-3, Hakim says that with only a few keyword prompts “the machine basically creates the entire scene.”

Generating substitute teachers

My Spanish instructor was realistic enough, at least enough to get to me to focus on my pronunciation, rather than on her computer-generated articulation. For Berlitz, Hour One made 13,000 videos of these deepfaked teachers, speaking English, Spanish, and German, in about 15 hours. The language-training company still offers online classes with human instructors, but digital teachers mean it can drastically lower production costs (and perhaps subscription costs), while still providing what its CEO Curt Uehlein called in a statement “a very human-centric experience.”

Still, it’s not clear if fake humans, even very realistic ones, can do the heavy lifting of an actual human teacher: Research has shown that even real humans communicating through a screen don’t activate the same parts of the brain associated with live social contexts. And it seems hard to spin a “human-centric experience” as good news for actual human teachers. Still, Hakim insists: “We are not looking to replace the jobs of workers. We are actually putting creative tools in the hands of people in the world of work, so they can actually focus on the creative process.”

The founders say they are mindful of other perils, too. While Hour One doesn’t let people dictate how and where their likenesses will be used, its ethics policy and agreements with customers and talent forbid any uses for what Aharon calls “extreme” things: adult entertainment, profanity, politics, “inappropriate ads,” self-harm, or “any opinion that may incite controversy.” For “known” personalities like XPrize founder Peter Diamandis, or the YouTube star Taryn Southern, both of whom have been scanned, any use must be personally approved.

The company is also labeling its videos to avoid deceiving audiences. My Spanish teacher had a small watermark in the corner of her video—the letters “AV”—but I saw no obvious explanation that this meant “altered visual.” A proposed bill in the U.S. Congress would mandate such watermarks, though experts say more protections are needed.

There’s a tension here: Even as it labels its characters as fakes, Hour One is also trying to make them realistic enough to trick us into feeling a human connection. Amir Konigsberg, a tech entrepeneur who sits on Hour One’s board, suggests this tension could be what makes its avatars so compelling: not because they’re human but because they’re obviously fake—but look so human. “The fact that it’s very realistic, very high quality, but also marked as clearly synthetic, that’s why it’s engaging,” he says.

This may be why I couldn’t help laughing a little at Hepburn and what she portends. We’ve crawled out of the uncanny valley into another strange place, where our brains are increasingly stuck between what we know and what we see. It’s nervous laughter.

Recognize your brand's excellence by applying to this year's Brands That Matters Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.