A new search engine? One that people have to pay to use?

At first blush, it may seem like a textbook example of a startup idea destined never to get anywhere. By definition, any new search engine competes with Google, whose 90 percent-plus market share leaves little oxygen for other players. And we’ve been accustomed to getting our search for free since well before there was a Google—which might make paying for it sound like being expected to purchase a phone book.

But Neeva is indeed a new search engine, officially launching today, that carries a subscription fee. Though it’s extremely similar to Google in many respects—with a few twists of its own—it dumps the web giant’s venerable ad-based business model in the interest of avoiding distractions, privacy quandaries, and other compromises. It’s free for three months—long enough for users to grow accustomed to it without obligation—and $4.95 a month thereafter. Apps for iPhones and iPads, and browser extensions for Chrome, Firefox, Safari, Edge, and Brave, are part of the deal.

Neeva may have a certain whiff of improbability about it, but its cofounders, Sridhar Ramaswamy and Vivek Raghunathan, are the furthest thing from naïfs. Two long-time Google executives with more than a quarter-century of experience at the web giant between them, they have an insider’s understanding of how it operates. Moreover, about 30 percent of the roughly 60-person staff they’ve assembled at Neeva consists of ex-Googlers, including Hall-of-Famers such as Udi Manber (a former head of Google search) and Darin Fisher (one of the inventors of Chrome). They’ve also secured $77.5 million in funding, including investments from venture-capital titans Greylock and Sequoia.

Whatever the answer to that question, Neeva’s creators understand what they’re getting into. “Sridhar and Vivek, with their depth of knowledge on everything from technology to what people actually need and do, are probably the only people in the world where I would go, ‘Okay, I’ll go on this journey with you, because you know how to go on this journey,'” says Greylock partner and LinkedIn cofounder Reid Hoffman.

(Which is not to say there aren’t other ambitious privacy-centric search engines on journeys at least somewhat similar to Neeva’s. DuckDuckGo has been on its own for 13 years; once a one-man operation, it now has 129 employees and $100 million in annual revenue from ads that don’t involve tracking individual users. And Brave, the browser company founded by web pioneer Brendan Eich, is beta-testing its own privacy-first search engine and says free and for-pay versions will be available.)

Looming antitrust case aside, it’s not that Google is all that obviously vulnerable. Over the years, unlike some products with monopolistic market share—Microsoft’s Internet Explorer comes to mind—the search behemoth hasn’t calcified through lack of competition. Instead, it remains the category’s leading engine of innovation: Google says that it rolled out 4,500 improvements last year alone.

