Many companies are reacting to the climate crisis by hastily formulating long-term plans to go carbon neutral. Not Google. That’s because it accomplished the goal way back in 2007, by purchasing enough carbon offsets to compensate for the greenhouse gas emissions it produced. The company eventually racked up enough offsets to zero out all the emissions generated since its founding in 1998. And by 2030, it aims to run all of its data centers worldwide 24/7 on 100% clean energy—no offsetting required.

Enormous though Google is—and as much progress as it’s made on the sustainability front—it’s just one company. That helps explain why it’s also taking on a less inward-looking challenge with plenty of potential: Supporting other companies as they undertake their own ambitious efforts to reduce their carbon impact.

Today, at its virtual Next conference, Google’s cloud-computing arm, Google Cloud, is rolling out tools for measuring and reporting the carbon emissions relating to its customers’ use of its cloud services. It’s also introducing a preview of the first version of the Google Earth Engine satellite imagery/geospatial data platform designed for business use.

According to Sundar Pichai, the CEO of Google and its parent company Alphabet, these new features aren’t just about Google trying to nudge its customers in a responsible direction. Instead, companies are already committed to doing so and are eager for assistance from their partners. “Every CEO I talk to is focused on sustainability,” he says. “And so using Google Cloud to help them make that transition is a real innovation opportunity.”

Moreover, today’s innovations might be tomorrow’s table stakes. “Five years ago or 10 years ago, cybersecurity was not a board-level topic,” says Thomas Kurian, Google Cloud’s CEO. “And today, it’s become part of the risk and audit process of any organization. As climate changes, we expect that climate risk—the impact of that on a company—will become more and more of a board-level topic.”

Anticipating what customers want is key to how Kurian sees his job. An Oracle veteran who succeeded VMware cofounder Diane Greene as Google Cloud CEO in January 2019, he’s been charged with shaking things up at the organization, which has long trailed Amazon Web Services and Microsoft Azure in market share. Part of that shakeup, he says, has been acknowledging that Google’s classic self-image of itself as “the best place for people who want to build great technology” is not itself enough for Google Cloud to flourish.

“That cultural tenet we all share in our cloud organization—our success comes from our customer’s success—has been one of the big changes we’ve had to make,” he says. “And we’ve been thrilled with our progress.” Increasingly, a meaningful chunk of that success may come from Google Cloud’s ability to help companies succeed at sustainability.

‘We’re able to provide pretty granular information’

When it comes to reducing the carbon toll of computing, Google “does deserve a lot of credit for pushing the market, because they’ve been doing it for a very long time and they are being transparent about it,” says David Mytton, a London-based entrepreneur who writes about the cloud and sustainability. “They’re not claiming that everything is great and 100% renewable right now. They’re saying, ‘this is where we’re at, this is where we’re going to get to.'” (Mytton also credits Microsoft for Azure’s carbon-reduction efforts but says that AWS has been the least forthcoming of the big three.)

Given Google Cloud’s ultimate goal of ridding carbon emissions from its data centers altogether, the day may come when its customers don’t have to devote much energy to understanding the impact of their own Google Cloud usage. In the meantime, decisions must be made. “For the next 10 years, as we work to achieve that, we’re providing new tools to our customers to choose low-carbon options amongst our infrastructure,” says cloud sustainability lead Chris Talbott.

With that in mind, Google Cloud recently updated its tool that helps customers select regional data centers by adding icons that call out the options with the lowest carbon impact. The company says that when these icons are available, customers are 50% more likely to opt for a clean choice; Talbott likens it to the positive effect of Google Maps factoring greenness into its routing recommendations.

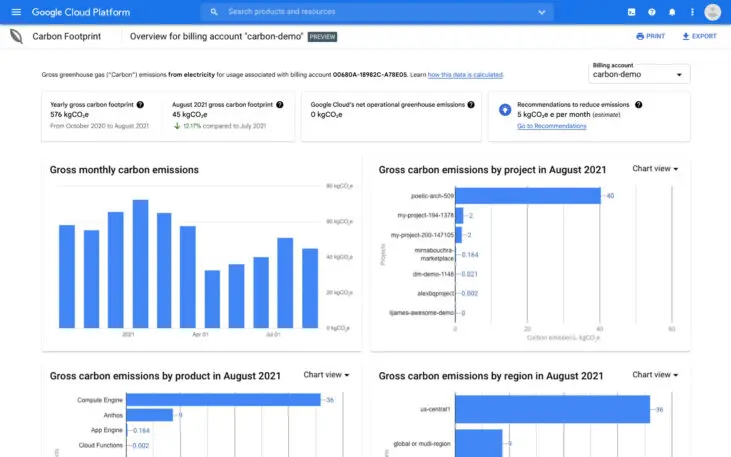

Now the company is deploying Carbon Footprint, a much richer set of tools for informing customers about the environmental implications of their use of Google Cloud Platform services. As you might expect, the new features—in the same zip code, at least, as Microsoft Azure’s Sustainability Calculator, introduced last year—leverage data that Google has been monitoring for internal purposes for a long time. “We are constantly optimizing our own energy footprint,” says Kurian. “But customers want to see their usage through a different lens. So we built some custom tools for them.”

