At a sprawling Silicon Valley R&D facility, a neon sign on the wall says “transformation.” It’s not a metaphor: Inside large tanks within the structure, food waste is turning into the building blocks for compostable plastic.

“We’re using one huge problem—the carbon emissions from food waste—to solve another, which is the global plastics problem, and petroleum plastics as a whole,” says Dane Anderson, cofounder and co-CEO of Full Cycle Bioplastics, the San Jose, California-based startup that runs the facility.

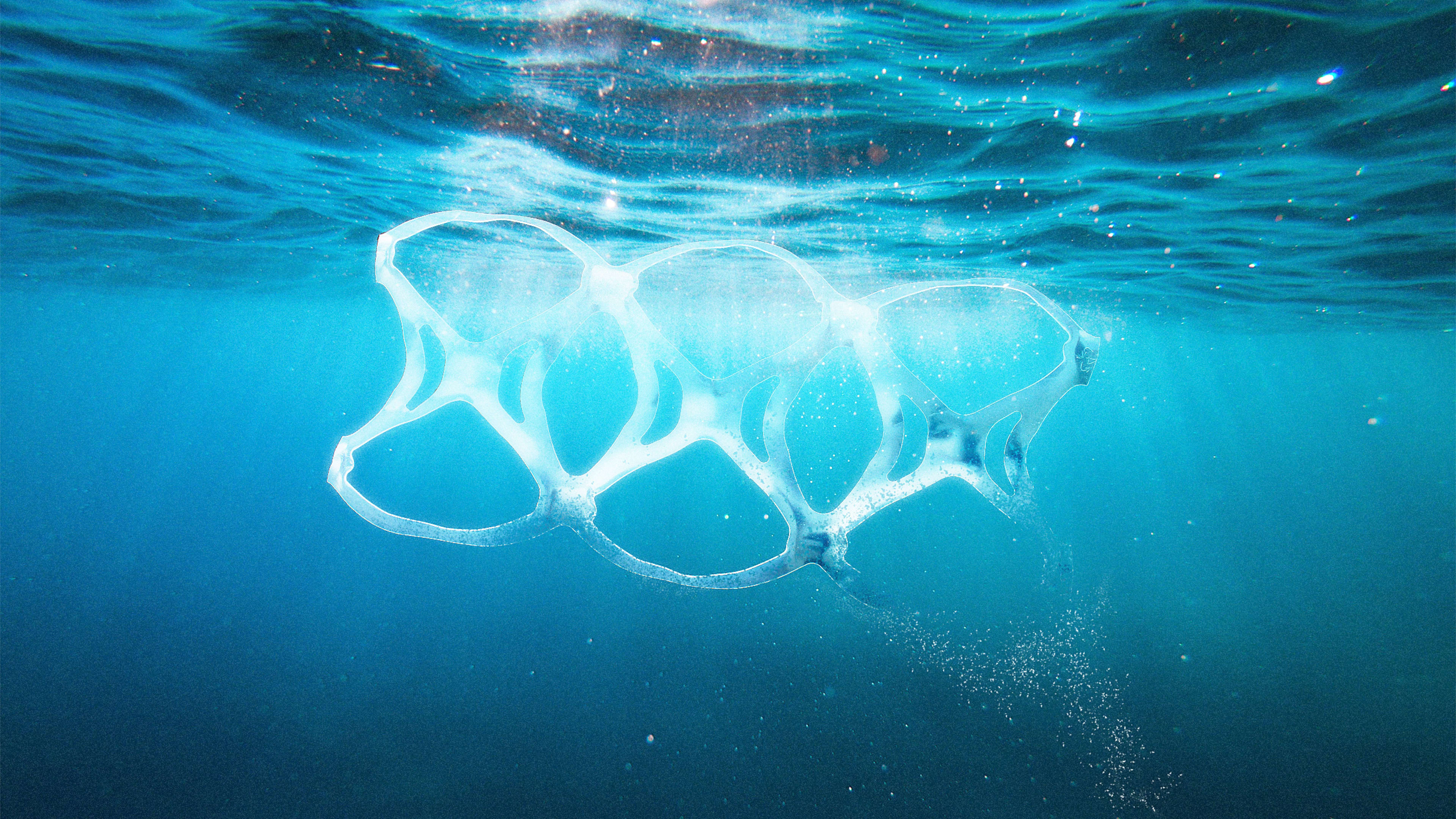

If PHA ends up in the ocean, it can break down in some conditions—if it’s near the surface in warm water, it can biodegrade in as quickly as seven weeks. If it sinks to the bottom, it could take years to break down. But unlike typical plastic, PHA isn’t likely to do any harm. It’s not toxic, and if a turtle or other animal eats it, bacteria in the animal’s stomach will consume it. “I’ve actually eaten some of our PHA,” Anderson says. “It’s a carbon source, just like any carbohydrate.”

Companies have been trying to make PHA for years, but there have been technical challenges along the way, and, arguably, the market also wasn’t ready for it in the past. A company called Metabolix built a PHA plant with Archer Daniels Midland in 2010, but it closed two years later because of a lack of sales. The situation is different now because consumers are well aware of the problem of plastic waste, especially from packaging. Most plastic packaging is thrown out rather than recycled, and a significant portion escapes into nature; there are now more than 150 million metric tons of plastic in the ocean. Big brands, pushed by consumer pressure, are making commitments to phase out virgin plastic in packaging.

“We’ve been at this for nine years, and it’s been a massive shift over the course of that time,” Anderson says. “I think brands are absolutely ready, and putting their money where their mouth is on trying to create the opportunities for better materials.”

Full Cycle is unique in that it makes PHA out of food waste. (Another company making PHA, Bainbridge, Georgia-based Danimer Scientific, uses canola and soy instead.) Full Cycle can also make virgin-quality bioplastic out of its own material, so, like the name suggests, it can actually operate in a completely circular system; if the company receives a bunch of its own PHA packaging back, for example, it can put that material through its process again. Because food waste is a low-cost feedstock, the plastic can be competitive with fossil-based plastics, the company says. And because food waste in a landfill emits methane, a potent greenhouse gas, the process can help eliminate those emissions and shrink the carbon footprint of the final product.

The company plans to co-locate its technology at composting plants, creating a new revenue stream for composting companies. After years of R&D, including a stint at a U.S. Agriculture Department “bioproducts” lab, the company is now preparing to build its first commercial-scale facilities, beginning with one based in New Zealand.

“We’re scaling rapidly, and commercializing rapidly, because plastics is such a huge market,” Anderson says. “There’s so much demand for this that to make the impact that we’re out to make, we have to go fast.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.