Before he was recently banned from Wikipedia, Techyan was one of dozens of volunteers preparing to speak at last summer’s Wikimania, the free-knowledge movement’s annual conference. Born in China’s northeast, he’d been editing Chinese Wikipedia since his early teens. As one of its three dozen elected administrators, he hoped his presentation would put a more positive spin on what, lately, had become Wikipedia’s ugliest battlefield.

Rather than the edit wars and personal threats that had come to define some of the Chinese edition’s hot-button political topics like Hong Kong and Taiwan, Techyan planned to talk about how his three-year-old user group, the Wikimedians of Mainland China, or WMC, had thrived. It had done so in spite of government restrictions, and without official acknowledgment from the Wikimedia Foundation, the nonprofit that hosts the site in over 300 languages and hands out millions in grants.

Then in July, weeks before Wikimania, an email from the Foundation landed in his inbox: His presentation had been canceled. “Weeks later, I was banned,” he says.

According to a September statement by Maggie Dennis, the Foundation’s VP of trust and safety, Techyan and six other high-level users were in fact involved in “an infiltration” of the Chinese Wikipedia. In an interview, Dennis said a monthslong investigation found that the veteran editors were “coordinating to bias the encyclopedia and bias positions of authority” around a pro-Beijing viewpoint, in part by meddling in administrator elections and threatening, doxxing, and even physically assaulting, other volunteers. In all, the Foundation banned seven editors and temporarily demoted a dozen others over the abuses, which Dennis called “unprecedented in scope and nature.”

Seasoned Wikipedia volunteers are familiar with harassment and vandalism, but Wikipedians in China have it especially hard, because the government blocks the site and makes accessing it a crime. Since the Chinese edition was blocked in 2015, millions of mainland Chinese have turned to Baidu Baike, a homegrown, for-profit, Party-sanctioned alternative. But as with the dedicated mainland users of blocked apps like Instagram, Telegram, and Twitter, the prohibition hasn’t deterred hundreds of volunteers, who tunnel through the Great Firewall with VPNs, and now make up a small but die-hard part of the Chinese Wikipedia community. Fast Company is only identifying users by their Wikipedia usernames to protect their safety.

Despite China’s blockade, the site remains one of the ten most active language versions of Wikipedia, thanks largely to growing numbers of editors based in Taiwan and Hong Kong. And amid acute worries over China’s influence in both places, the community’s mix of users and viewpoints has grown increasingly combustible. In 2014, when mainland editors were in the majority, there were few references to the Hong Kong protests; more recently, swarms of “pro Beijing” editors and “pro democracy” editors have battled over how exactly to depict those and simliar events. Were the students at a particular rally in Hong Kong protesters or were they rioters? Is a state-backed news outlet a reliable source?

In some cases, the Foundation found, the fights had spread beyond online abuse and harassment into real-life threats, and worse. But because it released few details about the editors’ abuses, citing privacy concerns, the Foundation left many editors to speculate. On talk pages, in community chat rooms, and in media coverage, “pro-China infiltration” suggested an organized propaganda campaign, part of Beijing’s ongoing efforts to shape its image online. But such attributions are notoriously hard to make, and despite widespread evidence of China’s efforts to burnish its image online, Dennis says there is no evidence the banned editors were backed by the government.

Exclusive exchanges with Techyan, interviews with editors, and a review of records and recordings from the last 4 years suggest more personal motives. Techyan and his WMC colleagues liked to defend Beijing’s point of view, but they also liked their influence over the Wikipedia community; and a pro-China stance allowed them to more easily fly under the government’s radar. To protect their fiefdom, they sometimes resorted to personal threats, harassment, and assault.

“So,” Techyan told his colleagues about the beaten editor, “he stopped [editing] for a while.”

In blog posts and emails to Fast Company, Techyan rejected claims of “physical harm” and said the Foundation’s bans amounted to censorship and “discrimination,” and were based on politically motivated complaints from adversaries in Hong Kong and Taiwan. He said he could “barely” remember the 2018 meeting or the assault. (Fast Company is only identifying volunteers by their usernames.)

