Look at your feet. (I’m going to assume you’re wearing shoes.) Do you have any idea how good or bad those shoes are for the environment? Or did you pick them for their color, comfort, or style?

The truth is, beyond obviously terrible choices, such as single-use plastic bags, most of us have no clue how good or bad most products are for the environment, and with few exceptions, there’s no easy way to find out.

A new startup out of France called Carbonfact wants to change this by building a one-stop website where you can look up the carbon impact of any product. For its launch, the company is starting small, by allowing you to look up the carbon impact of your sneakers, ranging from icons like Nike Air Force 1s to many boutique-branded shoes out of France and Spain.

“Our vision here is that CO2 will be super, super important for every retailer … and brands and marketplaces will need a technological player to display the carbon footprints massively on a large number of products,” says cofounder and CEO Marc Laurent. “They won’t be able to do it by themselves, because you want an impartial judge and trusted third party to conduct the analysis.”

Carbonfact is starting with shoes because their carbon footprint is relatively easy to measure (a mixture of the core components in the products being limited by design and using materials that are well understood, thanks to corporate disclosures). In 2019 alone, 24.3 billion pairs of shoes were produced, with an estimated carbon footprint of 700 million tons of CO2—which Laurent readily points out is equivalent to the CO2 output of the entire country of Germany.

Carbonfact begins by estimating the footprints of various sneakers, using open source models developed by institutions like MIT. It cross-references these models against the environmental reports put out by major companies to build a single number.

“What we do here is parse the internet, especially their product pages and sustainability reports, which are tens of pages of PDFs no one reads,” explains Laurent. “But we deep dive into those docs, find the country of manufacturing, the materials they used, and we try to gather all this data.”

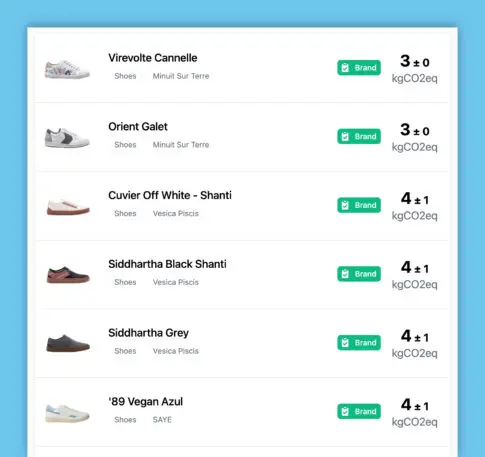

On the site, Carbonfact currently lists about a dozen shoes, each with its carbon cost. The worst listed shoe is the Nike Tanjun, costing an estimated 32kg of CO2, thanks largely to its use of nylon. Its best listed shoe is the Virevolte Cannelle, a riff on the Stan Smith by the vegan shoe brand Minuit Sur Terre. As they are educated guesses without perfect insight into the specifics of materiality, manufacturing, and distribution, Carbonfact discloses its full calculations, and that its figures can be off by about 20%.

In more ideal circumstances, Carbonfact doesn’t want to guesstimate. It is hoping that companies will step forward and share their own internal carbon analyses. Just a week into its first launch, that’s already happening. Twelve brands—mostly boutique sneaker brands out of Europe—have already shared their data. But the site is still lacking data from shoe giants like Nike and Adidas, so those products are estimates.

There’s growing precedent for these product-by-product carbon disclosures. Allbirds discloses the carbon imprint of its products, and recently teamed up with Adidas to build the lowest carbon-performance sneaker ever made (the carbon impact is Sharpied right on the shoe). Meanwhile, the tech-hardware company Logitech and the vegetarian-meat company Quorn have both started sharing the carbon imprint of their products right on the packaging.

Carbonfact wants to facilitate such disclosures, and make them easy for the public to look up. To generate revenue, Laurent insists that it will never charge companies to take part and share their data because that’s antithetical to the mission, creating another hurdle to companies disclosing the carbon cost of their products.

Instead, Laurent imagines that the business could charge major retailers, like Zappos, to provide carbon data on shoe listings. It could also sell some of this data back to companies that are trying to assess their own carbon footprint relative to competitors.

It’s a tenuous business plan that Carbonfact is still working out, Laurent admits. And in the more immediate future, Carbonfact has an even larger challenge ahead. Right now, the company lists the carbon footprint of products in kilogram weight. (Their current listings range from 4kg to 32kg.) Many companies take this approach with carbon disclosures, and yet, these numbers don’t really make sense to anyone but the experts. And the way I find myself deciding if a shoe is good or bad on their list is only by comparing its carbon number to others.

These figures have no intrinsic meaning to consumers. They are not like the FDA label, on which weight measurements for vitamins and fat are contextualized with an overall percentage of what you should consume. Carbonfact’s figures are clearly legible but largely meaningless.

Laurent knows this approach “isn’t sufficient,” and these numbers will only get more confusing as the company includes more product categories (imagine comparing a car to a refrigerator to a shoe!). One solution the company plans to implement is to highlight best-in-class products with explanations like, “the average pair of shoes costs 14kg of CO2; this shoe with a 5kg CO2 carbon footprint is in the best 5%.”

Carbonfact is a big idea that’s being launched by a mere three-person team (with funding they are not disclosing). It’s hard to imagine the company succeeding even with limitless resources, especially since many industries are only beginning to audit the true lifecycle carbon costs of their own products. Furthermore, as Carbonfact can probably only scale with disclosures coming from companies, it won’t be so much of a third party auditor as a depository for information. As we saw with VW’s diesel scandal, companies lie about their environmental impact.

And yet, something like Carbonfact needs to exist. Consumers deserve to be able to look up the environmental cost of their products with ease and transparency, and with standards (a la our FDA labels) that they can understand. We already have a bit of this with Energystar ratings on appliances and EPA gas mileage estimates on new vehicles. Now, we just need it for every single other thing that we might buy in the world.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.