“Because we have granular metering across all of our underlying infrastructure—the data centers, the machines, the networking that ultimately Google cloud services run on top of—we’re able to provide pretty granular information at the product level, the project level, the location,” says Talbott. “So global customers will be able to see where their emissions are concentrated across the globe.” Data for each month will be available within 21 days—a speedy turnaround time by the standards of such reporting.

This precision and timeliness are critical to global bank HSBC, one of the Google Cloud customers that’s been piloting the Carbon Footprint features. The company already had a handle on its overall emissions, but “what we can now do through this tool is see what is happening within our applications within specific types of code or particular toolsets that we are using within our applications on the cloud,” says Stephen Bayly, the bank’s CIO for markets and securities services. “It’s that granularity that enables better decision-making.”

Along with introducing Carbon Footprint, Google Cloud is giving a sustainability-minded upgrade to an existing tool called the Unattended Project Recommender. Already, it uses machine learning to find code running on Google servers that a customer may simply have forgotten about. “We can identify with high confidence that [a task] may be idle or abandoned,” says Talbott. “Perhaps someone has left the organization, or this isn’t a project in use anymore.”

Now the Unattended Project Recommender will also estimate the gross carbon emissions that would be eliminated if a customer did away with such phantom jobs. They add up: In August, Google Cloud calculated the aggregate monthly figure for all of its users and found that it amounted to 600,000 kilograms Co2 equivalent—the same as a car driving 1.5 million miles.

‘How can Google help us?’

Another new Google Cloud tool being announced today could have sprawling impact far beyond the walls of Google’s data centers. Google Earth Engine provides rich capabilities for analyzing the satellite and geospatial data that are critical to sustainability initiatives of many kinds.

Though Google Earth Engine is new to Google Cloud, its history dates to 2009. The service “was essentially born in the Brazilian Amazon,” explains Google Earth director Rebecca Moore. “We were down there doing training on Google Earth, and we were approached by geospatial scientists in Brazil who said that we were losing a million acres a year of the Amazon rainforest to tropical deforestation. Much of it was happening in remote parts of the forest that were not supported by law enforcement on the ground.”

Satellite imagery could play a significant role in helping curtail such harm to the environment. Historically, however, it had been salted away in government archives. It also required a vast amount of computing power and storage space to analyze. Google had both the imagery—which it had been collecting for Google Earth—and the technological wherewithal to process it. And so the company gave scientists, academics, and non-governmental agencies access to petabytes of data that they could crunch using their own algorithms. Twelve years later, over 50,000 active users call on Google Earth Engine to do everything from observing tiger habitats to predicting malaria outbreaks.

For most of Earth Engine’s history, Google actively resisted turning it into a product aimed at businesses. It offered the service for free but granted access only after prospective users explained what purpose they had in mind. Use for “sustained commercial purposes” was explicitly banned.

Conversations with massive companies whose carbon footprints involve global supply chains got Google reconsidering that stance. “We started seeing a lot of this coming from enterprises like Unilever and [Procter and Gamble] and all of these large corporations,” says Google Cloud senior director of product management Sudhir Hasbe. “They were like, ‘hey, we have to focus on sustainability. How can Google help us?'”

A visualization of surface water change in the Aral Sea from 1984 to 2020, generated using Google Earth Engine imagery.

Among possible answers to that question, Google Earth Engine quickly rose to the top. “There’s just been a transformation in societal awareness of these issues and the corporate and governmental commitment to address them,” says Moore. “And so it seemed like this was really the moment to put this kind of Large Hadron Collider-type instrument into the hands of these kinds of organizations.”

For Unilever—the huge producer of consumer packaged goods ranging from Dove soap to Axe deodorant and Knorr soup to Ben & Jerry’s ice cream—no sustainability initiative matters more than its effort to change its relationship with palm oil. The company buys the stuff in vast quantities to use in many of its products. But production of palm oil, which has been called “the world’s most hated crop,” is a major cause of deforestation in Southeast Asia. Hence Unilever’s goal of making its supply chain deforestation-free by 2023.

