On an afternoon in late July, as a heat wave hit the Pacific Northwest, a 69-year-old farmworker named Florencio Gueta Vargas collapsed in the farm field where he was working in Washington’s Yakima Valley. When he didn’t return home that night, his family came looking for him at the farm. They were told that he was at the morgue.

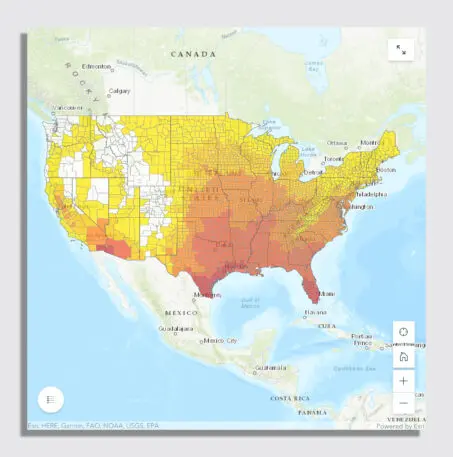

It’s the type of tragedy that will become more common as climate change boosts extreme heat. A new study maps out where outdoor workers will be most at risk from heat by the middle of the century. “We wanted to look at outdoor workers because they’re among the people who are most exposed to extreme heat in our country,” says Kristina Dahl, a senior climate scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists and author of the report. “And our earlier work had shown that if we fail to reduce our heat-trapping emissions, there would be a steep rise in the frequency of extreme heat over the next 30 or 40 years.”

Some jobs can also temporarily switch workers to less intensive work, but that isn’t always possible. While robots can potentially handle some jobs, like harvesting fruit on swelteringly hot days, that doesn’t address the problem of how to make up lost income. “The solution isn’t necessarily to get rid of these jobs that people rely on for their livelihood, but to think about how we can make them safer; how we can preserve workers’ earnings, even if there is an extreme heat event,” says Dahl. The report found that outdoor workers may collectively lose $55.4 billion in earnings a year by the middle of the century.

Addressing climate change is the main solution. With action now to reduce emissions, the number of outdoor workers affected by unsafe heat at least seven days a year would drop from 18 million to 14 million. If the world hits net zero by 2050, the global temperature will eventually stabilize, and extreme heat days are expected to drop.

Recognize your company's culture of innovation by applying to this year's Best Workplaces for Innovators Awards before the extended deadline, April 12.