Fashion companies keep trying to convince us that their business models are sustainable. From clothing rental platforms like Rent the Runway to resale sites like ThredUp to brands like Everlane that use recycled plastic. But until now, there’s been very little data about whether these approaches are actually better for the planet.

In Finland, a team of researchers wants to clear things up. In a recent study published in the journal Environmental Research Letters, they calculate the greenhouse gas emissions connected to five different ways of owning and disposing of clothing, including resale, recycling, and renting. Their findings were disturbing. Renting clothes had the highest climate impact of all—even higher than just throwing them away. And recycling also had a high climate impact, because industrial recycling processes generate a lot of emissions.

Ultimately, the researchers determined that the most sustainable way to consume fashion is to buy fewer items and wear them as long as possible. If there’s more life in the clothes, you should resell them. But ultimately, the new business models like recycling and renting, which are frequently touted as eco-friendly, actually aren’t as sustainable as we’re led to think. “We’re by no means discouraging brands from developing recycling technology,” says Anna Härri, a coauthor of the paper and a graduate student in the department of sustainability science at LUT University. “But it’s important to realize that recycling and rental generate significantly more emissions than resale or simply wearing your clothes longer. This should inform how the fashion industry evaluates how to be more sustainable going forward.”

The mirage of the circular economy

In the study, the researchers note that the “circular economy” has been a buzzy phrase in the fashion industry, thanks to organizations like the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, which have championed it. But many brands often misuse it to give themselves a halo of sustainability, without fully embracing the concept.

A circular system is the opposite of our current linear system of buying clothes, wearing them, and then getting rid of them. Instead, it involves keeping clothes circulating in the economy for longer by wearing them for longer and then passing them onto another consumer. Then, at the end of a garment’s life, the clothes are recycled to make new clothes, which would mean fashion brands don’t need to extract new resources to create new garments.

Many experts and activists believe that the circular economy could help the fashion industry become more sustainable. The problem is that many brands have co-opted one small aspect of the circular system—like using some recycled materials or renting clothes to keep them on the market longer—and then marketing their entire company as sustainable.