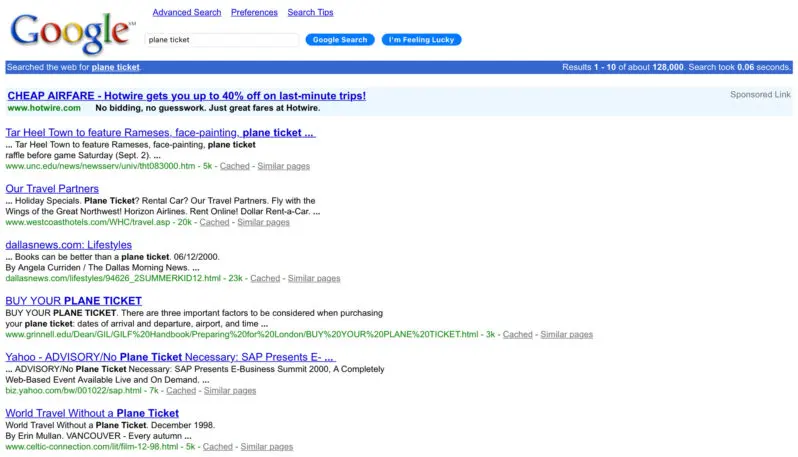

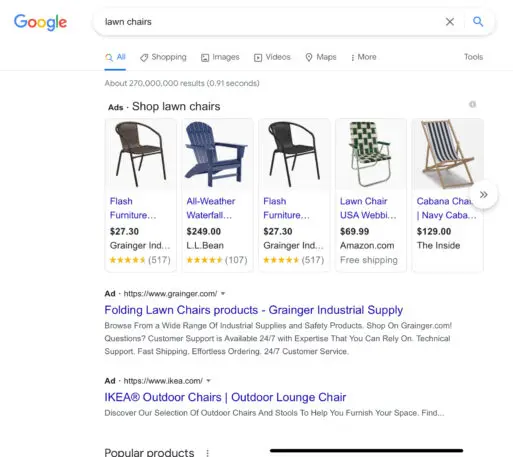

But some of the downsides of Google’s dependence on ad revenues are right before our eyes. Once famously unobtrusive, the ads displayed with search results have gradually migrated from the right column to the top of search results, multiplied in number and size, and lost the shaded box that isolated them from organic results. Today, for many searches, ads all but crowd the organic results off the screen until you scroll downwards. For others, links to Google’s own money-making services, such as Google Flights, get prime real estate.

Then there’s the fact that Google builds profiles of its users based on their online activity, the better to precisely target them with advertising not only at its own sites but all the other ones across the web whose ads are powered by Google. With no ads to serve up, Neeva shouldn’t leave privacy-conscious types feeling like they’re being monitored for ulterior purposes. (By default, Neeva does hold onto your searches for 90 days to improve the quality of features such as autosuggestions, but you can erase this log or tell the service you don’t want it to keep it in the first place.)

In another break from search-engine tradition, Neeva says that it will turn at least 20 percent of its top-line revenue over to publishing partners, including the first two it’s announced, Quora and Medium. Though the details of where this could lead remain vague, it’s another attempt to set Neeva apart from Google, which has often been accused of benefiting from media outlets’ content without adequate compensation, a long-simmering dispute that has led to lawsuits and legislation. (After years of controversy, Google can at least point to the fact that it’s spending $1 billion on programs involving giving money to news outlets.)

Ramaswamy and Raghunathan tend to frame their discomfort about Google’s business model in polite terms. One of Neeva’s investors—NYU professor, author, and entrepreneur Scott Galloway—isn’t so circumspect. As you might expect of someone who has called for the breakup of Google and other tech giants, he’s withering in his analysis of Google and enthusiastic about the possibility of an upstart like Neeva chipping away at its pervasiveness.

Neeva investor Scott GallowayThe thing that gives you cancer, the tobacco, if you will, is the ad model.”

Galloway emphasizes that he put money into Neeva mostly because he thinks it’s a smart investment. At the same time, he adds, “I want to be a small part of the effort to try and release the stranglehold that Google has on content discovery. I think it leads to very bad places.”

Even if you’re nowhere near as agitated over Google’s dominance and practices as Galloway is, you might find yourself rooting for what Neeva is trying to accomplish. Search “is a phenomenal daily habit that has transformed how we live,” says Neeva board member Margo Georgiadis, herself a former high-ranking Googler who ran the company’s commercial and ad operations in the U.S., Canada, and Latin America. “But there’s an opportunity with how we’ve evolved the way we live our lives and use technology to make it much, much better if your business model is aligned 100 percent with the consumer.”

It’s hard to bring up ad-subsidized services from big tech companies without someone helpfully reminding you that if you’re not paying for the product, you are the product. With Neeva’s subscription-based model, the product is unquestionably the product. It just needs to be a compelling one—even though its team is small and the competition has a 23-year head start.

‘A clean start was what I needed’

In a way, the Neeva story begins in 2003. That’s when Ramaswamy joined Google and was put to work on its still-nascent advertising team. Placing targeted text ads next to search results was already proving to be a powerful idea, but “little did I, or most others, realize that this would be one of the largest businesses ever,” he remembers. He devoted the next fifteen years to the engineering side of that growth, eventually overseeing 10,000 Googlers as senior VP of ads and commerce.

But by the latter part of that time, he was developing qualms about the whole proposition of monetizing eyeballs through targeted ads all around the web, as Google was doing. “One of the things that I paid a lot of attention to is how data was separated between off-Google experiences and on-Google experiences,” he explains. “To me, keeping that data separate was an important part of the promise that Google implicitly made to its users.” Increasingly, however, he found himself having to consent to compromises such as users’ Google searches influencing the ads they saw on YouTube.

“We tried to be thoughtful about how information flowed around, but it was also very clear where things were pointed at,” Ramaswamy says. Having had his fill of the dilemmas associated with the ad business, he explored the possibility of pivoting to a different role within Google. Ultimately, “I decided that a clean start was what I needed,’ he says.

After quitting Google in the fall of 2018, he thought he’d found that clean start as a venture capitalist at Greylock. The conflict between ad-based business models and serving users remained on his mind, though. Thinking about it took him down the path that would lead to Neeva.

