The chocolate industry has problems. Twenty years after promising to phase out the “worst forms” of child labor on cocoa plantations, chocolate brands still haven’t succeeded. In Ivory Coast, where a third of the world’s cocoa is grown, rainforests are plowed down for cocoa plantations; in the last 50 years, the country has lost more than 80% of its forests, mainly to cocoa production. By some estimates, the carbon footprint of chocolate isn’t far behind meat and dairy, making it worse for the climate than most foods. Climate change is also making cocoa harder to grow.

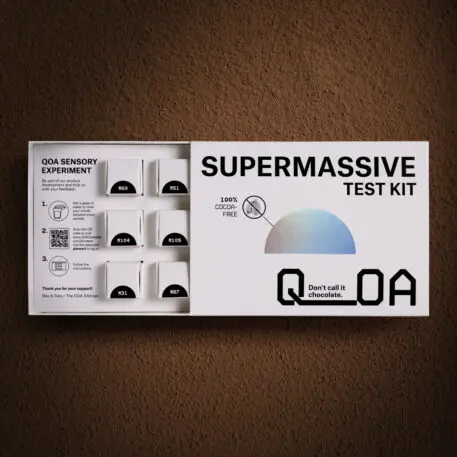

But what if a chocolate bar could be made from other plants instead? QOA, a Germany-based startup now part of the tech accelerator Y Combinator, makes cocoa-free chocolate using “precision fermentation” of other ingredients. Over a little more than a decade, the company hopes to fully replace the cocoa used in mass-market products.

Cofounder Sara Marquart, a food scientist who previously worked at another startup creating coffee-free coffee, began working on the project earlier this year with her brother, an entrepreneur who wanted to find more meaningful work than his previous consulting firm. “We started making chocolate in my brother’s kitchen,” she says. “We bought seven Thermomixes and set them up on my brother’s table.”

Along with a tiny team of scientists, she started analyzing the flavor of cocoa. “Pretty much every food has a fingerprint, like a human has a fingerprint, right? It’s very unique,” she says. “We analyze the fingerprint of raw cocoa, fermented cocoa, roasted cocoa, to understand what is making cocoa this unique little bean that has so much flavor?” Then they did the same analysis of byproducts from food production, such as the residues left after pressing sunflower seeds to make oil. By fermenting a handful of these ingredients, they were able to “extract the building blocks of the flavor,” she says. “And then we reassemble that in a big brewing tank. You can think of it like beer brewing, in a way.” After fermentation, the final product can be roasted and dried like conventional cocoa.

The flavor took time to get right. In taste tests of an early version, the sample chocolate got low scores, with an average rating of 4.9 out of 10. “One of the people commented that she had to brush her teeth three times,” Marquart says. But as the team reworked the formula and sent new samples out to the same random group of testers, the ratings doubled. The team then went to chocolate sensory experts at a research organization called Fraunhofer, who said that they couldn’t distinguish between the startup’s version of chocolate and conventional chocolate. “Then we were like, okay, now we’re ready to launch,” she says.

They’ve now started talking with major chocolate brands. “The best feedback that we got is that from a person who was super skeptical, like, ‘Yeah, you can never never do that,’ when we first talked to him,” she says. “And then he tastes it and he wrote us an email the next morning saying, ‘Hey, guys, how can we collaborate?”

The startup plans to also launch its own brand to help make more people aware of issues like child slavery in cocoa production. (In a common case, children living in Mali might be recruited for work and told they’ll be well paid, and then trafficked across the border to Ivory Coast, where they’re forced to work without pay for years, and isolated from other child workers.) “I think only a few know about the child labor, and even less know about the climate impact,” she says. They’re working with a Michelin-starred chef, for example, to showcase how the chocolate can be used. But the primary goal is to replace the cocoa in mass-market candy and other chocolate products. Pilot tests with bigger brands are likely to begin next year.

By using byproducts as ingredients, QOA can shrink the carbon footprint of chocolate. But produced at scale, the cocoa replacement can also be less expensive that the real thing. The intent isn’t to replace sustainably-produced single-origin chocolate. “We love chocolate, we love cocoa, and we love the product that is produced in a sustainable and just way by small-stake farmers,” says Marquart. “The only problem is that it’s not a scalable approach to make chocolate for the global consumption of chocolate. We’re just wanting to offer a solution for mass market chocolate that we can skip the CO2 footprint and the child slavery.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.