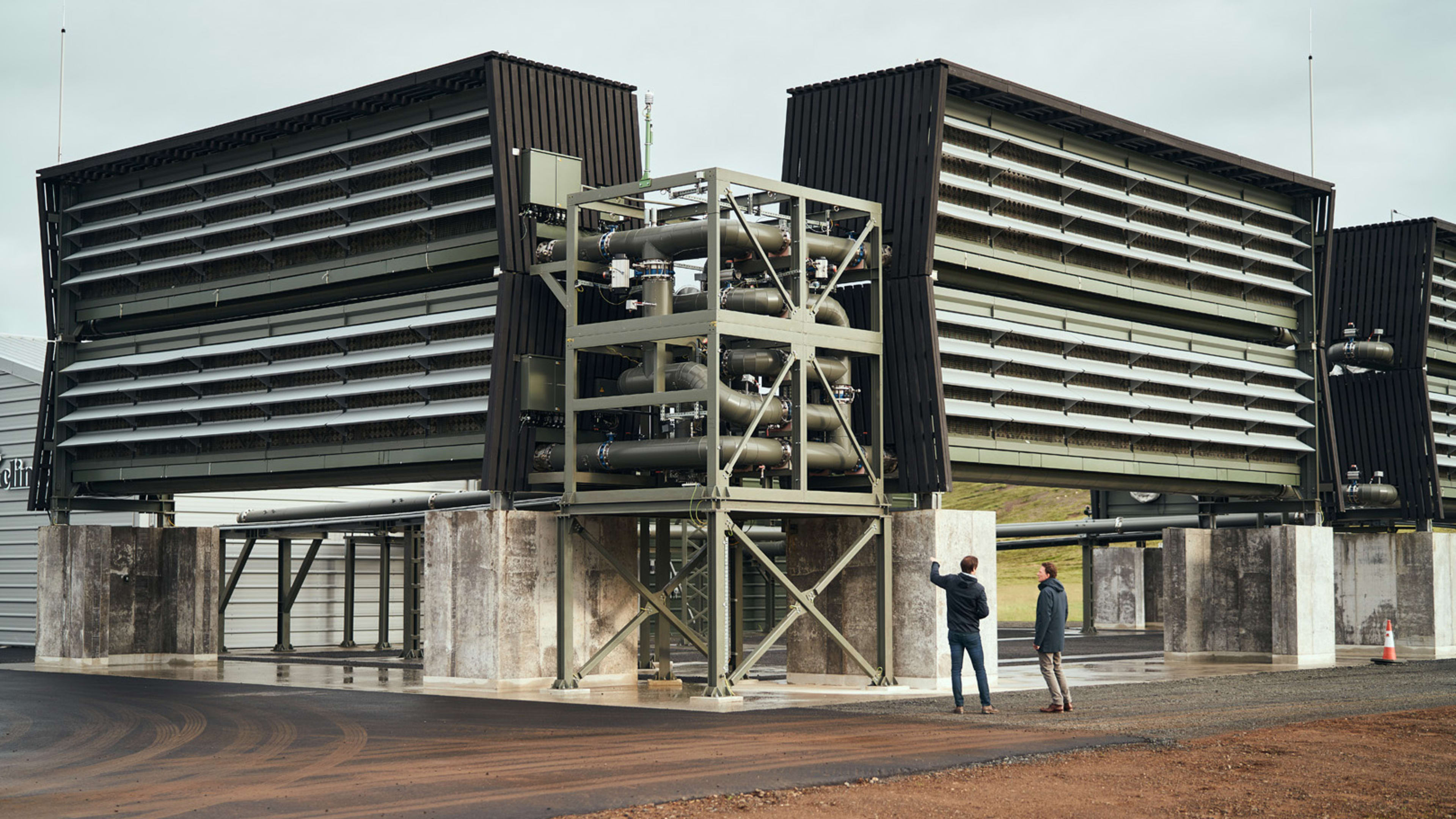

In a field surrounded by barren hills in a remote corner of southeast Iceland, eight new shipping container-sized boxes sit arranged in a U-shape. Each is filled with fans that pull the outside air into a filter that chemically captures carbon dioxide; the devices then extract the CO2 so it can be pumped underground and permanently turned into stone. Welcome to the world’s first commercial carbon removal factory.

“Every ton which is captured from this plant is one that is immediately not contributing to global warming,” says Julie Gosalvez, chief marketing officer at Climeworks, the company that built the new plant, called Orca, which is an expansion of a pilot plant at the same location.

“I think this is a big milestone for a few reasons,” says Noah Deich, president of the nonprofit Carbon180, which studies and advocates for carbon removal. “The first is that I think from the climate front, it’s become increasingly clear that we can’t just stop emissions, and that we also have to think about cleaning up the legacy CO2 that remains in the air from the past. And that means taking CO2 in the atmosphere, putting it back in the ground, and doing so in a way that’s pretty permanent. The fact that Climeworks is doing this now, at a commercial scale, is really important to show the world that the time for thinking about legacy emissions is not at some distant future, when we’ve already stopped, but to do it in parallel and to start now.”

Capturing carbon directly from the air isn’t cheap. Climeworks hasn’t shared the expected cost of running the Orca plant, and says that it needs concrete data from operations first. In 2019, executives said that costs were between $500 and $600 per ton of carbon at the time. Part of the challenge is the amount of energy used. (Iceland is a good place to start both because it has ample renewable energy, so running the plant doesn’t have a large carbon footprint itself, and because that energy is cheap.) Reforestation, as a point of comparison, can cost around $50 per ton of CO2 captured, though it also runs the risk that the sequestered carbon may be lost in a forest fire. Forests also need much more land than the artificial carbon collectors, and a newly-planted tree can take a decade before it starts sequestering carbon at its maximum rate.

Companies like Microsoft and SwissRe, which have become early customers of Climeworks’ carbon removal service, hope to help the startup grow so that costs can come down. To make a difference, it will have to grow exponentially: The current Orca plant can capture 4,000 tons of CO2 a year, but the world may need to capture 10 billion tons of CO2 a year by the middle of the century, by one estimate, to have a chance of limiting global warming to 1.5 Celsius and avoiding some of the worst impacts from climate change. (That’s on top, of course, of an equally massive global shift to eliminate emissions from things like power plants and cars.) Another report estimates that by the end of this decade, we may need to capture 1 billion tons of CO2 a year. Other carbon capture plants will also come online soon from other companies, including two plants now in planning from the startup Carbon Engineering, which can each capture as much as a million tons a year, though that’s still only a tiny fraction of what’s needed.

“What we’re talking about with this commercial project is really like some of the very early solar power projects or wind power products 20 or 30 years ago,” says Deich. “And we’ve seen how quickly those industries can grow and reduce costs. But emissions continue to rise. So it’s one of those things where it’s going to take decades, even if we do it at breakneck speed, to get to the place that starts to matter for climate. And so the fact that we’re starting today is really, really significant.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.