This aim is complicated by the tangled process by which the company gets its palm oil, which it procures from 1,900 palm oil mills that work with small farmers. Often, “the supplier of the supplier of the supplier is where the issue is,” says chief supply chain officer Marc Engel.

As one of Google Earth Engine’s first corporate testers, Unilever has woven the platform into its effort to understand where its palm oil is coming from, which also involves tracking its supply via mobile phone geolocation and working with Aidenvironment and Earthqualizer, two nonprofit consultancies. “It’s completely game-changing, because a player like us, who sits at the end of the chain using those products and derivative products all over the world, is all of a sudden able to get access to this data,” says Engel. He’s already investigating how Unilever might apply Earth Engine to its supply chain for other raw ingredients, such as cocoa and tea.

Earth Engine’s debut as a Google Cloud Platform product could be a game-changer for Google, too. The more that Google Cloud can leverage ambitious, Google-y offerings created elsewhere in the company, the better its chances of winning business in ways that AWS and Microsoft Azure can’t easily match.

With Google Cloud Platform, “we are really focused on bringing the best of Google in ways that help the customer, and Google Earth Engine is a great example of it,” says Pichai.

‘A hard but necessary slog’

If big companies trust Google as a sustainability partner, it will be in part because it’s figured out how to earn their trust, period. Google entered the cloud computing business in 2008 with a service called Google App Engine. But for all its expertise at deploying advanced technology at scale, it had a lot of learning to do. By creating AWS, Amazon had already jumpstarted the cloud-services category and gained a formidable head start. Azure benefited from Microsoft’s decades of experience as a technology provider to companies of all sizes. Google—which had prospered by building products that consumers loved and monetizing them through advertising—had no such built-in advantages.

And for years, it struggled with a perception that it wasn’t serious enough about the needs of enterprise customers. Kurian rattles off stats to argue that this has changed. “If you look at the 10 largest companies in the world in retail, in media, in software and services, we work with eight of the 10,” he says. “In manufacturing, we work with seven of the 10. In capital markets, we work with seven of the 10. These are not just digital-native companies that were born in the cloud, of which we have many, but also more traditional companies that normally would have been anxious about working with a new technology provider.”

Kurian has bolstered Google Cloud’s ability to serve specific business sectors through hires such as former SAP executive Lori Mitchell-Keller, who joined in May 2020 as VP of industry solutions. She says that the organization has gotten good at “developing the strategy and the narrative about how we’re going to attack [an] industry. And that goes all the way from the strategy documents down to what actual solutions we are going to build. Our organization works very closely with both the infrastructure teams and the AI/[machine learning] and engineering teams to say: ‘These are the things that are the biggest business problems, and these are the solutions that we need to solve them.'”

Market-share figures for the three behemoths of cloud computing show that Google Cloud Platform remains an underdog. In the second quarter of 2021, according to research firm Canalys, it had 8% of the market, well behind AWS with 31% and Microsoft Azure with 22%. Still, by several measures, it’s picking up steam. Canalys says that Google Cloud Platform grew by 66% in the second quarter, besting AWS and Azure’s growth rates. In Google’s most recent quarter, Google Cloud revenue reached $4.63 billion, up 54% over the previous year. It reported an operating loss of $591 million, but that was down from $1.43 billion a year earlier.

The uncommon patience Google has shown with Google Cloud over the years might have felt like a necessity rather than a choice. “If Google cedes this market to AWS and Microsoft, winning back the hearts and minds of developers for future endeavors will be impossible,” says Raj Bala, a VP at research firm Gartner. “So yes, it’s a hard but necessary slog.” He adds that “Thomas Kurian has had an absolutely positive impact on Google Cloud Platform and the outfit’s competitive stance.”

One person whose opinion matters quite a lot professes satisfaction with Google Cloud’s progress and prospects. “Obviously, it’s a market that’s growing rapidly, and Thomas has positioned us very well for long-term growth,” says Alphabet/Google CEO Pichai. “And he has such a clear vision for where the market is headed.”

Kurian may credit Google Cloud’s recent momentum to organization-wide “enterprise focus and customer empathy,” but it’s no surprise that Pichai comes back to a loftier topic never far from Google’s mind: technical innovation as a form of human progress. “We are investing deep in foundational technology, be it AI, be it data analytics, be it quantum computing, be it security,” he says. “Bringing all of that to companies around the world is a deep part of how we can achieve impact in the world. And so we have taken a very long-term view.”

As Google Cloud continues to play catch-up with its larger rivals, more patience will be required—along with success at convincing prospective customers that the commitment is real.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.