Like Ramaswamy, Raghunathan wrestled with the effect that business pressures had on user experiences. Marketers love to reinforce their messaging by exposing consumers to the same ad over and over and over. YouTube fans rankle at such repetition. Guess whose interests won out? “We’d have these well-intentioned conversations around trading off users’ happiness for customer value,” Raghunathan recounts.

Still at Google, Raghunathan chatted with Ramaswamy about the startup idea the latter was formulating. “I remember him telling me this insight, this string he was pulling on,” says Raghunathan. “That you could not reimagine search the product without reimagining the business model that underpins search.” Eager to join that effort, Raghunathan left Google after almost 12 years to become Neeva’s cofounder.

(Why the name “Neeva?” Raghunathan cheerfully admits that they chose it, then backfilled in a rationale: “In hindsight, there is a story we can tell about Neeva, in Sanskrit, meaning ‘fundamentals’ or ‘the basics.’ It actually means something that is very core to our mission. But I’d be lying if I told you we knew that.”)

For Udi Manber, what Neeva was up to was compelling enough to lure him back into search, an area he’d left behind in 2015 to focus on health-related technologies at the National Institutes of Health and elsewhere. Earlier this year, he joined Neeva part-time, spending two or three days a week on research efforts.

A legendary computer scientist who held top jobs at Yahoo and Amazon as well as Google, Manber was another key Googler who had his frustrations with the dynamics of ad-subsidized search. “I was one of the biggest advocates of privacy at Google, and I pushed for it a long time,” he says. “I won some fights. I lost many others.” The fact that Neeva is tiny is liberating, he argues: “Innovation is hard for every company, but I think small companies are better at it than large companies overall.”

‘A weird tight rope’

To say that Neeva is in a position to rethink search is not to suggest that it’s trying to change everything. What it’s launching is not the iPhone to Google’s BlackBerry. Indeed, much of the user experience can fairly be described as “Google-like.”

That’s not a bad thing. “The paradox and the challenge here is that it has to be different enough from what already exists to get attention and to be engaging, but not so radically different that it’s disorienting to people,” says Greg Sterling, a long-time observer of the search business and VP of market insights at location marketing company Uberall. “There’s a weird tight rope that I think they’re trying to walk.”

Vivek Raghunathan, NeevaWherever we can build, we will build. Where we can license or buy, we will.”

“Wherever we can build, we will build,” declares Raghunathan. “Where we can license or buy, we will. Users don’t care. And so we will do what makes sense for users to build a maximally differentiated, maximally useful, maximally, delightful product.”

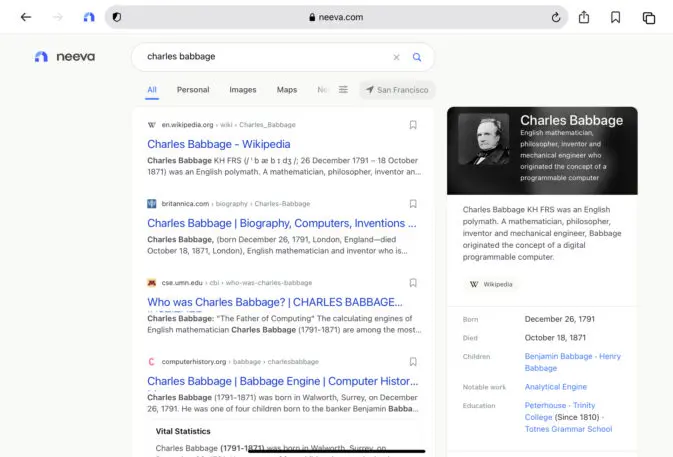

Nothing about the end result is likely to discombobulate the Googling masses. There’s a search field that looks just like Google’s search field—except that it sports a rotating set of taglines such as “No ads here” and “You are not the product.” There are autosuggestions as you type, plus links to related searches and “People Also Asked” queries. Rows of videos and news items are interspersed throughout the results, and the right column often includes a block of facts on whatever you searched for based on sources such as Wikipedia.

Dig into the same results on Neeva and Google, however, and you’ll notice some differences. For instance, while both search engines respond to searches such as “best laptops” with tidy carousels summarizing expert reviews, they’re more prominent on Neeva, while Google puts a similar-looking carousel of paid links at the top. You can also expand Neeva’s summaries into more detailed previews without leaving the search results, a boon for comparison shopping. (The service takes a similar approach with recipes.)