According to Techyan, he and other banned mainland editors are now building their own encyclopedia, starting with a “hard fork” of Chinese Wikipedia—a copy of the encyclopedia as it stands, which they will then edit and expand independently. The site, which he says already has 400,000 articles, is designed to be accessible within China, even though that will mean obeying government censors.

“The Foundation’s Office Action directly affected 20, but it pissed off many more—among them, software developers, server maintainers, professional encyclopedia writers, local history enthusiasts,” says Techyan. By neglecting the mainland Chinese community, he says, the Foundation had failed its knowledge-preserving mission. “If the WMF isn’t going to do this for us,” he says, “we have to take things into our own hands.”

The controversy even spilled into strident op-eds in Chinese state-backed media, where Wikipedia is rarely discussed. Citizens on the mainland were crossing the Great Firewall to access Wikipedia, one commentator acknowledged, but this was patriotic work that “has aroused the resentment of some Wikipedia users and foundations in Taiwan [who] . . . only hope that the China introduced by Wikipedia is the ‘chaotic, backward, and authoritarian’ country rendered by foreign media.'” Another article, published on the WeChat account of the Beijing-based Global Times, blamed the bans on one overseas Chinese pro-democracy editor in particular, sharing his name and personal photos and labeling him a “traitor.” Last month, Techyan said, he and another pro-Beijing editor were also doxxed on Wikipedia’s discussion pages.

“Sharing information is not always seen as a neutral act, depending on where you might live,” says Maryana Iskander, Wikimedia’s incoming CEO, who will take the reins at the San Francisco-based organization next month.

Suddenly, the Foundation’s bans and penalties had knocked out a third of the Chinese edition’s administrators.

While the Foundation has no official presence in China, it has funded Chinese Wikipedia projects with volunteers elsewhere. Still, several volunteers, reluctant to speak on the record, said it had been slow to act on years of complaints about abuse. “This was long overdue,” the Taiwan user group wrote in a letter.

Dennis acknowledged the Foundation had fallen short in its ability to address its “human rights impact” and to communicate with Chinese users. At the time of its investigation, for instance, Wikimedia didn’t have a fluent Mandarin Chinese speaker on its trust-and-safety staff. (Elise Flick, a Foundation spokesperson, said in an email that Wikimedia “has added in-house Chinese language engagement support as of mid-October.”) In her September statement, Dennis pledged to help Chinese Wikipedia rebuild in the wake of the bans, and apologized to the community. “You have not had the service you’ve deserved,” she wrote.

One challenge for Iskander will involve deciding how hands-on the Foundation should be as it protects a project that’s long been defined by grassroots self-governance. It’s because of that structure that the Foundation typically leaves much policy-making and policing up to each community. While Wikipedia has hundreds of thousands of users, until September, the Foundation had only issued 86 bans since 2012, and typically only one at a time. Suddenly, the Foundation’s bans and penalties had knocked out a third of the Chinese edition’s administrators.

“Given how much pride Wikipedia takes in being a global, open, and inclusive community, this decision [to ban editors] must have been really difficult for them, and shows how serious the challenge is that Beijing is posing to open societies,” says Lokman Tsui, a Hong Kong-based fellow at cybersecurity watchdog group Citizen Lab. “Wikipedia is the latest organization that has to struggle with this question, but it won’t be the last.”

“Just Report the Hong Kong editors”

China is home to the world’s largest population of internet users and to the world’s most sophisticated apparatus for policing them. But amid mounting efforts to shape the country’s image, Xi Jinping’s government has ramped up digital regulations with increasingly punitive zeal. Following a 2017 law that codified digital crimes, authorities now regularly solicit tips from the public about misbehavior online, and in some cases arrest those who access blocked websites, or use social media to, among other things, “slander” government officials or “malign” national heroes.

China’s Wikipedia users are also under increased scrutiny. There are no reliable data about internet-related arrests, but reports of detentions have circulated in encrypted chatrooms and discussion pages for years. One rare public acknowledgment came in October 2020, when police in Zhejiang said a man had been arrested because, for months, he had used a VPN to gain “illegal access to Wikipedia to obtain information.”

It wasn’t always so hard to be a Chinese Wikipedian. The Mandarin Chinese version of Wikipedia was born in 2001, just a few months after the English version, and got its first article the following year, on mathematics. By 2004, it had bloomed into a bustling community and was even receiving praise in state-run media.

