Sarah Wendell Sherrill is ticking off major art sales, including one that took place less than 24 hours before our phone chat. Flora Yukhnovich, an emerging abstract artist out of London, just sold her 2020 painting, I’ll Have What She’s Having, for $3 million at auction at Sotheby’s, 40 times more than its estimated sale.

The news has the art world chattering. And it has Sherrill—who started her career at Christie’s before cofounding the artists’ equity-management platform Lobus—shaking her head. The Yukhnovich sale, she explains, took place in a secondary market, meaning that Yukhnovich will see very little of that $3 million. (As a U.K. artist she receives a .25 percent royalty rate; contracts are different in some European countries.) As the art world currently exists—and always has—artists and galleries split a sale fee 50-50. But that’s just for the initial sale of the work. When the piece is resold at auction, or through private art dealers or collectors, the artist generally receives nothing.

In some cases, this means that an artist, or an artist’s estate, is missing out on millions of dollars. Consider the Basquiat piece that fetched $93 million at a Christie’s sale earlier this year. The painting originally sold for $4,000 back in 1984 (which translates to a little more than $10,000 today).

“Artists are still beholden to this model where they’re effectively making 30 cents on the dollar and no residual participation in the secondary market,” Sherrill says incredulously.

Now, four years after launching Lobus, which allows artists to self-manage their assets and essentially be their own bank—the platform manages $7 billion in assets for clients such as the Rothko family, Louis Vuitton Foundation, and Gagosian—Sherrill and cofounder Lori Hotz (also a Christie’s alum, along with investment banking firms) are doing their part to change this and, in effect, help artists connect even more directly to consumers.

How? Through nonfungible tokens (NFTs), which Sherrill declares are “the greatest unlock on ownership that art has seen in its history.” The idea is to use NFTs, which have been wildly popularized over the past year by the artist Beeple and NFT platforms like NBA Top Shot, to certify authentication of a physical work and build an artist’s ownership into that certificate. This means that every time the piece resells, the artist will receive a fraction of the sale—most likely from 5% to 20%. At any rate, it will be far larger than a fraction of 1%.

This model already exists on the blockchain with digital artwork, but it has yet to cross over to the traditional art world in a meaningful way.

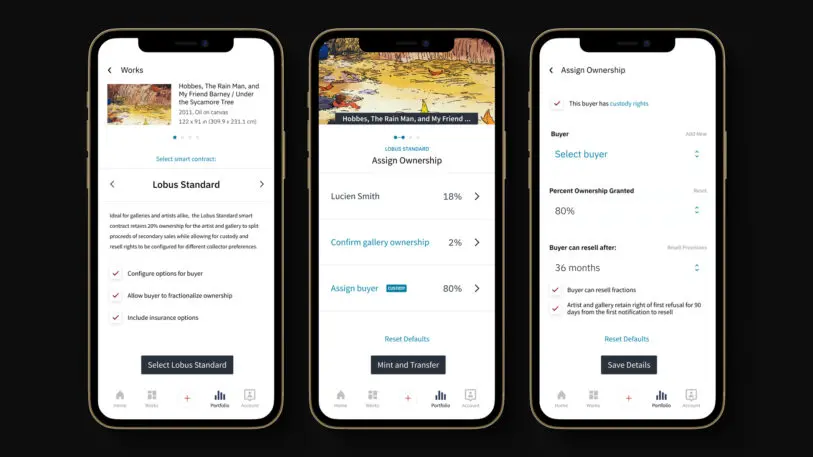

On Lobus, this will be possible through a new blockchain-based marketplace that the company is launching this week. There will also be new tools available to artists, such as smart contracts with equity and royalty capabilities. Lucien Smith, a New York-based multidisciplinary artist who has been working with Lobus on the technology, will oversee a new Cultural Innovation Lab that will seek out artists looking to use NFTs to build sustainable careers. The lab will help artists work within the new technology and offer educational programming in the form of events, webinars, and discussion groups.

“The goal of the lab is to incubate, create, and do R&D, and produce products for artists that put them in control of their business,” Sherrill says. “The artists we work with, whether they’re emerging or established, have a very specific track record. They have a market, they have a social media following. It’s really about, how does the business of the artists actually become something in the 21st century, in the same way you’ve seen it happen in sports and Hollywood and music.”

Sherrill adds that Troy Carter, an investor in Lobus and the cofounder and CEO of music-tech company Q&A, has been a “wildly important voice” in helping Lobus see how “the power structures of talent and creativity” in the art world “have been totally misaligned and inverted with where the money sat.”

Smith says, “We really have to think of an NFT as a new medium,” one that has a myriad of opportunities. For example, beyond using NFTs to establish ownership, artists can create accompanying NFTs to sell in conjunction with a physical work of art, in the same way that artists create lithographic prints based on a piece, allowing more people to enjoy the work at a lower price. Or NFTs could be made that complement the physical art or in some way create a dialogue with it.

“If I was making a painting, I could make an NFT that was just a digital image of the painting, or I could choose to take a facet of the painting and render it to be a 3D object and sell that,” Smith says.

This model offers “another portion of ownership” of the original painting, Sherrill explains. “You could sell those for $1,000 each. So suddenly an artist’s audience goes up from 1 collector to 101 or 10,001. The art world hasn’t had a mechanism to really open it up to that audience before.”

As for galleries, while they may be seeing their 50% revenue split trimmed down in this model, Sherrill argues that they have the potential to “build ownership alongside the artists. It’s not dissimilar from venture. I think we’ll see galleries look more like venture funds. A lot of them lose their artists as they go along in their career. But now they get to accrue value alongside them.”

Smith himself has experienced the pitfalls of being an artist in the traditional market. Some of his early works that he sold after graduating from the Cooper Union in 2011 sold for $20,000; 18 months later, they sold at auction for more than $400,000.

“Speculative art trading, it can do good and bad for an artist’s career,” he says. “But that type of trading oftentimes is beneficial to the collector—both collectors, the acquirer and the seller—with little regard to the artists. Adopting a blockchain and starting to attach artists’ ownership to what we know as royalty and resell rights, those sorts of things can create a healthier art market and still allow the types of traders, buyers, and collectors to operate in all that—but have the artists at the center of it.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.