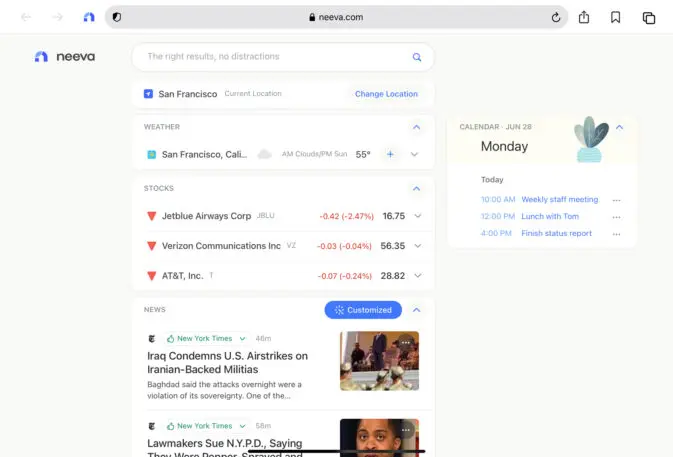

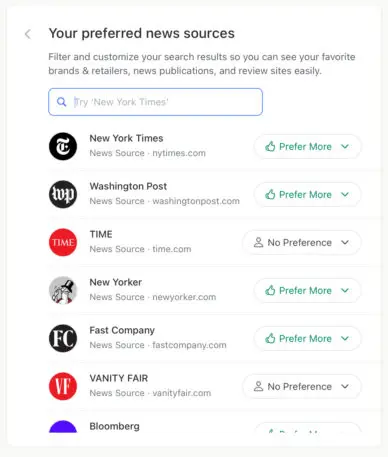

The Google home page consists of a search field, “Google Search” and “I’m Feeling Lucky” buttons, and an expanse of white space—remarkably unchanged from its original look back in 1998. Neeva, by contrast, fills its home page with personalizable widgets. They include ones for local weather, stock prices of your choice, and news. That last widget consists entirely of stories from name-brand media outlets—from The Daily Beast to Fox News—and you can customize it by specifying which sources you want to see more often or less often.

Still another distinguishing characteristic is Neeva’s integrations with third-party services. You can hook the service up with information sources such as your Gmail or Outlook email and calendar, Google Drive or Dropbox storage, and/or Slack or Jira account. Neeva will then index them and intersperse material from them in your search results as well as presenting it in a dedicated “Personal” tab. Google has experimented with similar concepts in the past—it once mashed up Google search and Gmail—but seems to have moved on from the concept.

For all that’s nice about Neeva—starting with its organic results sitting at the top of the page rather than below a payload of advertising—it hasn’t done the impossible by reaching Google-like sophistication right out of the gate. Those product-oriented results for searches such as “best laptops” are well packaged, but the ones I checked out were thin on sources, with PCMag dominating the review links to such an extent that I wondered if it was through some partnership deal. (It isn’t.)

Neeva also doesn’t do local information anywhere near as well as Google: It knows my Zip Code, but when I searched for a local pizza chain, it gave me a map for the branch 28 miles away, not the one within walking distance. It can answer questions such as “What time is it in Rio?” and “How tall is Joe Biden?” with facts that appear on the results page itself, but it doesn’t do so for as dizzying an array of queries as Google does. When I used the pre-release site, I also encountered the occasional out-and-out glitch, like a thumbnail map of San Francisco that turned into Indianapolis when I clicked on it.

Ramaswamy acknowledges that in its current state, Neeva is something of a rough draft: “We have several large launches planned for next month, on the search quality side, after being publicly available,” he says. It will be interesting to see where it gets by the fall, when the people now signing up conclude their three-month free trials and choose whether to become paying customers.

Where it could go after that is hard to say, but it’s not like search has no remaining problems to solve. When I asked Manber about what he was working on, he wouldn’t tell me: “I learned a long time ago to talk about things only after I’ve done them, not when I’m just planning to do them.”

‘The browser and search are just so intertwined’

As I began working on this article and got pre-release access to Neeva, I wanted to use it all the time. To ensure that I didn’t reflexively Google for anything, I went into Safari’s settings to change my default search engine to Neeva. It was only then that I realized I couldn’t. Most major browsers make you pick from a few pre-selected search engines, not (yet) including Neeva; only Chrome allows you to choose one that’s not on its canned list.

