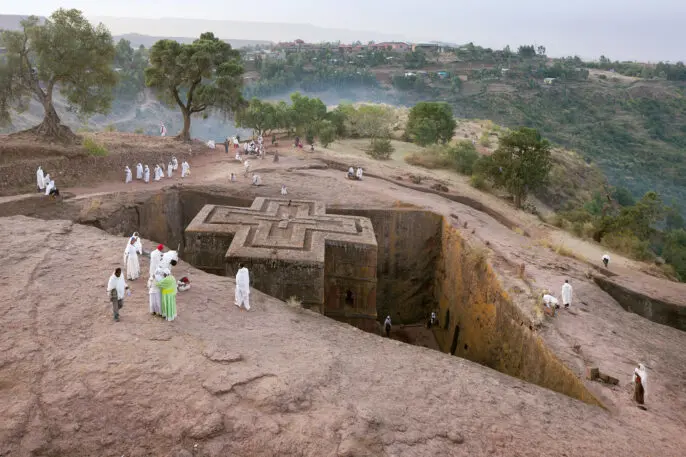

For millennia humankind has dug downward for shelter, security, and comfort. Born out of pure necessity, using nothing but the ever-present earth, humankind created architecture by subtraction. In Ethiopia, monolithic churches were hewn out of rich volcanic rock. In India, elaborate temples were carved from cliffs. And in China’s Loess Valley, underground dwellings were constructed within the porous ground.

Within much of this earthen vernacular, habitation is described by what is removed. The ground is sculpted into poché and manipulated to define interior space. Taking away, often by hand, only what is essential, humankind exists within niches of the earth’s crust. The structural limit of the material, the nature of the tools, and the intended purpose of the space define this subtractive construction.

Subterranean spaces are easily isolated and insulated from the fickleness and volatility above, making them the preferred spot in an apocalypse. Both China and Russia constructed vast underground cities during the Cold War in anticipation of nuclear fallout. Likewise, the subterranean Željava Air Base in former Yugoslavia was designed to withstand a nuclear bomb equivalent to the one that devastated Nagasaki.

On a lighter note, depth and isolation also make subterranean space an opportune place for observation. One thousand meters below ground, the Super-Kamiokande detector has been built in anticipation of the next supernova. Here, deep within the earth, we investigate the creation of matter in the universe above.

An immense demand for space has pushed the mechanics of our lives underground. Over the last 200 years, virtually every urban lifeline, 90% of our transport infrastructure, and a colossal number of cables, pipes, wires, and tunnels have been buried. In their midst, buildings have grown downward, digging out more and more space to support structure, services, and the pesky car. This space beneath our feet has become essential. A subterranean city grows beneath the city above, an ingenious space-saving solution for our ever-expanding cities. In Kansas City, 10% of the total commercial real estate is underground. Since 1964, space has been carved from a 270-million-year-old limestone deposit to create SubTropolis, the world’s largest underground business complex.

The regulating temperature of the earth also makes it an opportune place in which to bury our (liquid) treasures. In recent times, the subterranean wine cellar has become the subterranean winery. The surge in this underground typology is noticeable, culminating in the extraordinary Antinori Winery by Archea Associati, near Florence. Here the client, the 27th generation of the Marquis family, made the difference. Their profound commitment to this typology meant that any delay or extra costs associated with what seemed at first a simple project was absorbed and accepted.

Sadly, this fascination for subterranean space is not evenly spread. Until recently, an estimated 40 million Chinese people lived in the Yaodong. But much of this is being swept away by modernization. Adobe structures in the Dadès Valley in Morocco are meeting a similar fate. Globally, this earthen vernacular is being eroded at an incredible pace, only to be replaced by ubiquitous concrete units.

The tourism industry is doing its bit to resuscitate these habitats. The Yaodongs in China and the Sassi di Matera in Italy are being transformed into hotels for those who wish to get back to basics with a smattering of luxury. The jury is still out on whether this represents a preservation or perversion of these underground structures, but the tourist looks like a necessary evil in combating the shrinking biodiversity of our habitats.

Not all underground developments are successful. In our research we have seen that digging down carries the same risk as stretching upward. A desire for greater control often breeds isolation, alienation, and disconnection.

The success (or failure) of these underground structures can be found in the degree of enclosure and how they manage often-competing interests of enclosure, light, depth, and orientation. Those that are successful blur the line between building and ground. They shift their expression from plan to section to confront and design the connection between the context above and space below. This moment of exchange within the crust of the earth is where their intelligence lies.

This essay was excerpted with permission from Dig it! Building Bound to the Ground by Bjarne Mastenbroek and Iwan Baan (Taschen, 2021).

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.