In Hong Kong, where the Beijing-backed government has suppressed civil society, Wikipedia is still accessible and legal.

Beijing’s efforts to influence Wikipedia even extend to the United Nations. In October, for the second year in a row, Chinese officials blocked the Foundation’s application for observer status at the UN’s World Intellectual Property Organization, keeping Wikipedia out of global discussions around the sharing of information. The lone dissenting vote, a Chinese official explained, was because Wikipedia contained “a large amount of content and disinformation in violation of [the] ‘One China’ principle.” What’s more, he added, the Taiwan Wikimedia group had been “carrying out political activities . . . which could undermine the state’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.”

China’s digital suppression has been part of a global trend. In its latest report, published in September, the nonprofit Freedom House noted, alongside global efforts to regulate big tech platforms, “a record-breaking crackdown” on freedom of expression online: In at least 20 countries, governments suspended internet access, and 21 states blocked access to social media platforms, most often during times of political turmoil, such as elections and protests. In 56 countries, officials arrested or convicted people for their online speech. In a recent study on internet blockades, Google’s Jigsaw unit noted that what “was once a seemingly isolated problem has exploded” as a way for governments around the world to silence dissent and stifle democratic participation.

In Hong Kong, Wikipedia, like most other foreign websites, is still accessible and legal. But a new Beijing-backed national security law, instituted last year after months of massive protests, has given police new powers to smash civic groups, shut down independent media, and compel activists to erase their online presence. The law has also led to new internet blocks, including of certain websites related to Hong Kong’s independence movement or hosted by the Taiwanese government.

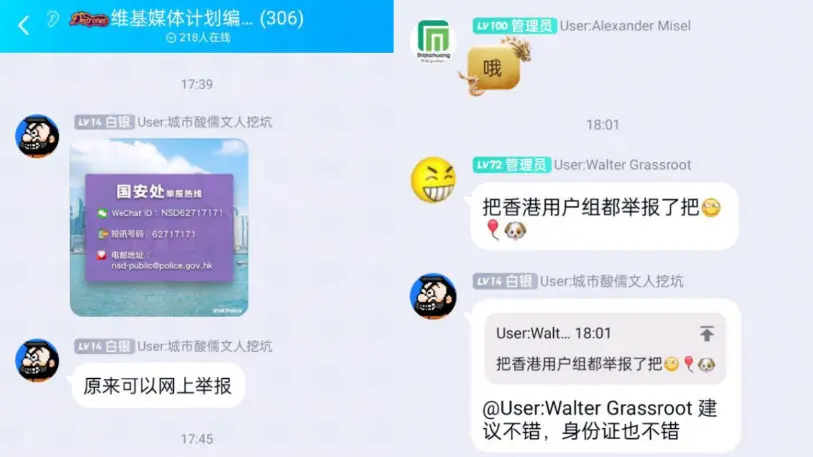

Wikipedians in Hong Kong have been on alert. In July, some China-based editors were seen discussing contacting the Hong Kong police. “Just report the Hong Kong editors,” one mainland user, nicknamed Walter Grassroot, wrote in a chat room, after someone shared the details of the Hong Kong public security bureau. “Nice idea,” said another, according to screenshots of the incident. “And their ID cards would be great too.”

Police, violence and bad apples

The problems in the Chinese Wikipedia community date back to 2017, the year the Wikimedians of Mainland China was founded, according to one longtime former editor. That summer, a number of pro-Beijing editors won election to administrative roles, which are responsible for shaping policies, protecting articles, and policing users. “The [WMC editors] elected more of their users to become admins, bureaucrats, and even oversighters [with higher data-access privileges],” says the former editor, a Chinese citizen who now lives overseas and is not being identified for safety reasons. During administrative elections, there were unusual spikes in votes for “pro China” users from sock puppet accounts. Harassment by certain editors went unpunished.

“The atmosphere for discussion grew worse,” the editor says. “Personal attacks from their group were not stopped but encouraged. People who dared to point out their issues were retaliated against.”

In January 2018, three members of the WMC physically assaulted a fourth after a meetup in Beijing. The victim had angered WMC leadership for telling the Taiwan user group that Techyan planned to meet Wikimedia Foundation officials in San Francisco. The Foundation later canceled the meeting.