That experience underlined that Neeva is entering a world that isn’t exactly wired to give a new stand-alone search engine its best shot at success. To control its destiny, a search company really needs to write at least some of its own software; it’s not a coincidence that everyone from Google to DuckDuckGo has come out with a browser. And now so has Neeva, with its iPhone and iPadOS browsers as well as extensions that embed similar functionality in other browsers.

According to Fisher, the symbiotic nature of browsing and searching can create design conundrums that put a browser/search engine company at odds with its users. For example, if you type the name of a site into the browser’s address bar, will it send you right there? Or will it err on the side of directing you to a page of search results it can monetize through ads?

With no ads, Neeva can resist such temptations. “When I think about Neeva and that simple business model that it has—if people are happy, they’re paying—it opens the door to not having that tension,” says Fisher.

Sridhar Ramaswamy, NeevaFor us, it is an ethical issue: I don’t want to disrupt other people’s ability to monetize.”

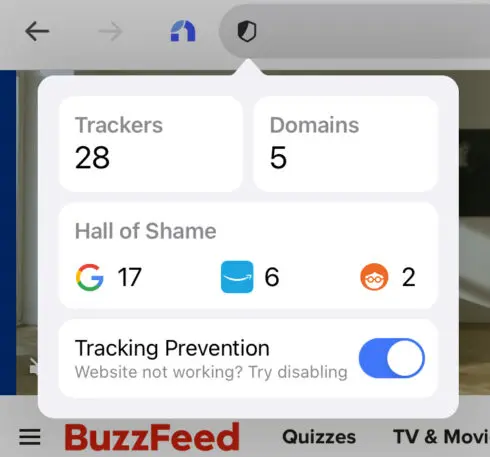

A few days before Neeva’s official debut, as I used the pre-release browser, I found that it not only foiled trackers but also eliminated advertisements all over the web. It turned out that Neeva was also surprised by the sweeping ad deletion, an artifact of its browser’s reliance on core technologies from Mozilla’s Firefox. The Mozilla anti-tracking system nuked ads in a way that Neeva wasn’t comfortable with—especially given its goal of being a friend to web publishers—and so it subsequently dialed back its aggressiveness.

“For us, it is an ethical issue: I don’t want to disrupt other people’s ability to monetize,” says Ramaswamy. “It is hard enough being a quality content creator.”

‘If we’re not good at it, we shut down’

For Neeva, floating a little under the radar rather than immediately capturing the web’s imagination might have its advantages: In the past, numerous search-engine startups were hailed as Google killers, and the heightened expectations consistently became an albatross. Cuil turned out to be terrible. Powerset was acquired by Microsoft and folded into what later became Bing. WolframAlpha is still with us—and still quite useful—but rather than killing Google, it seems to have presaged some of its new ideas.

All that happened long enough ago that it may not tell us much about Neeva’s prospects. And if nothing else, the old conventional wisdom that nobody is willing to pay for anything on the internet is definitively dead. More than 200 million people pay for Netflix. One hundred fifty-eight million pay for Spotify. Almost 7 million pay for digital access to The New York Times; 700,000 pay for Medium. That’s despite the fact that all of these services have plenty of free competition. “Consumers are increasingly demonstrating the willingness to pay for relevant, more personalized experiences in their lives, and they do it across most areas of their lives,” says Neeva board member Georgiadis, a former CEO of Ancestry, whose 3 million customers who pay $99 a year and up for its genealogy service.

In the end, Neeva’s aspirations don’t sound wholly fanciful. Even if it convinces only one or two percent of search-engine users to pay, Ramaswamy believes that it will punch above its weight. “Subscription companies are valued at a multiple of revenue, while ad-supported companies are valued at a multiple of EBITDA,” he says. In other words, each paying customer adds more to Neeva’s valuation than a whole bunch of people looking at ads does to Google’s.

The refreshing simplicity of Neeva’s business model is one of the things that has drawn so much top talent to the startup. Engineer Asim Shankar—yet another former Googler—describes it as “We provide a service, and if we’re good at it, we get paid for it. If we’re not good at it, we shut down.” Now it’s time to see if that also makes sense to the web searchers who will ultimately get to decide just how good Neeva is.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.