In July 2019, my coauthor Hana was hit head on by a passenger truck attempting to pass in a no-passing zone. The whole family was seriously injured, but most of all the female passengers, whose spines were fractured and intestines torn. Halfway across the world and five months later to the day, a distracted driver jumped lanes and smashed into me. In that crash too, I and the other women in the car suffered a ruptured intestine and broken bones, while the men walked away mostly unharmed. By the time Hana and I found each other a year later, united by a search for answers, more than 400,000 women had been severely injured by motor vehicles.

What we didn’t know at the time was that our shared trauma was not unique—the sisterhood of vehicle-crash victims is farther reaching than we realized. Mothers and daughters are bonded not by stories and laughs, but by traumatic brain injuries, permanent scars, and moments of horror sealed into memory.

In 2019, 10,420 women died from motor vehicle crashes, and over 1 million sustained injuries. While men are more likely to cause crashes, women are more likely to die in them. None of this is surprising to car manufacturers or the government agency responsible for car safety standards, both of which have known these statistics for decades. While bias plagues many of our nation’s institutions, perhaps none are as shocking as a government- and industry-sanctioned practice that protects men and kills or seriously injures the other 50% of the population. The government’s long-acknowledged negligence bears the responsibility, while women and their families carry the consequences.

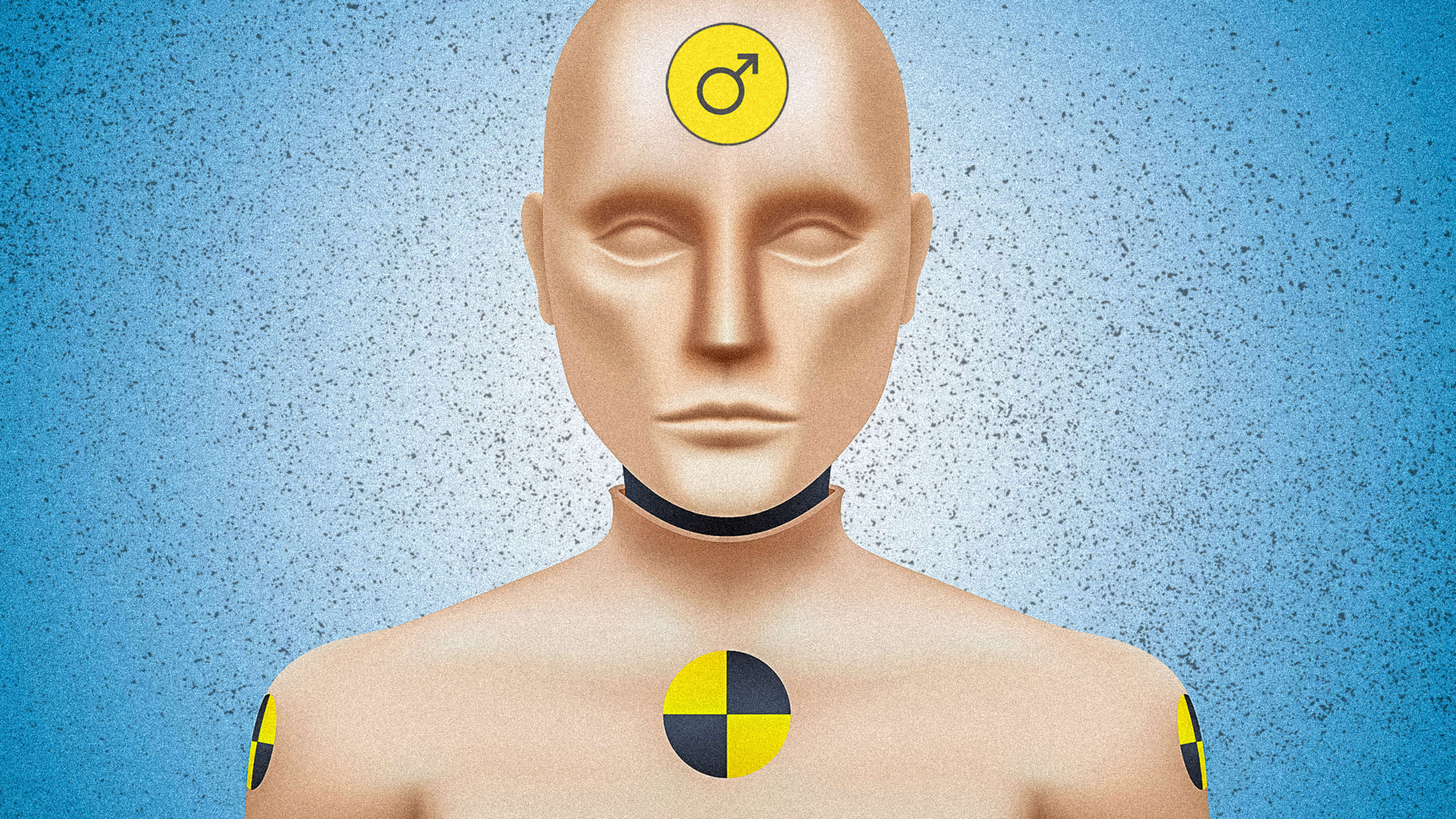

Every car that receives a safety rating from the National Highway Safety Transportation Association (NHSTA)—the nation’s safety rating agency—undergoes four tests. Intended to mimic the impact of frontal, rollover, side, and side pole crashes, these tests represent the standard to which automakers design their cars. Even though women are 72% more likely to be injured, and 17% more likely to die in a car crash than men, the frontal crash test the agency requires is only performed using a male driver. There is no mandated test that simulates a female driver.

For tests with women in the passenger seat, the dummy used to represent women is merely a scaled down male—4’11”, 108 pounds, and lacking any sort of internal morphology that distinguishes between sexes. Unaccounted for are the varying bone densities, muscle structures, and abdominal and chest physiologies that differentiate women from a male dummy. For example, the neck musculature of an average woman contains far less column strength and muscle mass than a man’s, making women 22.1% more likely to suffer a head injury than men. The current standards are designed to prevent men’s heads from smashing into the dashboard and do that quite effectively, reducing 70% of whiplash in men. For women, however, the seatbelts and airbags that protect men can actually cause additional injury. Both of us have permanent scars from the seatbelts we were raised to believe would save our lives, but which also nearly ended them.

Regulators have known for over 40 years that the internal structures of women put them at greater risk than men. In 1980, based on the recommendation of a team of researchers at the University of Michigan, NHSTA prepared to create a family of dummies that would have included a true female representation. When the Reagan administration came into power in 1981, the agency’s budget was slashed along with many other cuts to the federal government—the accurate female dummy was a casualty of those cuts.