The former editor said the victim had also publicly disclosed that two WMC members “had been forced to ‘drink tea’ by the government because of a planned meetup,” using a euphemism for being questioned by the police. Two Wikipedia user meetings were canceled as a result of the police incident, and WMC administrators later sought to censor any discussion of it. (One deleted discussion has been archived on the Wayback Machine.)

Though Techyan did not respond to specific questions about the assault, he says the WMC had already expelled some members for misbehavior. With hundreds of members attending meetups across China, “it is reasonable that there are a few bad apples,” he says.

Last year, as an editorial war raged over articles related to Hong Kong’s political crises, the authorities helped tip the scales even more. That April, Hong Kong police raided the newsroom of the local newspaper Apple Daily, arresting its publisher and editors, ordering its accounts frozen and its archives scrubbed. In an instant, the government had not only snapped away a legendary source of independent journalism, but also suddenly deprived Wikipedia editors of a key editorial building block. (While its opinion coverage is not allowed in Wikipedia, the paper’s news stories are considered reliable sources.)

In disputes over Hong Kong-related articles, the WMC and other pro-Beijing Wikipedia editors now had new ammunition to question the paper’s reporting. User “Walter Grassroot” temporarily deleted every Apple Daily citation. (Administrators later blamed it on a bot.) Others pushed for the inclusion of more state-backed news sources for articles about events such as the 2019 attack on protesters at the Yuen Long MTR station.

The reliable sources problem extends to the English edition, where the state-backed China Daily currently boasts some 6,000 citations. That’s because a small majority of users have deemed it a reliable source—CGTN, the state broadcaster, is not one—as a growing crackdown on journalists in China has left Wikipedians with few other options.

“[I]f there were better sources for China, then the China Daily would be deprecated entirely,” one English-language editor explained in a recent discussion, “but a narrow majority . . . feels that there are so few good sources for China that it’s needful for us to lower our bar.”

How to capture an encyclopedia

There are more insidious ways to influence Wikipedia content. English-language Wikipedia is edited once every 1.9 seconds and maintained by about 5,000 “extremely active” volunteer editors. But Wikipedia’s 300-plus non-English versions are far less policed and, so far, more vulnerable to manipulation. Half of its global editions have fewer than 10 active contributors. The result can be something like what happens on social media platforms, where policing dangerous content in non-Western languages has lagged dangerously behind the size of their respective audiences.

It’s highly likely that government operatives meddle with Wikipedia.

The failure of the Croatian edition, according to the Foundation’s first report on disinformation, published this year, “points at significant weakness in the global Wikimedia community and—by extension—Wikimedia Foundation platform governance.” This weakness, its unnamed author noted, could harm “public and regulatory confidence” in Wikipedia’s self-governance model, a problem that’s “increasingly important to resolve in the light of heightened regulatory scrutiny of user-generated platform models, including Wikipedia.”

Capture isn’t just a problem for seemingly small editions of Wikipedia. The Japanese edition is the second-most visited edition after English but has relatively few active admins—about 41 compared with English’s 1,100. Many of those admins have been protecting ultranationalist narratives and allowing the whitewashing of military war crimes, such as the massacre in Nanjing.

“The Foundation’s hands-off approach may have worked for the English version of Wikipedia,” researcher Yumiko Sato told a recent Wikipedia conference. “But many non-English versions need to be monitored to safeguard their quality.”

Read more: Non-English Wikipedia has a misinformation problem

Sato, who has studied the Japanese Wikipedia’s problems, says its capture wasn’t carried out by an organized cabal of right-wing editors, but is rather the result of a “dysfunctional community” gradually and haphazardly built by “bullies and bystanders.” But, as the Foundation’s report warned about the Croatian Wikipedia, a “more resourced and better-organized attempt to [introduce disinformation] could be harder to detect and protect against.”

It’s highly likely that government operatives meddle with Wikipedia, and the idea of the Chinese government standing up teams of editors to burnish its image there isn’t just a Western fantasy. “China urgently needs to encourage and train Chinese netizens to become Wikipedia platform opinion leaders and administrators [who] can adhere to socialist values and form some core editorial teams,” media scholars Li Hao Gan and Bin Ting Weng recommended to Party leaders in a 2016 paper in the journal International Communications.

