The 12-foot-long strip of concrete running through a new park in Shanghai is one clear remnant of the land’s previous and radically different life. Originally laid in 1948, this line of concrete was once part of a long, flat runway for the city’s Longhua Airport. After it closed in 2011 and a district-scale urban redevelopment project began rising along its edges, the concrete runway went from being a crucial piece of transportation infrastructure to a vast and seemingly useless relic.

This is one of the latest examples of outdated transportation infrastructure being reborn into lively public spaces. New York’s High Line and Chicago’s 606 transformed disused rail lines into city changing parks, and cities like Seoul, South Korea, have taken old freeway overpasses and turned them into unexpected pedestrian corridors. When Shanghai’s former airport closed, it became a big blank slate ready for reinvention.

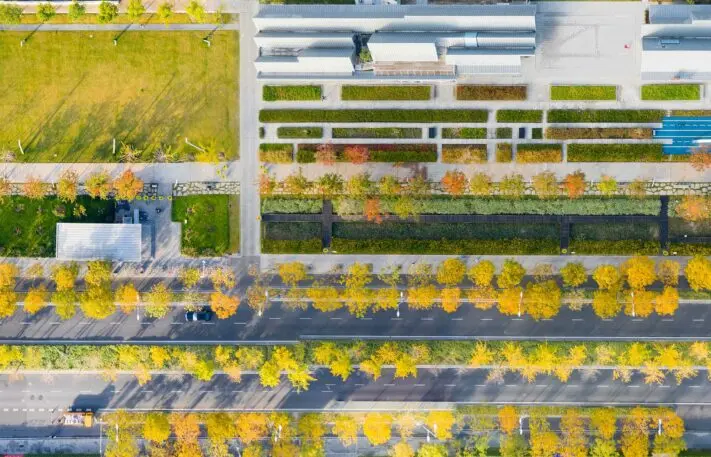

The park, like the runway before it, is long and linear, something Sasaki chose to celebrate rather than hide. Zhang says the site before construction was “relentless” in its size and straightness. “When we were structuring our park and the spatial design, we tried to emphasize that linear feeling,” she says. Walking paths cut straight down the 36-acre site, and a series of waterways, constructed wetlands, and rain gardens also form stripes through the space. The preserved width of runway and chunks of the original concrete that was torn up during construction make up walking routes from end to end.

The design breaks up the flatness by integrating subtle changes in topography, with sunken spaces that form garden areas and an entrance to a new subway line constructed beneath part of the site, as well as slightly angled walkways that are meant to evoke the takeoff and landing of a plane. Cafe buildings are scattered throughout the park, as are playgrounds and sports fields.

As urban regeneration continues in the surrounding district, the role of stormwater cleaning is likely to become even more important. High-rises and towers are now being built on both sides of the runway park, creating more residences, offices, and commercial uses in the area.

That’s also creating a built-in user base for the park itself. Since it opened late last year, the park has established itself as a valued public space. Playground equipment in some parts of the park has already had to be replaced due to overuse.

The park and the growing neighborhood around it are already interweaving. Compared to what it was like to stand on the closed runway before the park was built, Zhang says, the park has become more human-scaled. “A person felt very small,” she says. “But now a lot of buildings are up, the streets are up. The feeling is different.”

Recognize your company's culture of innovation by applying to this year's Best Workplaces for Innovators Awards before the extended deadline, April 12.