Industry data shows that part of the reason women are at greater risk than men is that we tend to drive smaller, lighter vehicles, while men gravitate toward bigger cars and trucks. The industry knows that heavy passenger trucks put women at tremendous risk—a 1988 Oxford University study found conclusively that the “principal determinant of death is the weight of the vehicle concerned.” Heavy vehicles are also a greater threat to pedestrians than small cars—and pedestrians are more likely to be women or people of color. But the motor vehicle industry, untethered by government regulations, keeps building bigger and more lethal cars, putting more female lives at risk for the sake of men’s enjoyment and their own profit. The Ford F-Series truck is currently the best selling vehicle in the nation, clocking in at 5,605 pounds.

Even worse, the automobile industry is only one example of how women are often erased from critical design decisions. As Caroline Criado Perez notes in the book Invisible Women, countless products from smartphones to stoves are developed without women in mind. Often, this is a failure of omission rather than a purposeful exclusion. The people sitting around the table in most transportation, engineering, and automotive conversations are men. Unless someone happens to ask about women, we are simply treated as an afterthought. This failure affects women’s lives on a similarly grand scale: It makes us poorer, sicker, and, when it comes to cars, is killing us.

Now, there may be hope. Embedded in the House of Representatives INVEST in America Act is a provision requiring updated and more equitable dummy implementation tested in every seat. Bringing the New Car Assessment Program into this century is certainly an admirable goal, and one that other countries have long ago accomplished.

The NCAPs of Europe, Japan, and China were originally modeled after America’s. They, however, have not been handicapped by persistent negligence, opting instead into using more sensitive dummies rather than offering inflated five stars to everyone. Although national pride, innovation, and the desire to be a more equitable society may be enough motivation yet, the inability of American-made cars to meet international safety standards may ultimately render them unsellable on the overseas market.

Unlike the House’s infrastructure legislation, the Senate’s recently passed version lacks the specific language necessary to ensure that the NHSTA prioritizes safety for all. But NHSTA and the Department of Transportation shouldn’t have to need a push from Congress to protect half the population.

Although glaring inequities in our society abound, rarely are they so directly fatal, and swiftly solvable. If the Senate chooses to leave women out of the infrastructure bill, they will build new roads on a bloody foundation.

This is the moment to make this historic and needed change in vehicle safety. With a president who himself knows the pain of losing female loved ones to a car crash, and our nation’s first female vice president, who herself is at greater risk every day she buckles into a car, if not now, when? We will no longer be ignored, left out, and endangered. It is time for our government to stand up for the most vulnerable.

Maria Kuhn is studying political science and psychology at Columbia University. Since recovering from a head-on car accident in December 2019, Kuhn has authored articles and lobbied government officials to make cars safer for girls and women. Hana Schank is co-director of the public interest technology program at New America.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.