Given its growing role in our web searches and AI systems, even subtle changes to Wikipedia along cultural or political lines can have deep ripple effects. In a study this year by researchers at UC San Diego, a language algorithm trained on uncensored Chinese Wikipedia represented “democracy” closer to positive words, such as “stability,” while another, trained on Baidu Baike, represented “democracy” as closer to “chaos.”

But tampering with Wikipedia isn’t as simple as a Facebook op. Controversial entries are placed under protection and careful scrutiny by teams of humans and bots. And corrupting the system would require cultivating enough veteran elected editors like Techyan.

“The Chinese government cannot reasonably ‘infiltrate’ one-third of all Chinese Wikipedia admins,” Techyan says. To become an administrator, Wikipedia users must have made at least 3,000 edits on Wikipedia and win their positions in elections with added protections. “It’s not like infiltrating Twitter, where the Chinese government can just register a bunch of accounts and start spamming misinformation.”

In any case, Beijing likely doesn’t need to directly back Wikipedia editors in order to influence their activities. When it can’t rely on patriotic volunteers fervently promoting its point of view, it can order arrests.

“Community ‘capture’ is a real and present threat,” Dennis wrote in a statement. “I do think that the risk [of capture] is greater than ever now, when Wikimedia projects are widely trusted, and when the stakes are so high for organized efforts to control the [personal] information they share,” she told me.

In the weeks before the bans on Chinese Wikipedia, the Foundation also temporarily removed privileged data access for some editors, not because they were suspected of involvement in the “infiltration” attempt, but because their access made them potential targets of abuse, either by WMC members or the government.

“What we have seen in our own movement includes not only people deliberately seeking to ingratiate themselves with their communities in order to obtain access and advance an agenda contrary to open-knowledge goals, but also individuals who have become vulnerable to exploitation and harm by external groups because they are already trusted insiders,” Dennis wrote.

Sato says the Foundation could do much more to address the threat of community capture on smaller editions, including by simply hiring more native-language speakers. One grander idea would unify Wikipedia across languages, so that a change in one edition could be automatically registered in others. A related concept is already taking flight in a backend project called Abstract Wikipedia. And as of this month, one million articles now offer links to automatic translations of more comprehensive articles in other editions.

Unifying articles across languages may be a thorny solution—knowledge is often legitimately contested across cultural lines—but Sato thinks that, at least for certain fraught topics, unifying the editing process “on a global scale will probably be better for us [on English Wikipedia] too.”

Read more: How 9/11 turned a new site called Wikipedia into history’s crowdsourced front page

Meanwhile, Techyan and other banned editors are aiming in the other direction, building their own Wikipedia, which will be tailored to appease government censors so that anyone on the mainland can access it.

“I’m looking at roughly 40 editors who we could siphon from Chinese Wikipedia to work exclusively for the hard fork, and dozens more who work for both projects,” says Techyan, who recently returned to China from the U.S. to help manage the effort. He says he’s now in the process of establishing a for-profit company, a requirement to obtain necessary government approval, and negotiating with an unnamed “Chinese tech giant” about the terms of a possible “partnership.” The site already has 400,000 articles, he says, most adapted from Chinese Wikipedia.

Previous spin-offs like Citizendium and Conservapedia suggest this will be a difficult struggle. Techyan isn’t fazed. Over 40 Chinese Wikipedia editors have already joined the new project, out of what he says are 200 active editors in total. “What’s more, we haven’t even counted the new mainland Chinese editors who will be joining us in the future,” he says, “since our hard fork is available without needing a VPN.”

Wikipedia’s open license permits anyone to fork Wikipedia content into a stand-alone version of the site; but a splintered, censored version of the encyclopedia violates its basic vision, of shared knowledge and civil deliberation across political and ideological lines. While “Wikipedia is not a democracy,” one of its precepts says, it may be the closest thing we have to a digital one. And as the internet moves in the other direction, increasingly fragmented and authoritarian, polarized and misinformed, fueled by for-profit scams and sectarian politics, keeping this democratic system will mean fighting for it.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.