We will eventually stop burning fossil fuels. The question isn’t if oil and gas fades from the picture, but whether it can happen quickly enough to stave off environmental catastrophe. Here in Louisiana, with our enormous investment in oil pipelines and tank farms fed from oil platforms in the Gulf, this is an issue of more than passing concern. It’s time now to begin thinking about how we can repurpose these potentially enormous assets.

Last month, the UN issued its dire report on climate change—Secretary General António Guterres declared the crisis a “code red for humanity.” As if to underscore the urgency of that message, Western towns and forests were consumed in drought and raging wildfires, while in the Southeast and then the Northeast, Hurricane Ida swamped the Middle Atlantic with unprecedented rainfall and flash floods.

We’re living in a world of water imbalances, but it’s one that could be righted by reusing existing infrastructure in radical new ways. This is not magical thinking. The shift to renewables is now underway worldwide. The cost of solar and wind power continues to drop, as investors pull out of oil and gas. (Even Norway’s trillion-dollar wealth fund, created from the proceeds of oil exploration and extraction, recently sold the last of its investments in fossil fuels.) The squeeze on the industry—from governments mandating electric cars to a possible carbon tax—will continue. At some point even Big Oil will succumb to the laws of economic gravity (or find new business models).

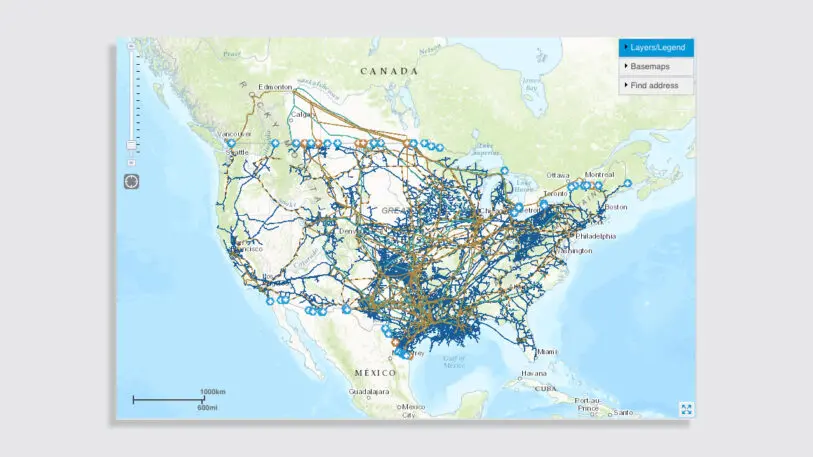

We know that extreme weather conditions will escalate in the coming years. Severe drought across the Southwest and Western regions of the United States is likely to persist and intensify. But a solution lies just underground, not in the parched aquifers, but in the pipes that have for decades channeled the fossil fuels now certifiably complicit in driving us to the brink. A staggering 2.3 million miles of oil and gas pipelines crisscross the United States, most of them with paths that end or originate in two states, Texas and Louisiana.

We are a current and a former resident of Louisiana, an oil-dependent state that has been beholden to fossil fuel companies for a century and paid a steep price for it. The Pelican State is famously rich in other ways: music, food, culture, wildlife. But our greatest resource in the foreseeable future may be our access to fresh water. In fact we spend hundreds of millions of dollars a year keeping excess water (some of it potentially potable) from inundating us. Given the water shortages in the rest of the country, this seems like a very broken paradigm.

The existing oil and gas pipelines connect the rest of the continent to the Gulf of Mexico—a source of water that would have to be desalinated, at grave environmental cost. (Right now much of that infrastructure, post-Ida, lies in ruins, creating a huge toxic soup.) Louisiana is also washed by the outfall of the mighty Mississippi River, one of the nation’s largest sources of fresh water. Add to that annual rainfall of more than 60 inches, with considerably more projected in the future. The state is in fact on track to set a record for rainfall this year (a mark that’s unlikely to go unbroken for long). We’re swimming in excess water, rich in potentially potable water. So why not repurpose the system of pipes currently distributing fossil fuels, and use it to distribute the fresh water needed to sustain life elsewhere in the country? What if oil storage tanks were converted into rainwater reservoirs and capturing it became an industry? What if Louisiana transitioned from oil-production (a dying industry, linked to high rates of cancer) to water distribution (linked to life itself)? What if the Great Lakes were also hooked up to this transformational water-delivery system?

Well before the value of water reaches parity with the value of a barrel of oil, incentives exist to begin converting our existing oil and gas infrastructure. We don’t have time for the federal government to design, plan, and approve a national water pipeline, as some have proposed. Our recent track record with these large projects, when a decade is considered fast, remains spotty at best. Do we really think a national pipeline, authorized by Congress and built by the Army Corps of Engineers, could be completed in 10 years, let alone in time to keep California, Arizona, Nevada, and New Mexico from running out of water? Utilizing existing infrastructure is the only approach that meets the urgency of the moment. For those worried about using water drawn from former oil conveyances, fear not—pipelines are routinely reversed and repurposed for new uses.

Even if the water distributed through the oil pipelines wasn’t immediately drinkable, that almost infinite volume of new water could be used as greywater, which still constitutes a very healthy percentage of total water use. In addition, the science required to make all of this transported water potable is surely shorter in timeframe and exponentially cheaper in cost than building an entirely new distribution system.

We’re long past the time when we can “mitigate” our way back from the abyss with incremental measures. The impacts of our climate emergency are here; they’re immediate, and they’re pressing upon us. Responding to them will require boldness, creativity, and a willingness to find unconventional solutions to seemingly intractable problems. Repurposing our oil and gas infrastructure, that vast tangle of pipes, is just such an opportunity—an elegant solution to an increasingly wicked problem.

Recognize your company's culture of innovation by applying to this year's Best Workplaces for Innovators Awards before the extended deadline, April 12.