Since the modern Olympic Games began 125 years ago, they’ve never been just a sporting event. They’re a pageant the entire world tunes into, full of parades, music, even costumes.

The outfits that Olympians have worn over the years tell a story about the broader sociopolitical dynamics of their time. They also reveal a darker side of the Olympics, with classism, racism, and sexism just below the surface. David Goldblatt, author of The Games: A Global History of the Olympics, says it’s important to go back to the origins of the Games to fully understand the ethos of the event.

In the decades that followed, the Olympic Games became a global, institutionalized event that tried to keep up with the rapid social change of the 20th century, allowing women to participate in 1900 and then expanding beyond Western nations in 1924. But at every turn, the International Olympics Committee created barriers that made it hard for these new athletes to participate. “People of color, women, and people from lower-class backgrounds were absolutely not part of the model,” Goldblatt says.

One way to trace this history is by observing the clothes that Olympians have worn over the last century. Here are key moments in Olympic history and what they say about the culture of the Games.

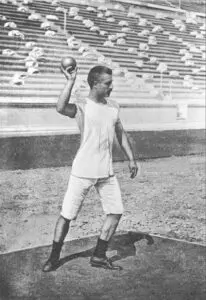

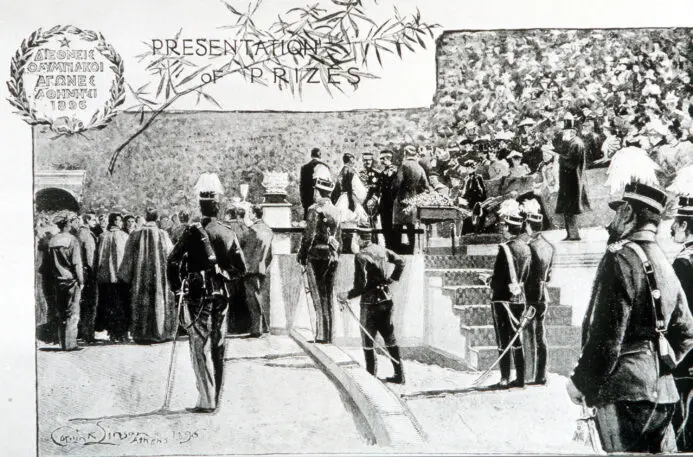

The gentleman athlete

At the very first medal ceremony in 1896, winners wore coats and tails to receive their awards, revealing that the Games were very much designed for the upper-class men of Europe who asserted their social standing through this formal dress. “Sports were designed to generate the Christian muscular gentleman who would go on to be the Viceroy of Mumbai or the Governor of the Caribbean,” Goldblatt says.

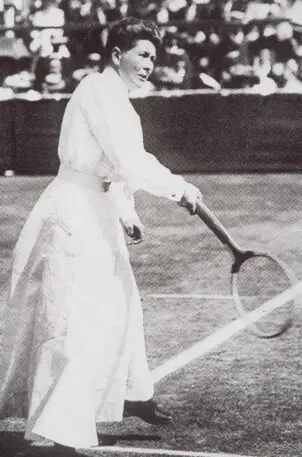

Playing in petticoats

Women were allowed to compete for the first time in 1900. Of the 997 athletes present, 22 women competed across five sports: tennis, sailing, croquet, golf, and horseback riding. Women had been lobbying to participate for years and organized their own competing sporting events, which prompted the Olympic Committee to let them in. But from the start, there was resistance. “You could see in the personal correspondence among the organizers of the Olympics that they were revolted by the presence of women, even though they had to give in and allow them to participate,” Goldblatt says.

One concern was that the women would be a distraction to the men, who would see their bodies in action. In response, the Olympic Committee forced women to wear modest clothes that often made it hard for them to compete comfortably. “The outfits that women were being asked to wear to play tennis or to cycle or swim in were ludicrous,” he says. “There was a real fight from feminists in the years that followed about what women would be allowed to wear.”

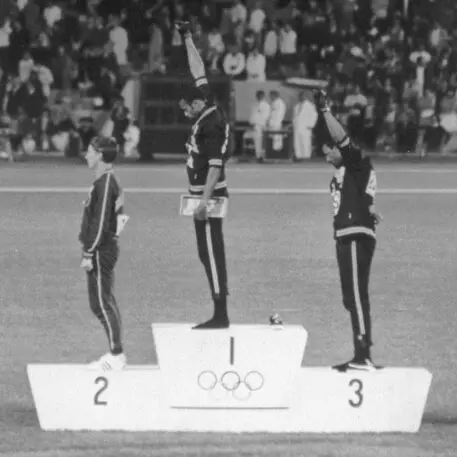

Black gloves and no shoes

The 1968 Olympics took place in Mexico City at the height of the civil rights movement in the United States, and Black athletes made sartorial choices at the Games to signal their political beliefs. American sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos, for instance, won the gold and bronze medals, respectively, and attended the medal ceremony wearing black socks and no shoes as a way to draw attention to the poverty of Black people in their home country. They also wore black gloves, and each raised a fist in the air during the playing of the U.S. national anthem. Peter Norman, an Australian sprinter, won the silver medal and chose to support Smith and Carlos’ protest by wearing a badge of the Olympic Project for Human Rights.

Military vs. stewardess outfits

Even today, many countries design opening ceremony outfits that look like military uniforms. This has been true from the earliest days of the Olympics. According to Goldblatt, for decades, Olympic teams from around the world were often drawn from members of the armed forces. “Soldiers had a real advantage,” he says. “Who else had time to practice to compete, without getting any compensation? So the men were often in these absurd blazers and hats, marching like they would in the army.” Of course, this created all kinds of strange dynamics: These athlete-soldiers may have been at war with other countries represented at the Games.

And in a sign of the gender dynamics of the 20th century, the women’s opening ceremony outfits often looked very similar to airline stewardess outfits throughout the ’60s and ’70s. So while the men’s outfits were martial, the women’s outfits made them look like they were in a subservient role. Women fought hard to participate in more and more events, but each victory was hard-won. It wasn’t until 1984 that women were allowed to run the Olympic marathon. “Women had to prove, over and over, that they were strong enough to compete in each event,” Goldblatt says.

The corporate takeover

In the 1960s, Adidas and Puma began to grow as sports brands. The two companies competed to get the German sprinter Armin Hary to run in their shoes for the 1960 games; but at the time, brands weren’t allowed to pay athletes to represent them. Hary eventually won the 100-meter dash in Puma shoes and, while there were rumors that he received cash payments from the brand, there was no evidence to support the claim.

But in the years that followed, sports brands transformed what athletes wore to compete in the Olympic Games: They started wearing high-tech sneakers and outfits made from materials better suited to physical activity. In 1968, Adidas set up a stall in the Olympic Village in Mexico City where it gave away free gear to athletes. “It was incredible advertising,” Goldblatt says. “That was the moment the three lines of the Adidas logo were imprinted in people’s minds.”

By the 1980s, the International Olympics Committee allowed athletes to accept sponsorships from brands, and in 1985, it launched a program that allowed companies to sponsor the event as a whole, which meant their logos would be prominently featured in stadiums. Some have argued that these corporate sponsors have ruined the Games by making them overly commercial, transforming sports from an emotionally-satisfying activity that brings people together into a money-making endeavor.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.