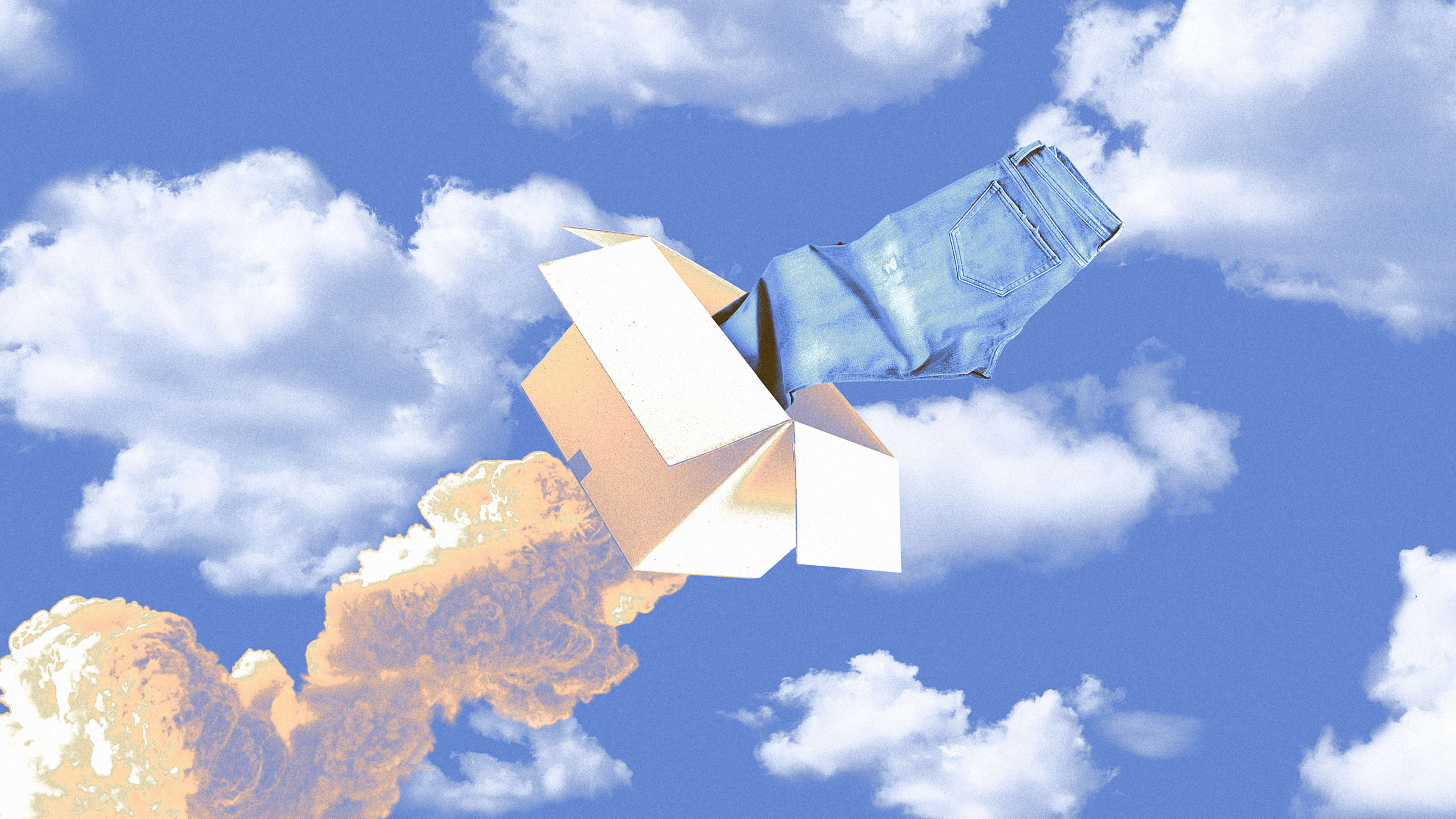

This study was designed to test these claims. The researchers compared five different approaches to owning and disposing of a pair of jeans: Wearing them and then throwing them away; wearing them for longer than average before throwing them away; reselling them; recycling them; and renting them. In each scenario, they calculated the “global warming potential,” which refers to how greenhouse gases are emitted throughout the lifecycle of the jeans. They considered everything from manufacturing and transportation to washing and disposing of them.

In the end, the data was clear. Renting generated the highest amount of emissions because of all the transportation involved; indeed, the study found that it’s actually better, from a climate perspective, to simply buy the jeans, wear them, and throw them away. And while the report didn’t specifically look at the lifecycle of donated clothing, here too it’s worth taking a closer look at your practices. A recent book by Maxine Bédat noted that many of Americans’ donated garments end up in African landfills.

The problems with renting and recycling

One important takeaway is that recycling should be considered the last-case scenario for a garment, once it has been worn hundreds of times and is no longer fit to wear. It should not be treated as a guilt-free way to wear clothes a few times and dispose of them. “Recycling is an important part of a sustainable future,” Härri says. “We encourage companies to keep investing in it. But it cannot replace reducing consumption.”

Härri says that the benefits of recycling depend on the material you’re recycling in the first place. The calculations in this study were based on a pair of jeans that were largely made of cotton. Growing cotton doesn’t produce a lot of emissions, so recycling cotton may actually have a higher climate impact than simply harvesting cotton. However, synthetic fibers—like nylon and polyester—are made from oil and require a lot of emissions to produce. So it might make more sense to recycle these fabrics rather than extracting oil to create them from scratch.

The other big takeaway is that clothing rentals–as they exist today–just aren’t sustainable, largely because of the transportation required to send them back and forth between customers’ homes and the warehouse. The report does say that if rental companies drastically change their logistics to make them more climate friendly, such as, say, only using modes of transport that have zero-emissions or low-emissions, then renting would become on par with reselling, form a climate perspective. But most rental companies today, particularly those in the United States, are not doing this.

The main problem, Härri notes, is that rentals are premised on the idea of cycling through trends quickly. And no matter how you try to keep up with trends, either by buying fast fashion or renting, the outcome is never sustainable. “Buying fewer clothes and wearing them repeatedly is really the opposite of fast fashion,” she says. “For the fashion industry to become more sustainable, both consumers and brands need to move away from the entire concept of fast fashion.”

Note: This story was updated to include Rent the Runway’s study.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.